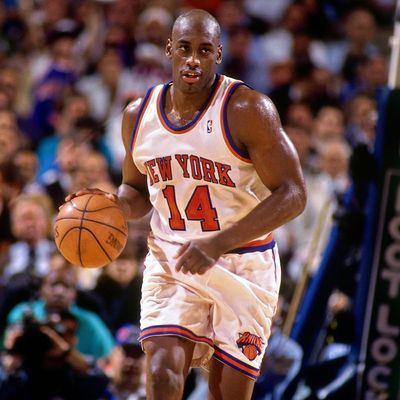

Anthony Mason passed away on February 28, 2015 after suffering a serious heart attack several weeks earlier. In honor of what Mase meant to the Knicks, read this 1994 New York profile.

The doors of his home are flung open, and you are told to remove your shoes. You are led down the lengthy white-plush-carpeted hall and shown a seat on the massive black leather couch. You are permitted to sit quietly or cue up a video from the host’s exhaustive and rigorously alphabetized collection of horror, sci-fi, and kung fu pictures, which features the (nearly) complete works of Bruce Lee, Godzilla, and Hong Kong action director John Woo, a particular favorite. You are not, however, to move around.

This is made abundantly clear by the centerpiece of the room, two giant samurai swords set on an ornate holder, the base of which accommodates an electronic running-type machine programmed to continually repeat, in red letters, SIT DOWN AND DON’T TOUCH SHIT. The master of the house will be with you shortly. He’s vacuuming.

“I don’t like a mess,” says Anthony Mason, the fearsome and funky 28-year-old forward for the New York Knicks, pushing the Hoover stand-up about the White Plains condo he sometimes shares with his girlfriend, Latifa, and their 2-year-old son, Antoine. He moved in only a month ago, so he hasn’t had time to take the tags off the couch. Likewise, the arcade room has an unfinished look, containing a single video game, NBA Jam Tournament Edition (“the one with me on it”). The “shoe room,” however, is well stocked, filled with several dozen pairs of the player’s size 15s, mostly Adidas, the company that has plastered many a subway station with ominous depictions of the six-foot-eight, 258-pound sixth man in mid-yowl, an essential ingredient of Mase’s “in your face” act.

“Cleanliness is next to godliness,” Mase mutters with offhanded irony as he bends his muscled frame over the glass table he is scrubbing with Windex. He stops cleaning only when he hears the door open and his mother, Mary Mason, walks in.

Mrs. Mason — or “Mom,” as she is universally known — is slightly jostled. Her new Mercedes (Mase has the same one) just ran backward down a hill while “in P,” says Mom, who until quite recently found herself using the New York City transit system to get to her job as a garment-center bookkeeper and back again to the modest southeast Queens apartment where she and Anthony, her only child, used to live. “You’d figure they’d make them better for all that money,” she says of the Mercedes. She’s a friendly, outgoing soul who, thanks to her son’s recent success in busting up the Derrick Colemans and Horace Grants of the world, no longer has to work, which gives her extra time to attend Knicks home games. She hasn’t missed “but a one” in the three years since Mase has been with the team.

“Pudding, you cleaned up nice,” Mom exclaims to her beaming son, squeezing his outsize arm. “Anthony is such a good boy. He always kept his room in order.”

Hoop, there it is: Anthony Mason — inscriber of semi-cryptic slogans such as DOGG POUND into the side of his huge, otherwise shaved skull and candidate for man most likely to make Mike Tyson’s palms sweat in a dark alley — is a mama’s boy.

“Anthony’s what I’d call an oxymoron,” says Pat Riley. “He defies expectations.” During the pair’s respective tenures with the team, the Knicks coach has served as both Mason’s champion and his nemesis. “As a player you look at Mase’s size and court demeanor and think he’s a blue-collar banger and he is, but he’s also very nimble, can outrun people, and has superior ball-handling skills. He’s deft, almost cute. There’s a bundle of contradictions about him. He’s versatile, unique in that way.”

