If dullness were a crime, the proceedings in courtroom 14B at the Southern District Court on Pearl Street would be a graver offense than the actual matter at hand: the insider-trading trial of Rajat Gupta, a former head of the consulting giant McKinsey and former board member of Goldman Sachs and Procter & Gamble.

Inside the room, a small cadre of onlookers staved off boredom last week as witnesses walked the jury through esoteric financial jargon and piles of telephone and building entry logs. One of Gupta’s daughters, seated in the front row of the viewing gallery, twirled her hair idly, her phone — like everyone else’s — having been confiscated by security downstairs.

At one point during the trial, now in its third week, the trickle of documents got so slow that Judge Jed Rakoff — the Southern District’s lovable crank — told both sets of lawyers to perk it up.

“I am in awe of our jury because they have managed to remain attentive,” he snapped.

But behind the snooze-worthy facade, the Gupta trial is anything but dull.

Gupta is by far the biggest fish to be caught in the Galleon Group insider-trading sting; the ringleader, Raj Rajaratnam, is currently serving an eleven-year sentence. Gupta, a friend and associate of Rajaratnam’s, stands accused of leaking corporate secrets to the porcine hedge fund manager on five different occasions.

Rajaratnam’s conviction was hailed as a coup for Preet Bharara, the crusading U.S. attorney from Manhattan’s Southern District who headed the insider-trading crackdown. But convicting Gupta would be even bigger — the government’s most prominent Wall Street get since Ivan Boesky.

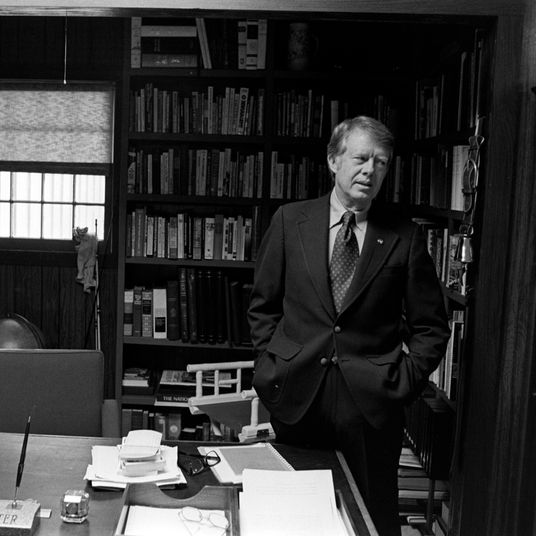

Much of the trial’s drama stems from the Icarus-like fall of Gupta himself. A regal-looking Indian immigrant, Gupta rose from nothing to build an enviable life — first non-American head of McKinsey, trusted advisor to CEOs all over Wall Street, inhabitant of a Westport mansion that was once owned by the retail magnate J.C. Penney. Gupta’s accomplishments are so comprehensive that they have become a strategy for his defenders — why, they ask, would such a lucky guy risk all he had by leaking secrets to a friend?

This week, Goldman Sachs chief Lloyd Blankfein will be among the witnesses to take the stand to help the government answer that question. Blankfein is expected to tell jurors that Gupta was a bad apple who played fast and loose with information about Goldman’s earnings, in violation of the bank’s policies.

Publicly throwing a former director under the bus is an odd step for a CEO of a company known for its discretion, but for Blankfein, the alternative to dropping a dime is much worse. Gupta’s defense team has sought to paint Goldman Sachs as a cesspool of illegal tipsters, any number of whom could have leaked information to Rajaratnam.

Calling Blankfein to the stand will also shed light on the difference between Wall Street’s twin currencies.

On Wall Street, people like Gupta and Blankfein are considered members of a class that has power, but not real money. In court last week, Gupta’s private banker estimated his net worth at $84 million — a fortune by any objective measure, but a fraction of what Rajaratnam and other hedge fund moguls are worth.

In a wiretapped phone conversation played for the Rajaratnam jury last year, Rajaratnam and Anil Kumar, a former McKinsey director, gossiped about Gupta’s financial insecurity.

“I think he wants to be in that circle,” Rajaratnam said of Gupta’s desire to take an advisory role at KKR, a private equity firm whose pay is among the top on Wall Street. “That’s a billionaire circle, right? Goldman is like the hundreds of millions circle, right?”

To most of the world, the gap between those circles is unimaginable. But prosecutors have said that it led Gupta to risk it all — his status, his reputation, his freedom — to impress a group of outlaws.

At heart, then, the Gupta trial is classic Wall Street — a tale of common envy and greed among the already insanely privileged.

And that kind of story should never put us to sleep.