The Hillary 2016 presidential speculation carnival is in full swing. And her ancient past, including a 1998 slam of Monica Lewinsky as a “narcissistic loony toon,” still manages to generate new headlines. Yet four of the most meaningful years of Clinton’s public career, as Secretary of State under President Barack Obama — a time when she was risking the lives of diplomats to try to spread democracy — have somehow gone underexamined. That’s why the newest book in the vast Clinton library is significant. HRC: State Secrets and the Rebirth of Hillary Clinton manages the rare feat of being both important and entertaining. It opens with a juicy chapter detailing the punishment and reward of Bill and Hillary’s political enemies and friends. But the meat of HRC is its narration of her role in tackling crises in Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, and Libya — an amazingly tumultuous period that provides the best preview of what a Hillary Clinton presidency might look like, at least for foreign policy. Daily Intelligencer spoke with the co-authors of HRC, Amie Parnes, a reporter for The Hill, and Jonathan Allen, of Bloomberg News.

Did Hillary’s visible efforts in Pakistan — meeting with its leaders, improving relations — make possible covert actions, up to and including the killing of Osama bin Laden?

Allen: What we saw, in our reporting, was a hand-in-glove relationship between the diplomacy end and the intelligence/military end. Those things are hard to see, because it’s not like the United States is advertising its strategy to Pakistan.

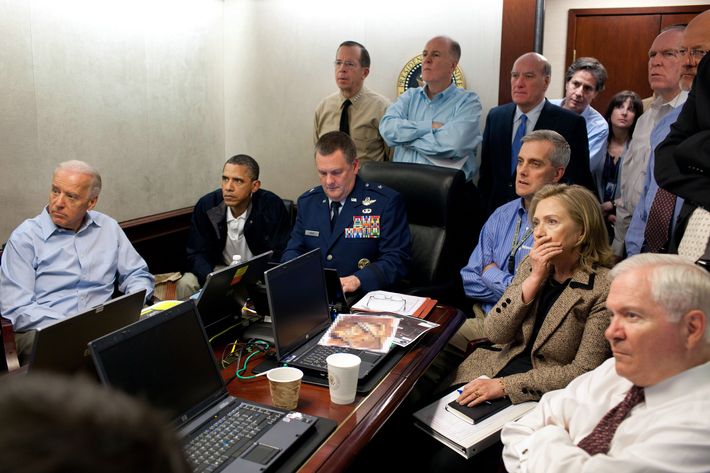

Parnes: When the bin Laden raid was being planned [then-CIA director] Leon Panetta wanted buy-in from Hillary, because she’s such a hawk. He sees her in the Situation Room and tells her he wants to talk, and then they meet for lunch in a secret meeting that not even her closest aides knew about.

You describe a remarkable scene, in a 2011 confrontation over drone strikes in Pakistan, where Panetta and Hillary yell at one another.

Allen: They both felt very comfortable having it out. Hillary and Panetta, unlike some people who get to a high level in the national-security apparatus and are afraid to fight in front of the president, they had no qualms about it.

One theme in the book is Hillary’s “bias for action,” a preference for taking risks and trying to manage them rather than avoiding risks completely. Yet she showed an abundance of caution when Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak was clearly on his way out. Did Clinton misread the revolution?

Allen: They were appropriately worried about what would come next. But the Clintons’ friendship with Mubarak, who had been helpful to the United States over the previous decades, was another factor. They felt like they owed him some allegiance. And I don’t think anyone in the national-security apparatus was prepared for just how limited America’s influence would be with regard to the Arab Spring. [As Mubarak clung to power,] they were hand-editing the statements on Egypt right before sending them out. It was like the movie version of what would happen to a presidential statement rather than the reality of what usually happens.

Parnes: Obama was significantly more forward-leaning [on Egypt] than she was. It stands out as one of the few instances were there was daylight between them.

You show how Hillary advocated “expeditionary diplomacy,” pushing diplomats into volatile areas. Was that a strategic choice?

Parnes: It’s more a reflection of her personality, and you saw that not just in Libya, but in the Afghanistan surge and the bin Laden raid.

Allen: It’s also taken from the experience of the Bush years, where you had soldiers doing diplomacy and development, building schools and talking to people. The footprint of American foreign policy was a combat boot rather than a wingtip. There was a real desire, by both the president and Hillary, to start talking to the world with something other than our guns. It’s risk to have diplomats in places where there isn’t a big military presence.

Did the disaster of Benghazi, and the murder of Ambassador Chris Stevens and three other Americans, reduce her tolerance for risk at all?

Allen: Hillary believes the attack in Benghazi isn’t a reason to pull back American diplomats.

Parnes: It’s a philosophy she feels strongly about. If she were still there, at State, I don’t think she would change it. But she would take a different approach to protect people.