Then Riley stops in mid-hagiography, forms his bituminous-eyed John Carradine half-smile, and adds, “Maybe too unique for his own good.”

Either way, Anthony Mason, unique oxymoron, figures to be a key Sisyphean broad-back in the current effort to keep the Knickerbocker stone from rolling down the mountaintop it very nearly ascended last year. The news out of preseason and the first eight games, whether about Patrick Ewing’s knee, or Charles Oakley’s toe, or Charles Smith’s penchant for the dumb foul, has been Jess than enticing. Even the local beat writers have been picking Indiana or Orlando to win the Eastern Conference.

This naysaying is no problem for Mase, however. Fond of breaking-and-entering metaphors, he says if the “window of opportunity” for another championship is closing, “we will just have to crash right through the plate glass, won’t we?”

No idle talk, coming from the Mase man. Probably the most popular player with the Garden crowd — which never fails to get guttural in appreciation of his jukey meldof heartfelt Queens homeboy flamboyance and locksmith defense — Mason knows how to play under less than perfect conditions. An inch from being an ex-Knick after his controversial suspension by Riley at the end of the regular season (more on this later), Mase singlehandedly kept the team in the sweatbox Chicago playoff series, laying some major smashmouth on pouty Scottie Pippen. In the finals, seemingly thrown into the middle as cannon fodder for Houston’s seven-foot Hakeem Olajuwon, Mase battled the sublime Nigerian to a standstill, something the strangely erratic and suddenly bashful Knicks center Patrick Ewing could not do. Hakeem, philosopher that he is, took note, sitting in the locker room rubbing his bruised arm and commenting, “Mason … small guy, but likes to bang.”

That performance and the potentially decaying infrastructure of the Knick front line led many observers to the conclusion that this is Mase time. Which should have worked smoothly, financially speaking, since Mase is in the last year of a contract worth $1.3 million per year-a sum that cries out for a serious upgrade. But things never quite work smoothly in Mase’s often monkey-wrenched world. The recent NBA/Player’s Union settlement create an unexpected deadline for teams to sign players in Mase’s contract category. Mason’s demands, reportedly as high as $18 mil for the next five years, were deemed “difficult” by Knick management. A new deal was not forthcoming, the upshot being that Mase, free-agent-to-be, will be forced to play the year “dogged by uncertainty.” But then again, Mase notes ruefylly, “uncertainty is nothing new for me.”

All things considered, however, life is pretty sweet for Anthony Mason, pride of South Ozone Park and Linden Boulevard. He’s getting paid some $16,000 a regular-season game to be a star player on the big-league basketball team in his hometown. Damn, he even got mentioned (for having “correct” hair) in a Beastie Boys song, right alongside Kool Moe Dee, AI Goldstein, the Buddha, and other local heroes.

This is a sight better that the way it was in 1988, when Mase, then 22, spent a good portion of the year holed up in an Istanbul hotel room watching kung fu movies with Mom and his friend Tom.

“Turkey was strange,” Mase says with a slight shiver remembering his seven-month sojourn in rinky-dink pro basketball leagues in Asia Minor. “There ain’t too many dark-skinned people there — not ones that look like me, anyways.” The food wasn’t anything to rave over either. “Even the burgers tasted different. I do not like to criticize another’s culture, but I had to frown at some of the squirrelly things those Turks were slurping up.”

How Anthony Mason of Queens, New York, came to shoot baskets in Istanbul, Turkey; Caracas, Venezuela; and several other remote outposts is still another addendum to the twists of the game so tellingly detailed in the current documentary Hoop Dreams. It is a tale of resisted marginalization and one exceedingly big dude’s absolute refusal to take no for an answer.

Always a late bloomer, Mase didn’t play a serious game of organized basketball until he was a junior in high school. Growing up with Mom in Passaic, New Jersey, Mase was a painfully shy kid who often came home in tears because his classmates said his feet were too big. A repeat winner of spelling bees in grammar school (he claims to have a photographic memory), Mase first dreamed of becoming a “mean, black left-hand pitcher with a nasty hook and a scowl” for the Yankees.

