Can you teach empathy?

Scientists using a new combination of brain scans and old-fashioned biofeedback techniques say they helped people focus and boost their feelings of affection and empathy.

They hope to finesse their approach into a way to help treat people with mental illnesses such as postpartum depression, and say it might even be used to help some people ranging from those with mild autism to outright psychopaths.

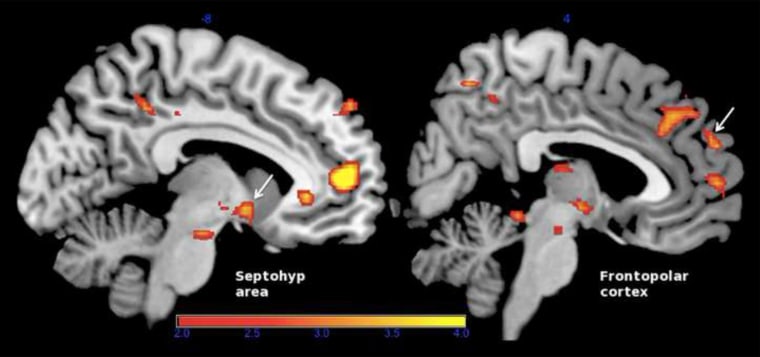

And they say theirs is the first study to map the complex emotions associated with empathy in the brain.

“We were interested in emotions that drive us to do altruistic acts, to try to correct our mistakes, to try to be better people."

“Other groups have been mapping single brain regions related to emotions, but to map complex emotions such as empathy, it is important to look at several parts of the brain at the same time,” said Jorge Moll of the Cognitive and Behavioral Neuroscience Unit at D’Or Institute for Research and Education (IDOR) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

“We were interested in emotions that drive us to do altruistic acts, to try to correct our mistakes, to try to be better people,” he told NBC News. “We wanted not only to map these emotions, but to allow people to train these emotions.”

The idea isn’t completely new.

“In ‘Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?’ Philip Dick’s 1968 novel and later in Ridley Scott’s film ‘Blade Runner,’ societal cohesion depended on the ‘empathy box,’” Moll’s team writes. “Although prospects of such a device remain in the realm of science fiction, recent advances in neuroscience and computer science have opened a window towards this possibility.”

It took a while to “train” the computer to recognize the brain patterns associated with general feelings of tenderness. They did it by getting people to sit in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scanner, which measures real-time brain activity, and then asking them to think about tender moments.

“You ask them to go back in their lives and identify moments that were very important for them in which they felt feelings of empathy and tenderness,” said Moll. He tried it himself, thinking about a time when he hugged his children. The feelings were so overwhelming, he said, that it was hard to distract himself.

People were also asked to think about times when they felt pride in something they did, and to think neutral thoughts, also, such as remembering a recent trip grocery-shopping.

“We wanted to measure very specific brain patterns,” Moll said. The computer program compared the brain activity of the three emotional states to map out patterns specific to tender, empathetic thoughts.

“You could use it to reduce unwanted feelings.”

Next, 25 volunteers were asked to try to control these thoughts and feelings. For the experiment, Moll’s team devised a ring-like image that would become more focused the more a volunteer’s brain patterns fit the template of empathetic feelings.

As a control, some of the volunteers were told to focus their feelings, using randomly generated images of the rings that they were told represented nothing specific.

“We ask them to try to hold the feeling, to feel it as strongly as possible,” Moll said.

It worked. People who were given feedback on their brain patterns were able to strengthen them, Moll’s team reports in the Public Library of Science journal PLoS ONE.

“This demonstrates that humans can voluntarily enhance brain signatures of tenderness/affection, unlocking new possibilities for promoting prosocial emotions and countering antisocial behavior,” they wrote.

The approach needs a lot of fine-tuning, Moll stresses. But he envisions helping people who are having trouble controlling angry or violent emotions. You could see a use for someone with antisocial personality disorder, he said. “You could use it to reduce unwanted feelings.”

It might also help treat people with developmental conditions such as autism, some forms of which are marked by an inability to read and understand other peoples’ emotions.

And Moll’s team is also working to study psychopaths, although he hasn’t tried the fMRI/biofeedback technique on one yet.

“Maybe it wouldn’t work with a true psychopath, who never felt a droplet of tender feelings,” he said.

But not all people have extreme symptoms, and it might help some people understand that reading and mirroring others’ emotions could work in their own self-interest.