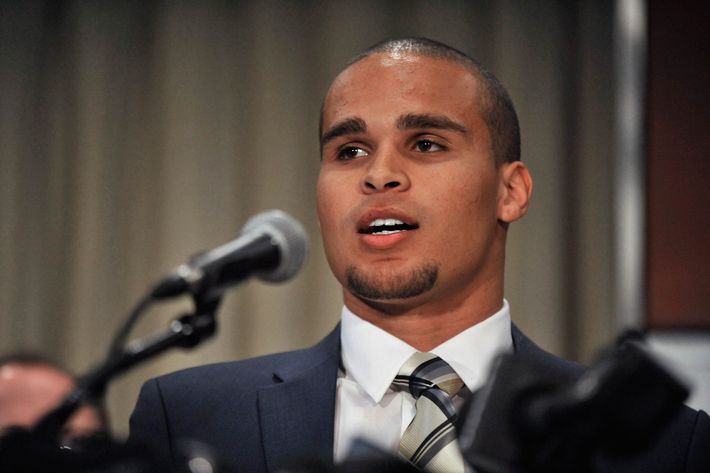

Northwestern University quarterback Kain Colter announced last week that he and his teammates have filed a petition to form a union. The news has been received joyfully by the most implacable haters of college athletics as the latest evidence that the whole edifice of amateurism is crumbling down. To the contrary: The unionization movement is the very thing that might restore and save the institution.

Everybody agrees that college sports have some serious problems. The disagreement lies in what those problems tell us, and what we should do about them. The most common line of attack, suggested by numerous writers at the New York Times, especially Joe Nocera, but also several other critics, is that college sports are fundamentally a lie. They’re professional sports disguising themselves as amateur endeavors. The solution is to strip off the mask and openly professionalize the sports as a way station to abolishing them altogether (though they are cagey on this point). But the premise is that college athletes are workers, the fruits of their labors are being confiscated by a cartel, and the solution is to allow the natural market to work.

This analysis works well as a polemic, but tends to fall apart when it gets anywhere close to a plan of action. I’ve laid out my critique of this highly fashionable line before. The trouble, in a nutshell, is that imagining college athletes as an unpaid labor force misconstrues the situation almost completely. Matthew Yglesias, in one of his arguments assuming college sports as a simple market constrained by hypocritical assertions of amateurism, writes, “the top prospects have economic value.”

That’s true. But the vast majority of college athletes have negative market value. A reform based on letting them capture their true market value is going to fail to protect the interests of the vast majority of college athletes. This includes not only every athlete in a sport other than football or men’s basketball (which of course includes all-female athletes), but also many of the players who participate in the most competitive football and basketball programs.

One way to see this is to look at the biggest problem currently afflicting college football players: oversigning. Currently, every football program has a limit of 85 scholarships it can hand out at any given time. Traditionally, football players who are granted scholarships get to keep those scholarships for four years, unless they flunk out of school or commit serious violations of school rules. Recently, some programs, mostly in the Southeastern Conference, have figured out that if they can nudge weaker players off the roster, they can make room for more recruits every year. The site oversigning.com has tracked this abuse. Roll Bama Roll, an Alabama blog, has a mortified post facing up to the fact that Nick Saban simply has to cut seven players from the football roster to make room for his new recruits.

If you consider college sports to be merely professional sports in disguise, you probably don’t have a problem with oversigning. (Pundits who want to professionalize college sports generally don’t follow the sport closely enough even to be aware of it.) Professional franchises cut weak players from the roster every year. That’s just how a competitive market works.

The rise of oversigning reflects the degree to which the sport has become more like a competitive market in recent years. John U. Bacon has a new book, Fourth and Long, in which he reports closely on the experience of players at four college football programs and shows how the increasing power of market forces threatens those players. One of the programs he describes is at Northwestern, and it’s also the program among the four that most closely hews to the ideal of the student-athlete.

Bacon has suggested reform proposals for college sports, which would be designed to protect the ability of the vast majority of college athletes to balance school and sports, and which run along similar lines to what I’ve advocated. Yes, the most economically successful athletic schools could divert some money to stipends to cover the actual cost of attendance, but that money would be distributed equally to all athletes, not just the handful of football and men’s basketball players who command market power. The main reforms would be to create a five-year guaranteed education, including universal freshman ineligibility. Rather than a total scholarship cap, every program would be granted a fixed number of new scholarships to allocate every year, which would eliminate the incentive to run weaker players out of school.

Market forces are not the solution to the problems of college athletes; they’re the cause of them. A handful of football and men’s basketball players are stuck in colleges for the sole purpose of preparing for professional sports. But most college athletes understand the value of a college degree, because most Americans understand the value of a college degree. What they want is to be able to balance commitments to sports with their ability to take advantage of their educational opportunity and to have the chance to live a semi-normal college life.

Those are the sorts of goals unions are perfectly positioned to help them fulfill. The union activists are not looking to make a handful of football and basketball players rich. Their goal is to protect the health and welfare of overstressed college athletes. As Nocera reports:

[N]either Colter nor Huma is advocating that the players get paid a salary. “What we want is a seat at the table,” said Huma. What college athletes need, more than money, is an organization that will push back against the all-powerful N.C.A.A. and their own athletic departments, which are so quick to throw their players under the bus at the first hint of a problem.

The movement is starting with Northwestern football players, but there’s no reason for it to be limited either to Northwestern or to football. All athletes face stresses on their time and health. The players with the least economic value often need the most protection. A union is the kind of institution that’s perfectly designed to implement Bacon-style reforms and insulate its members from the distortions of the market.

Binding together the interests of the minority of athletes who have market value with the majority who don’t would fatally undercut the premise of the critics who want to treat college athletes like professionals. Unions aren’t going to give college athletes professional-type salaries. They could ensure that all athletes, football players, and women’s volleyball players alike, get scholarships that reflect the true cost of attendance. (The biggest schools are already pushing the NCAA to approve this reform – the holdouts are the smaller athletic programs already facing financial pressure.) They can negotiate long-term access to health benefits covering any sports-related injury, limit their training obligations, and protect their ability to enough time on campus to complete a real degree if they want one.

Unionization won’t satisfy the demands of pundits who are certain college sports are nothing but a lie. Precisely because they wouldn’t do that, what they can do is improve the welfare of college athletes and restore the ideals of an institution facing a mortal threat.