As it was, he wound up making the football team, but he never got to play a single varsity game because Mom moved over to Laurelton, Queens, before the season started. Mase was crushed to find that the local high school, Springfield Gardens, had no football team. A couple of days latetMason, a mere six foot-five, 165-pound sylph of his current self, seized what he now says was the “last option” and walked into the office of gym teacher Kenny Fiedler asking for a basketball tryout.

“To tell you the truth, he wasn’t that good a player then. He was raw. But very coachable,” says Fiedler, a career PE teacher and coach in city schools whom Mase, his massive eyes suddenly welling up, calls “my dad … the father I never had.” A self-confessed “classic Queens basketball junkie,” Fiedler, whose two sons (one of whom is the backup quarterback of the Philadelphia Eagles) remain tight with Mase, says, “Anthony was special because he came out of nowhere, was very, very determined, and he got better so fast. It was like there was a button there waiting to be pushed. Mason not only would up making the team but also hit several key baskets as Springfield Gardens, a deep underdog, won the always phantasmagoric city championship that year (1983). It is a victory that Mase still says “can’t be topped, at least until we win the NBA title.”

But when you’re a city game player, what happens on nicely buffed indoor wood courts doesn’t tell half the story. You’ve got to charge the yard, and Mase’s yard was Baisley Park, over by the intersection of Baisley and Merrick Boulevards. That’s where all the essential southeast Queens helicoptering got done. But this being the mid-eighties, funky facials and shoot-around games of H-O-R-S-E often took a backseat to full-court gambling extravaganzas sponsored by the likes of crack-posse gangsters Fat Cat Nichols and Pappy Mason. With thousands of posse dollars riding on the outcome, these contests often took on an added seriousness, most graphically when a referee who saw a certain play the wrong way wound up murdered.

“Now, that’s some real pressure,” says Mase, who played in several of those games. “They were the big, bad men,” Mason says of the now incarcerated Nichols and Mason, “but at least when they were on the street you knew what time it was. After they went insane and killed that cop [rookie patrolman Edward Byrne], things got crazier because everyone was looking for a piece of the pie.”

This neighborhood history remains fascinating to Mase. When he retires, he says with a smile, he plans on going into criminal justice, “except I ain’t decided what side yet.” But even if he still can tick off the names of the Supreme Team, one of the major crack-dealing posses, there was little chance that the teenage Anthony Mason would fall into the gangster life. Mom saw to that.

“Let me tell you, my son and I were close. As close as we could be,” Mary Mason says now. “I told him that I didn’t work no two jobs, sit there reading you a book every night while you took a bath, so you could grow up to be one of those posses or some no-pork-eating Five Percenter. I said, ‘Before you go off and kill your self on drugs, I’ll kill you myself.’ I’ll call up the 103rd Precinct and tell them to get in their cars, put on that siren, and get right over to my house because I’m about to kill my son! I love him, but I got to kill him! He’s giving me no choice. You got to get over here and stop me! … And you know what? It worked. Because Anthony never fooled with any of that garbage.”

Mase still cringes at the specter of his diminutive 60-year-old mother marching over to Baisley Park to fetch him out of three-on-three games because he stayed out past 9 P.M. But he knew he better listen, and he did. He promised he’d make the honor roll at Springfield Gardens and did. He got over 1,000 on his SATs and had an 80 average. With the city-championship crown in hand, Mase figured numerous leisure-suit-wearing recruiters bearing scholarships and other sub-rosa goodies a la Blue Chips would beat a deep path down Merrick Boulevard to his door.

It didn’t work out that way. Mason, not yet 17, ended up at Tennessee State, a small college in Nashville, which doesn’t mean he spent much time at the Grand Ole Opry — “Us fellas didn’t go over to that side of town.” He did stop being skinny, however. “Coach Fiedler told me to drop and do 50 push-ups every time I’m watching TV and a commercial comes on. When I was in Tennessee, I watched a lot of television.”

