The joke started circulating during the third Bill de Blasio–Bill Bratton event of the week. Or maybe it was the fourth; in the sad, strange blur that followed the shootings of police officers Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos, the joint appearances by the mayor and the police commissioner ran together. “Ah, the mayor’s understudy,” mumbled one reporter as Bratton stepped to the microphone. Then, awaiting the fifth episode of this show, the wisecrack expanded to the full Playbill-insert treatment: “At this evening’s performance, the role of ‘the Mayor’ will be played by Bill Bratton.”

Like many good jokes, this one was unfair: In every instance, de Blasio got top billing; he usually spoke first, and sometimes he spoke longest. But like all good jokes, it contained an element of truth. Bratton was the one who seemed to have the greater confidence and the defter feeling for the mood of the room, and not just because the subject was the NYPD. The short-term political calculation was fairly obvious; with de Blasio the target of ferocious anger within the department, stepping back and letting the PC dominate the spotlight could defuse some of the tension.

But the December protest-and-police melodrama highlighted an operating style that had been emerging throughout de Blasio’s first year in office. It’s a shift from his two predecessors more radical than any policy change de Blasio has attempted. And it’s either ingenious or doomed to leave the mayor crippled.

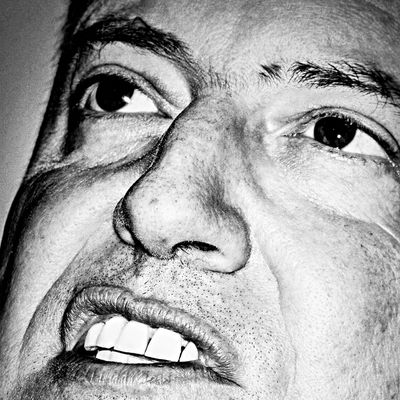

Bill de Blasio is willing to take punches. That seems like an odd way to describe one strategic posture of a man packing a bold agenda to reorient government from an enabler of the elites to a champion of the powerless, but that’s the phrase de Blasio’s top aides used repeatedly in 2014. “He is willing to take punches,” they’d say, “but he will keep moving forward.”

The template was established last January, when de Blasio went to Albany in pursuit of prekindergarten expansion and a tax increase on the rich. For months, the mayor absorbed blows from Governor Andrew Cuomo. He eventually gave up on the tax boost, but de Blasio never took the bait, avoiding a public feud with Cuomo. The reward was $300 million in cash and the preservation of a functional relationship with the governor. The phrase was prominent again in November, after de Blasio’s failed attempt to elect a Democratic majority in the State Senate: He might have lost one round, but he would stay in the ring for the full bout.

After 20 years of being led by aggressive-aggressive types, New York now has a passive-aggressive mayor. Some of de Blasio’s collegial style is philosophical, some of it strategically pragmatic. The mayor likes to say he won with a “mandate,” and it’s true he dispatched Christine Quinn decisively and Joe Lhota even more easily. But de Blasio understands that winning the pivotal Democratic primary with only 260,000 votes gave him an underwhelming landslide. So though the mayor’s aides talk about “multiplying” his base of support beyond the black, Latino, and liberal whites who made up his winning coalition, the administration knows it has to pay special attention to delivering for his core supporters. That means following through not just on the particulars of de Blasio’s income-inequality platform but on the promise that he’d be inclusive — hiring an administration as diverse as the citizenry and reaching out to a broader range of community groups.

De Blasio’s preference for collaboration and consensus is as much personal as political. Chirlane McCray once described to me how her husband’s belief in the importance of community is rooted in his experiences as a child in Cambridge, Massachusetts, particularly after his father’s descent into alcoholism. “His mother and her sisters were very socially and civically engaged,” McCray said. “That was a very strong influence on him.”

These days, the mayor’s senior deputies are quick to emphasize that de Blasio is a decisive boss, citing his relentless push to prepare for the arrival of Ebola as an example. “He’s very engaged, open, communal, and consensual, and all that,” says Tony Shorris, who manages the city government’s day-to-day operations. “There’s the old saying: ‘If you want to go fast, you go alone. If you want to go far, you go together.’ We’re fans of going together. But at the end of the day he’s going to make the call.”

In some ways, de Blasio is fulfilling a campaign promise. After three terms of Bloomberg autocracy, he’s bringing small-d democracy back to city government. But by elevating the importance of a host of other actors, from Bratton to McCray to labor-union leaders to Al Sharpton, de Blasio often diminishes his primacy. And the mayor’s willingness to recede from the action when under attack dilutes his own authority, making it harder for him to stand up to bullies, whether they’re leading charter schools or police unions.

Pat Lynch’s ugly words blaming the mayor for the deaths of Liu and Ramos were still fresh as de Blasio and his top advisers talked late Saturday night and early Sunday morning, on the weekend before Christmas, figuring out how to respond. What de Blasio decided was that he wouldn’t — not directly, anyway. Instead of engaging the police-union boss, the mayor would stick to a three-part plan: occupy the moral high ground by talking about honoring the families of the murdered cops and avoiding political fights, empower “responsible” voices to echo de Blasio’s message, and isolate the “bad actors.” The plan went into effect hours later at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, with de Blasio and McCray in the first pew listening to Cardinal Timothy Dolan’s plea for peace and understanding, and the mayor stuck to it diligently for two weeks.

It seemed a smart tactical choice, especially when the force essentially went on strike, a dangerous expression of the rank and file’s anger at the mayor. Yet all the righteous op-eds ripping the cop slowdown and praising de Blasio’s calm are missing one crucial part of the dynamic: Many cops won’t believe de Blasio is willing to stand up for them until he stands up to them. The mayor doesn’t need to rant, Rudy Giuliani style. But plenty of officers are still waiting to see whether de Blasio has the spine to confront the union’s challenge directly, instead of trying to pacify cops with new tablets and smartphones.

Meanwhile, de Blasio has been amazingly ineffective at changing the subject, even with all of City Hall’s resources at his disposal. Now Andrew Cuomo is looming. At his father’s funeral last week, the governor vowed to step in to heal the conflict. If he follows through, it could bail out his sometime-friend the mayor. But the move would also be a reminder that de Blasio’s conflict-avoidance strategy has its limitations; it might yield productive compromise, but it opens up turf for other players, including his enemies, and leaves the mayor looking weak. Last year, after talking tough about forcing charter schools to pay rent, de Blasio showed no appetite for taking on the movement’s noisiest leader, Eva Moskowitz. She will be back looking for more money and space in 2015. De Blasio’s accommodationist streak could also hurt him in upcoming fights over rent-control laws and mayoral control of the public schools, both up for renewal this year. And City Council members are pushing legislation to criminalize chokeholds and to require that cops obtain consent for warrantless searches — proposals that could further complicate the mayor’s efforts to reform the NYPD.

Bill de Blasio talks of creating not just a more progressive city but a more unified one. Yet after two decades of hard-asses in City Hall, one year of a softer mayoral touch has produced a city that’s more, not less, divided. Taking punches in the service of winning the larger fight might turn out to be craftily brilliant, as long as you don’t get knocked out in the process.

*This article appears in the January 12, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.