In the summer of 2011, the conservative world was filled with giddy triumphalism. Through sheer determination, spurning all compromises, the GOP had turned the once-symbolic debt ceiling vote into a profitable hostage-taking opportunity. Even as Democrats controlled the White House and half of Congress, they had forced Democrats to accept more than a trillion dollars of domestic spending cuts, with no new revenue at all.

Republicans gloried in the weakness of Obama’s negotiating style. “He was, as he said, bluffing,” smirked Paul Ryan. “It may be blackmail. But it is progress,” gloated Charles Krauthammer. Ross Douthat, in a tone not of triumph but actual concern, persuasively explained that Obama’s unwillingness to hold a strong line on taxes made any compromise impossible:

Much of the Republican “intransigence” and “hostage-taking” and “terrorism” that they deplore is a direct consequence of the fact that Republicans assume that Democrats will always, always, cave on taxes. And so long as that assumption keeps getting vindicated by events, there’s no incentive for the G.O.P. to accede to sweeping compromises on deficit reduction. Why would you compromise with a party that won’t actually fight for the revenues required to pay for the programs it claims to want to protect?

Now Obama is taking this advice and actually forcing Republicans to negotiate rather than just roll him. The range of reactions on display is fascinating, and not necessarily what one might expect. You have doleful resignation from, of all people, Ann Coulter. You have spiteful resentment, like this from Kimberly Strassel (“[Obama] faces four years and 20 days of a presidency marked by his ownership of a faltering economy, a spiraling debt problem, automatic sequester cuts, no prospect of further spending or tax revenue, and a debt-ceiling time bomb. If that’s this president’s idea of “victory,” maybe it’s what he deserves.”) You have sheer self-pity, like the kind exhibited by one anonymous Republicans speaking to Byron York:

“We’re in a tough situation,” says the senior House Republican. “If we could not get a good agreement in 2011, when we had just picked up 63 seats in the House and six in the Senate, how in the heck are we going to get a good deal now?”

Well, they actually could get a good agreement in 2011. They just turned it down. But never mind.

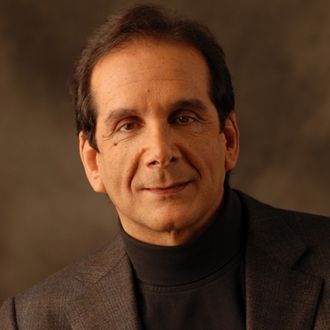

For sheer impotent rage, you cannot top Charles Krauthammer’s column today. That Krauthammer is a trained psychiatrist, not to mention perhaps the most influential conservative pundit in America, makes his display of incoherent sputtering pique all the more mesmerizing. It is a document that truly rewards close study.

Krauthammer begins his column by sneering at Obama’s “landslide 2.8 point victory margin.” In fact, with votes still being tabulated, Obama is currently leading by 3.6% and rising — a reasonably healthy lead in comparison with, say, the 2.4 percent victory for George W. Bush in 2004, which Krauthammer at the time called “a large majority, or a significant majority.”

Krauthammer expressed his outrage that Obama, using this oh-so-slender victory margin, opened the negotiations by asking for the extortionate sum of $1.6 trillion in higher revenue. (Less than the Bowles-Simpson plan, by the way.) This, fulminates Krauthammer, is “not a negotiating offer but a demand for unconditional surrender.” Krauthammer’s rage is unmitigated by the fact that Obama explicitly and repeatedly offered to negotiate from his opening bid, and that he’s not “demanding” anything except the extension of the tax cuts on income under $250,000, which Republicans also favor.

Krauthammer proceeds to argue that the entire point of the negotiation — or, rather, “demand” — is to humiliate the poor Republicans rather than actually reduce the deficit:

As for the alleged curative effect on debt of Obama’s tax-rate demand — the full rate hike on the “rich” would have reduced the 2012 deficit from $1.10 trillion to $1.02 trillion.

That’s a joke, a rounding error.

It is certainly true that Obama’s proposal would have minimal effect on revenue in year one. In part that’s by design — if it sucked a huge amount of revenue up immediately, Krauthammer would (justifiably) complain that Obama was proposing to induce a new recession. But Obama’s revenue plan would leave a serious dent in the long-term deficit. If Krauthammer doubts this point, I would refer him to six paragraphs earlier in his own column, in which he bemoans the vast $1.6 trillion in higher revenue Obama’s proposal would raise.

Krauthammer fleshes out his charge by noting that “Obama has never shown interest in genuine debt reduction.” The reference to “genuine” debt reduction is Krauthammer way of turning the question from the mathematical definition of debt reduction — the gap between revenue and outlays — to his more congenial one, in which revenue is irrelevant:

Obama has never once publicly suggested a structural cut in entitlements. On the contrary, he created an entirely new entitlement — Obamacare — that, according to the Congressional Budget Office, will increase spending by $1.7 trillion over 11 years.

Krauthammer notes that Obamacare “increases spending,” which is true. But he doesn’t note that it reduces the budget deficit, which is a relevant point in the context of Krauthammer’s larger contention that Obama does not care and has never cared about deficits. It’s also interesting that Krauthammer accuses Obama of never having “suggested a structural cut in entitlements.” Remember that $716 billion cut in revenue? It was decried as recently as this August for its vastness and abject cruelty by such figures as Charles Krauthammer. (“It’s a huge real cut, it’s going to effect the elderly.”)

Krauthammer concludes his rant by urging Republicans to insist on extending every penny of the Bush tax cuts. (Apparently this will prove that they, and not Obama, are serious about deficits.) Krauthammer barely deals with the obstacles to such a course that have dissuaded the GOP. Conservatives tend to cherish tribal unity and strength, and Krauthammer is appealing to these traits at an almost primal level. His argument centers on the symbolism of humiliation and strength. He claims that Obama wants Republicans “neutered” and employs a metaphor about Republicans keeping their trousers, the symbolic import of which I’ll leave unanalyzed here, and concludes with a rousing call:

Most important of all, however, Republicans will still be in possession of their unity, their self-respect — and their trousers.

Unity! Self-respect! Trousers! A fitting approach indeed for negotiations over the federal budget.