The return to preeminence of the Clintons was supposed to signify a renewed economic populism that would define the Democratic Party. It was, after all, Hillary Clinton who quaffed beers with white working-class Democrats in her 2008 campaign against the abstract, yuppified idealism of Barack Obama. And it was Bill Clinton who, in a 2012 Democratic National Convention speech, folksily explained the party’s economic philosophy more concretely than Obama himself had ever managed.

And yet, in the wake of a stream of disclosures and clumsy statements, the class narrative has turned sharply against the Clintons. The Arkansas populists find themselves rendered as plutocrats. Democrats are fretting (“It’s going to be a massive issue for her,” an Obama adviser tells Phillip Rucker”) and Republicans are gleefully hurling the sort of Romney-car-elevator abuse that they so miserably endured. How has Hillary Clinton been suddenly transformed into Marie Antoinette? The new narrative, like most political narrative, is an amorphous mix of fact, pseudo-fact, spin, and self-fulfilling prophecy, which is easier to understand if we pull apart the various threads and analyze each individually:

1. Clinton’s most recent comments, the ones that finally caused her class problem to leap over the breach from a series of isolated episodes to a full-blown media narrative, are overblown. Here is what she said:

But they don’t see me as part of the problem because we pay ordinary income tax, unlike a lot of people who are truly well off, not to name names; and we’ve done it through dint of hard work.”

Reporters have widely portrayed this as Clinton distinguishing her income from “people who are truly well off.” That isn’t quite right. Her comments, while slightly garbled, seemed to be defining “the problem” not as high income but as special tax breaks enjoyed by the rich. She was separating herself from wealthy tax-dodgers, not the wealthy writ large.

Likewise, the fact that the Clintons engaged in estate planning, which also led to a mini-wave of scandalized reporting and commentary, is not a scandal, either. Clinton favors the estate tax, which is not the same thing as believing people should individually pay more taxes than they owe the government.

2. On the other hand, her previous controversial comments, in which she claims she and Bill were “dead broke” after leaving the White House, were truly delusional. Whatever the literal dollar figure in their bank account the day they left 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, the Clintons had a six-figure lifetime salary and generous pension awaiting them, along with unlimited earning potential.

3. But how the Clintons took advantage of that earning potential poses both a problem of perception and a problem of substance. The Clintons have attached themselves financially to a wide array of interest groups and interested individuals, some of them quite venal. The Clintons’ buckraking has been swept up into the “out-of-touch” narrative, but it actually represents a far more alarming concern about good government.

4. Lurking quietly and mostly unnoticed in the background is the possibility of an Elizabeth Warren primary challenge. Warren is vying for a position of national leadership among liberal activists, and any upsurge in progressive discontent with Clinton — or, for that matter, President Obama — will flow toward demands that Warren challenge Clinton. Will she do it? Probably not, but Warren is pointedly leaving the door open. She has deflected questions by repeating “I am not running for president” — an ambiguous phrasing that could describe future intent, or could simply describe present conditions (I am not, at this very moment, running for president).

Ruth Marcus pressed Warren on her formulation, and Warren supplied a revealing non-answer:

Why not simply declare that she will not run for president in 2016? “I am not running for president in 2016,” Warren responded. Yes, I pressed, but why not say, I am not running and I will not run?

“Because we can’t get so deeply involved in the politics of 2016 that we miss the importance of the issues in front of us today in July of 2014 and the 2014 election.”

To be sure, even if she runs, Warren would stand little chance of winning, but she certainly could provide the Clinton out-of-touch story with months and months of narrative reinforcement.

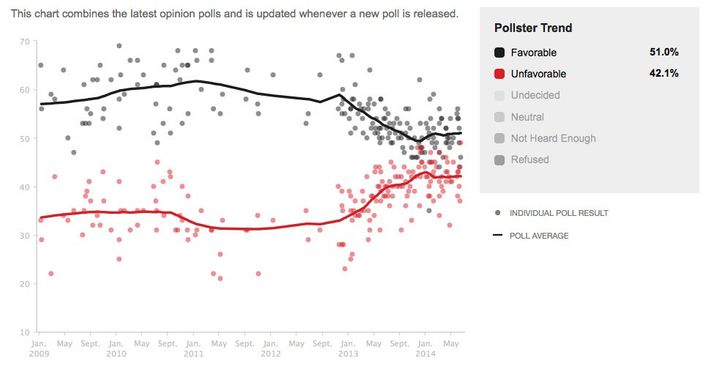

5. Clinton’s surprising struggles in her de facto campaign rollout have raised renewed questions about her political skill. There are two points to bear in mind when assessing her talents as a public communicator. The first is that her lofty approval ratings were entirely the function of her absence from partisan politics, and they are gravitationally plummeting as she reenters the political context:

The second point is that Clinton’s association with white working-class populism owes a great deal to the fact that she ran against a black person in 2008. This is not to say that Clinton manipulated racial animosity, but that she became the vessel for voters uncomfortable with a black presidential candidate.

Political scientist Michael Tesler, whose work I’ve cited before, has measured the degree to which race dominated the public consciousness during Clinton’s 2008 primary campaign. The Democratic primary campaign split racial liberals against racial conservatives, to the point where Clinton’s intrinsic qualities became nearly irrelevant. Tesler has highlighted the amazing fact that the most feminist Democrats supported Obama, while the Democrats with the most traditionalist views of gender supported Clinton. “Three different surveys,” he writes, “show that Hillary Clinton performed about 15 percentage points better against Barack Obama with strong gender traditionalists than she did with Americans possessing the most liberal beliefs about gender roles.”

What could explain this astonishing inversion? Views on gender correlate highly with views on race. Clinton attracted racial conservatives, who happened to be gender conservatives as well. But white racial conservatives flocked to Clinton primarily because she was white, not because she bowled or knocked back shots with special aplomb.

6. The Clinton name still gives her a certain economic cachet. The last time the American economy created rising middle-class living standards came with the Clintons in office. That is the sort of heuristic that swing voters, who tend to be low-information voters, can easily grasp.

7. Clinton’s economic profile is being defined in personal terms in part because she has neither a platform nor an opponent. As the likely nominee, she will have both, and thus the opportunity to contrast her policies against a Republican Party still wedded to the upward redistribution of income as its central policy goal. Republicans will probably try to redefine the economic debate as a personal question rather than a policy question — especially if they nominate a candidate who is not ostentatiously rich — but Clinton will have weapons at her disposal not currently available.