Allen: There’s nothing she’s said that suggests she’d want to back off that basic philosophy of having diplomats out there as the first line of foreign policy. That’s in many ways a more important debate to have than the proper number of security officers to have in Tripoli—the question of whether you have largely unsecured people doing your diplomacy for you, or do you need to have a heavy military presence alongside them? It’s something Hillary should answer if she runs for president.

You revisit the furor over Susan Rice’s Benghazi “talking points.” Did Hillary have any role in creating them?

Allen: What we’ve seen publicly is not the complete record of the conversations that went on regarding the talking points. We talked to officials who said it’s a small slice of what was actually going on in conversations among national security officials. But there’s no evidence, at this point, that Hillary weighed in directly.

There’s also a fascinating glimpse of why it was Rice, and not Hillary, on the TV hot seat.

Parnes: Her aides knew what might happen, and they tried to shield her from the Sunday shows. And one of their defenses on this is Hillary doesn’t like the Sunday shows and doesn’t do them very often.

Hillary appeared to go to great lengths to stay out of politics while at State, at least publicly. Yet the book describes how that’s not accurate, or even realistic, given Bill and Hillary’s ties and talents. At one point she’s in London on government business, then calls a Democratic congressional candidate in Buffalo.

Allen: It was important for her political standing to pretend to be, or project herself to be, above politics. And yet time and again we found her nosing into domestic politics. She got involved in the health-care debate, she called candidates. Congressman Howard Berman tried to get Bill Clinton to back off from supporting Berman’s opponent in a California Democratic primary … Eventually Berman goes to Hillary when she’s lobbying him on a trade bill: “How can I vote for this when your husband is campaigning against me?” She says, “I’m out of politics,” and laughs. It’s not like she couldn’t make a phone call to Bill and say, “Hey …”

The book traces the evolution in the relationship between Obama and Hillary. In 2008, they were bitter rivals. By 2013, when she’s leaving State, they seemed close, both professionally and personally. How genuine was the affection?

Allen: In 2008, a lot of her closest aides were mortified at the prospect of working with her. In the first year, during the Afghan surge, there was a lot of suspicion of her motives, because she’d lashed herself to Gates and the military. By the end, the people who were still upset with her were generally not the ones working with her on national-security issues. Some of Obama’s political people still dislike her.

Parnes: The president wanted her to stay. Every aide we spoke to said they loved the work she did, and I don’t think that was bullshit at all.

The Clintons don’t cooperate with many books — and have actively obstructed some projects about them. How did you get so much access, including fresh quotes from Hillary?

Allen: The whole thing was a negotiation, with ups and downs. We were serious about writing a fair book that wasn’t a hit job, and that was helpful [to the reporting process]. The desire to have a story out there that wasn’t just her own upcoming book played into it — if they talked to us, at least some of their story would show up in our book.

Parnes: They felt like political reporters’ Rolodexes were stuck in 2008, and we were willing to look at some turf a lot of people hadn’t. People hadn’t focused on her time at State. They felt like it was worth us telling that story, what she really did at State. But I’ve heard from multiple people in Clintonworld who are not happy.

Allen: There was a lot of consternation over the first excerpt [about the political “hit list”]. Nobody likes to have it out there that they are keeping lists and exacting payback.

Clinton haters, and even some friends, believe everything they do is calculated to serve their political ambitions. Did you see that in the choices Hillary made at State?

Parnes: It sounds geeky and naïve, but she really believes in public service. She has this philosophy, that she talks about at the end of the book, that comes from John Wesley, about “a sense of obligation.” You kind of want and have to believe her.

Allen: Most good politicians know that the best way to audition for the next job is to do well in the job they have now. I’m sure there are plenty of things she did or didn’t do based on the politics, but when you talk about things like attacking Osama bin Laden, there’s a lot of risk in joining the president on that. If that had gone down poorly, with Obama and Clinton for it and Biden and Gates against it, that wouldn’t have augured well for a Hillary presidential campaign, much less Obama’s reelection. But for years she’d asked at hearings and meetings, “Where’s bin Laden, what are we doing to get bin Laden?”

What do you think her years at State say about what kind of president Hillary would be?

Parnes: She’d be someone who is incredibly decisive, and who is really loyal to the people around her.

Allen: And she’s someone who takes on challenges that aren’t necessarily the sexy, political winners. Instead, in a glutton-for-punishment way, she looks to move the needle a little bit on issues she thinks are important. One of the challenges for her going into 2016 will be articulating a vision for the future. One of the things she was better at in the State Department was the day-to-day operations — the stable, competent management of a government bureaucracy.

Now there’s a campaign slogan.

Allen: [laughs] Right. But she doesn’t have a big Middle East peace deal to point to.

So what are the chances she runs in 2016?

Parnes: Ninety-nine point —

Allen: — nine-nine percent. We’re in agreement.

Parnes: There’s no doubt in my mind. Something really severe would have to happen. She met with Gillibrand and Schumer, within weeks after leaving Foggy Bottom, to talk politics, conversations about what a 2016 campaign would look like.

Allen: She’d have to stop running, not start running.