In that way Mase the mobile mountain came into being. An impressive thing it is to see, too: A. M., his great thighs pumping, a big cartoon of a man who somehow approaches sleek and silent, hovercrafting the lane as if he were some stealth-bombing Zamboni, and then bam! — another unsuspecting Tom Gugliotta or Hot Rod Williams is flattened, left to peer up through tweeting birds at the retreat of Mase’s sneaker tread. The Mason torso is no less arresting in the locker room — his butt halfway out to Hempstead, the buns bugged out like a pair of exploding medicine balls.

Mase got massive at Tennessee State all right, and even if he was calling Mom all the time to say he wanted to come home, he also got good. He broke in by dunking over Georgetown star Patrick Ewing, now a teammate (Ewing claims not to remem ber the incident). By his senior year he was averaging 28 points a game, doing it from all over, including finishing among the leaders in the country in three-point shooting.

In 1988, Mason got drafted in the third round by the Portland Trailblazers. “We were hoping he’d get cut right away,” says Kenny Fiedler, who says Mase was calling him “four to five times a night.” “It wasn’t a good situation for him. He never had a chance. Jerome Kersey and Mark Bryant were ahead of Anthony. But they didn’t cut him. They put him on the injured list. Anthony was calling me, saying, ‘But, Dad, I ain’t hurt, why don’t they let me play?’ He thought it was like purgatory.”

Fiedler was friendly with Willis Reed, who was then the coach of the Nets. Reed liked Mason and managed to get him from Portland on waivers. Things went well in Jersey; Mason played well, made the roster, got minutes. But the the Nets kicked Reed upstairs and brought in the crusty Bill Fitch to coach. Fitch had little use for a seeming bad hat like Mason. It wasn’t long before Fiedler received a call from a sobbing Mase saying, “Dad, I got cut.”

Then the odyssey began. Mase says he doesn’t want to think about how he got to Turkey other than that he wanted to play ball and it didn’t matter that everyone in the neighborhood said, “You going where?” Mom’s recollection is more specific. “Some slick asses out of Chicago found Anthony in a hotel lobby, gave him money, and promised him a car. We had to call up’ Congressman [Floyd] Flake’s office and get the passport because they said he had to leave right away. Well, the car turned out to be a rental, which Anthony had to pay the bills for …. They were just body snatchers looking for an innocent boy to send overseas.”

“A little bit of the blue, it was,” Mase, 22 at the time, says of his Ottoman interlude, for which he got about $80,000. “All I did was practice, play, and stay in the hotel room …. People would follow me down the street. Then I’d go into the hotel, go to sleep, get up the next morning, go out, and there’d be the same person still staring at me.”

Venezuela, where Mase spent part of 1989 and 1990, was a lot better: “Food was great. It wasn’t Muslim, so there were plenty of women. We played in a town by the beach, and I’m real good at picking up languages, especially Spanish. So it was pretty much of a party.”

Characteristically, Mase compartmentalizes these global peregrinations in terms of what each stop contributed to his decidedly idiosyncratic game: “In Turkey, everyone could shoot. Even the seven-foot Frankensteins, they could hit long-range shots. But someone’d have to be dead before they’d call a foul. You had to bother those shooters, so I learned to get more physical. … In Venezuela, though, they’d go nuts if you touched anyone, so I learned to play defense with my feet. It improved my quickness.” As for his fabulous “handle,” the kinky rhythm that never fails to rock the Garden, Mase already had that, from Baisley Park.

Reviewing his b-ball hero’s journey, which was not unlike that of his best pal, John Starks, but so different from one taken by first-round draft picks who demand $100 million before they bounce ball one, Mase says, “I think it helped to make me a man. Self-reliance got to come into it.”

The strange thing is, Mase claims he wasn’t even thinking about the NBA when he finally got his chance. Scoring points by the bushel for the Long Island Surf in the obscure United States Basketball League, Mase wanted merely to get to Italy, “where they pay real money, $400,000 and more.” But then scout Fuzzy Levane and Knicks G.M. Ernie Grunfeld, the former Forest Hills flash, caught Mason’s kamikaze act and brought him into camp. It wasn’t long after that the newly hired Pat Riley, in from L.A. to save New York, was raving about “this guy Mason,” who was the hardest worker in camp and just the sort of kick-ass player he’d need if he was to turn the Knicks into winners.

