The biggest victim of the Ukraine crisis – other than the Ukrainians themselves, of course – may be Rand Paul. Since bursting onto the national scene four years ago, he has labored steadily and shrewdly first to shed his kook label, to make himself acceptable to the Party’s establishment, and then to steadily tug its policy agenda in his direction. His high-profile attacks on the Obama administration’s foreign policy agenda have excited conservatives and made traditional hawks do a slow boil.

But the return of a classic Cold War scenario has awkwardly exposed the dissonance between conservatives’ still-strong nationalist impulses and Paul’s isolationism. Paul has an op-ed in Breitbart’s “Big Peace” weakly making the case that Ronald Reagan was more dovish than you think, and pleading against his critics, “splintering the party is not the route to victory.” Concurrently, he has an op-ed in Time laying out his plan of action in Ukraine. The Time op-ed is where Paul truly lets loose his long-suppressed inner kook.

Everything about Paul’s argument is weird. Part of the weirdness is conveyed by the prose, which is bereft of specific facts, repetitive, and reads as if it were run through a foreign-language translation program (“This does not and should not require military action. No one in the U.S. is calling for this … I have said, and some have taken exception, that too many U.S. leaders still think in Cold War terms and are quick to ‘tweak’ the international community. This is true.”)

The most uncomfortable thing about it is watching Paul attempt to steer the Ukraine debate toward appropriately Paul-esque solutions. He begins by endorsing the basic Republican talking points, which revolve around (1) general calls for more tough leadership by Obama; and (2) exporting more natural gas to western Europe. (Steve Mufson explains why the latter would have at best a delayed, very marginal effect.) But Paul adds other ideas, too. Some of them reflect an apparent inability to follow the news, like his ringing call for a boycott of the next G-8 summit in Russia:

The U.S. should suspend its participation in this summer’s G-8 summit and take the lead in boycotting the event in Sochi.

Yeah, this already happened.

Paul goes on to argue, “America is a world leader, but we should not be its policemen or ATM.” So he’s saying the United States should lead the world, but this leadership should not entail any new financial or military commitment? Actually, he’s going farther than that. He’s arguing that American leadership should involve less financial and military commitment. Paul’s plan entails stiffing the Ukrainians:

We should also suspend American loans and aid to Ukraine because currently these could have the counterproductive effect of rewarding Russia.

Yes, you read that right – in the face of a massive threat from Russia, the United States should impose financial penalties on Ukraine.

Likewise, Paul demands that Obama “lead” our allies in Western Europe, but proposes we stiff them, too:

I would reinstitute the missile-defense shields President Obama abandoned in 2009 in Poland and the Czech Republic, only this time, I would make sure the Europeans pay for it.

You may be wondering just where this plan to lead our allies by treating them like ungrateful punks is going to work. Let Paul explain:

Russia, the Middle East or any other troubled part of the world should never make us forget that the U.S. is broke.

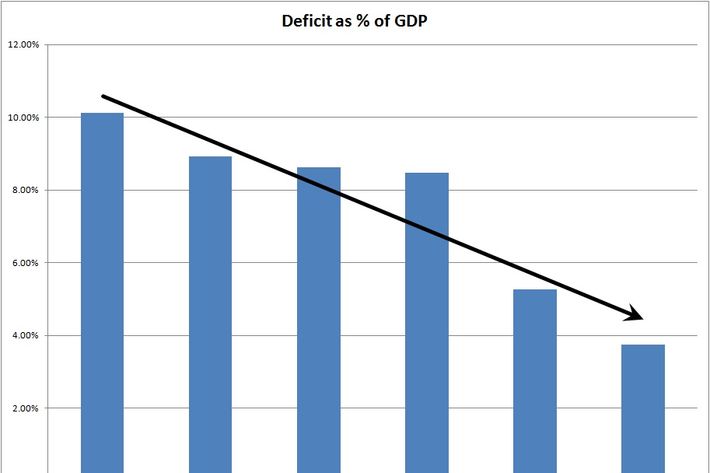

FYI, we’re not broke, we were never broke, and we’re getting farther away from being broke every year.

If you haven’t figured out where Paul is going with this, the next sentence lays it out:

We weaken our security and defenses when we print money out of thin air or borrow from other countries to allegedly support our own.

Yes, the solution to Ukraine’s trouble is for the United States to adopt the gold standard. Of course.

The painful ideological gyrations on display here show that the much-hyped libertarian resurgence within the Republican Party was never as solid as it appeared. Paul was able to rally Republicans to his side because he could position his anti-drone, anti-surveillance policies as the strongest opposition to Barack Obama. Now Vladimir Putin has created a situation where the most obvious line of attack sits to Obama’s right. News analyses in the New York Times (“Ukraine offers a moment for hawks like Mr. Rubio to reassert themselves”) and the Wall Street Journal (“The Ukraine crisis has given GOP foreign policy hawks a fresh opportunity to reassert themselves”) both reaffirm the hawks-strike-back narrative.

Left unsaid is that the rise of Republican anti-interventionism was a partisan phenomenon, not an intellectual one. During the 1990s, Republicans in Congress assailed the Clinton administration’s military interventions in the Balkans, and George W. Bush ran promising a more “humble” foreign policy. The same dynamic works on Democrats, whose civil libertarian impulses spike during Republican presidencies and recede when a friendly Democrat occupies the White House.

Paul’s foreign policy ideas worked for him when he could exploit partisan fear of Barack Obama. Now his intra-party rivals are exploiting the more obvious line of attack on Obama as a wimp in mom jeans. So Paul is stuck trying to peddle isolationism, the gold standard and telling Europe to pound sand as solutions.