The most recent forecast by Fivethirtyeight gives Republicans a sixty percent chance of winning a majority of the Senate in November’s elections. Given that any bill already has to pass the Republican-controlled House, the effect of a Republican Senate upon President Obama’s legislative agenda can be calculated at zero, with a margin of error of zero. You can’t kill something that is already dead.

On the other hand, what is currently alive, albeit barely, is a fragile peace that has enabled the functioning of the traditional separation-of-powers relationship between the branches of government. The survival of that peace depends entirely on a Democratic Senate. Almost nobody seems to be thinking about the potential chaos that could lie ahead.

The Constitutional crises of 2013 were numerous enough to blur together. The most easily resolved took place when Senate Republicans began wholesale barricading of various judicial and executive branch appointments by the Obama administration. Previously, the Senate tended to block candidates in rare and particular circumstances — say, if they were unusually radical or unqualified, or sometimes in response to a particularly bitter fight over a previous candidate. Last year, Senate Republicans declared they simply would not allow any Obama nominees for various positions in the executive branch whose functioning (like enforcing labor law or regulating Wall Street) they did not care for. They likewise announced that they would not permit any new judges to the powerful D.C. Circuit because the court was balanced between the two parties and Republicans wanted to keep it that way. This escalation amounted to a major revision of the balance of powers — if it held, a hostile Senate could paralyze any agency it desired, or prevent a president from appointing anybody to the federal bench.

Senate Democrats resolved the standoff by changing the Senate’s rules to ban filibusters for executive branch nominees and federal judges. This was the “nuclear option” — a dreaded unilateral alteration of the chamber’s rules. Republicans and respectable centrist observers alike predicted the nuclear option would unleash terrible and indescribable consequences. The nuclear option turned out to defuse the conflict. Obama has gone ahead filling administrative and judicial appointments, none of them especially offensive to the Republican minority, and the crisis dissipated, as if into thin air.

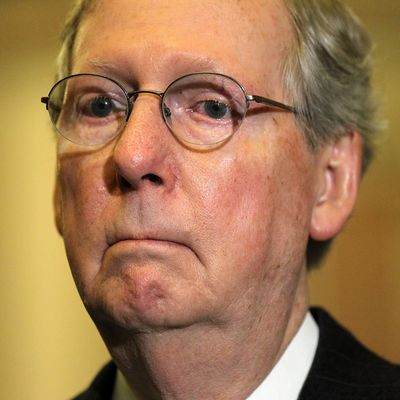

But the solution turned out to hinge on particular, and likely temporary, circumstances. The first, of course, is a Democratic Senate majority. The nuclear option stops a Senate minority from wantonly blockading vacant posts, but it does not stop a Senate majority from doing so. A prospective majority Leader Mitch McConnell may use his power to reimpose or even expand the blockade of 2013. Just what level of havoc this would wreak is hard to figure; Obama has filled his major executive branch vacancies and steadily appointed judges to vacant posts. Perhaps the administration could muddle through a final two years of total paralysis. Perhaps not.

The potential for true crisis lies in the smaller possibility of a Supreme Court vacancy. The Democrats’ nuclear option allowed them to fill a regular judicial seat with a straight majority vote, but did not allow them to fill Supreme Court seats this way.

Imagine 75-year-old Stephen Breyer, or 81-year-old Ruth Bader Ginsburg, decides to retire. Perhaps they suffer a health setback, or simply grow tired of the grinding conflict, or perhaps warm to the logic of stepping down when an ideologically friendly jurist is likely to replace them.

Would the Republican majority let Obama appoint a mainstream center-left nominee to the seat? The last vacancy occurred in 2010, before Republicans swept into control of the House. Even though Obama’s nominee, Elena Kagan, possessed sterling bipartisan support, a mere five Republican senators voted for her confirmation. Three of them — Richard Lugar, Olympia Snowe, and Judd Gregg — have departed, and the GOP caucus emerged from the 2010 Tea Party wave filled with terror at any vote that could even hint at ideological treachery.

Now imagine a different possibility. Suppose one of the five Republican-appointed seats opened up. None of them would voluntarily surrender a seat at the end of a Democratic president’s tenure, of course. But when the hypothetical gavel transfer to Mitch McConnell takes place next January, Antonin Scalia and Anthony Kennedy will both be 78 years old. The actuarial odds of a 78-year-old man dying within a given year are approximately 5 percent — we will have two of them, with two years of Obama’s term each. (The odds of death rise to 5.6 percent at age 79, for those morbidly inclined.) We are not talking about a freak occurrence.

What would happen then? Would a Republican Senate let Barack Obama — fundamental transformer of America, shredder of the Constitution — appoint a new swing justice? Given a backdrop in which conservatives, having grown deeply pessimistic about their political future, have invested deeply in a legal movement that uses aggressive readings to roll back the state? With every conservative interest group mobilizing for battle, with a vast array of social and economic policy hanging in the balance?

It may seem implausible that Republicans would simply refuse to allow Obama to appoint any justice to such a vacancy. That is only because things that haven’t happened before are hard to imagine. But such a confrontation is not only a logical outcome but the most logical outcome. Voting to flip the Supreme Court would be, if not a political death warrant for a Republican Senator, then certainly taking one’s political life into one’s own hands. Politicians do not like political death warrants — certainly not for the benefit of the opposing party’s agenda.

The modern pattern in American politics is that tactics that are legally available, but never used for reasons of custom, eventually become used. The modern pattern is also that the Republican Party, which is the most ideologically cohesive and disciplined party, leads the way. McConnell did not create this pattern, but he is an important innovator.

McConnell was among the first political leaders to grasp that Republicans had everything to gain and nothing to lose from withholding support for every major element of Obama’s agenda — that the old Beltway folklore, which warned the opposition party that voters would punish them if they appeared obstructionist, had no basis in reality. Most people pay no attention to the details of policy, and form rough judgments on the basis of how much noise and controversy rises out of Washington. “It was absolutely critical that everybody be together because if the proponents of the bill were able to say it was bipartisan, it tended to convey to the public that this is O.K., they must have figured it out,” he confessed. Political scientists understood this reality perfectly well, but it was utterly strange to the old-line purveyors of Washington conventional wisdom. McConnell moneyballed the Senate.

It stands to reason that if and when new powers are laid at his disposal, McConnell will once again deploy them creatively. A potential Supreme Court crisis, in which the Senate simply refuses to let the president fill a vacancy on any remotely normal terms, is one possibility. Others may be brewing at this moment deep within McConnell’s extensive imagination.