Well, Mase and I had been hanging a bit, so we thought we might play a spot of one-on one… Yeah, right. One thing: Don’t bother to check the eyes. Maybe Mase has these big doggy lamps when he’s on defense, or just sitting around jawboning, but when he’s handling, those orbs slit up tiny, not giving any thing away. Down below, he’s employing,his shell game of a crossover dribble, challenging you to take the pill. Swatting it with your hand is not going to work, so you might as well dive, fling your entire body toward the bouncing ball. But Mase is quick, he gets his knee up to meet your chest, and then you’re in the second row of bleachers. To which Mase will say, “You ain’t getting that call.”

This is Mase’s way of getting acquainted. He’s a tactile kind of guy. You can tell he thinks you’re okay when he starts punching you in the arm. Driving his Mercedes 50 miles per hour around the hairpins of an indoor parking lot, he’ll reach over grab your knee, and squeeze till you squeak. “What happened to the muscles you’re supposed to have in that leg?” he asks. “Don’t you work out?”

Other than this black-and-blue factor, hanging out with Mase is no particular problem. You want to slide with him to the video store, get into a one-up thing about how many lines you can remember from Enter the Dragon — hey, bring it on. Today, though, is haircut day.

Typically, a Mase haircut can begin at any hour, often as the power forward tools about in his Benz. He’ll be idly running the palm of his massive hand over the dome of his expansive head and feel: fuzz!

“I hate fuzz,” Mase snarls, punching the button to open the cellular panel. He works the speed dial. “Freddie!” Mase screams. From out of the clatter on the other end of the line comes a Hispanic-inflected woman’s voice. “Freddie not here! Who’s this?”

“Mason! Tell Freddie … I’m coming!” Then, it’s pedal to the metal, down the Hutchinson River Parkway, across the White stone Bridge, the Grand Central, a blur down Parsons Boulevard to Hillside Avenue, where — among the Guyanese roti bakeries, Jamaican ram’s-head-soup purveyors, and Sri Chin may’s American mission — the Masemobile slams to a stop in front of Cutty’s Hair Studio.

Alfredo Avila of Cartagena, Colombia, proprietor of the chartreuse-and-lavender-intensive Cutty’s, serves as hair consultant to several outerborough-bred NBA stars as well as to many rappers both “jailed and out.” But Mason is his favorite client. A friend from the Springfield Gardens days, Freddie has been “writing” razor-buzz graffiti on Mase’s ample noggin for years, adding a florid touch to the Madison Square Garden foul lane as Mase elbows the guy next to him. Occasionally Freddie is feeling abstract, such as with his New York skyline series back in 1992–1993. But for special occasions, such as last year’s finals, the more somber, metaphysical IN GOD’S HANDS seemed in order. These semiological notations can be altered quite often, for as Mase points out, “My hair grows fast.”

“Cutting is my art,” Freddie, a sweetfaced chocolate-brown man, says with no small emotion. “And Anthony, he’s like … my canvas.” For Mase, strutting around in front of 20,000 people wearing Freddie’s art is a homeboy imperative. He gives his barber full freedom. Sometimes he doesn’t even bother to ask what’s about to be etched into the side of his head. “I trust him,” Mase says of Freddie. “Until he fucks up, that is.”

As for today’s sitting, Freddie is faced with a dilemma. It has come to him, with the season imminent, that Mase’s head should read, ONCE AGAIN IT’S ON. But this is too much phraseology even for a dome of Mason’s dimension. Scouting the head/canvas with his thumb, John Nagy-style, Freddie decides to edit down to AGAIN IT’S ON. The cut takes about five minutes. It looks great, script relieved on skull like 3-D, right down to the apostrophe. “Cool,” Mase says, bending for a quick look in the mirror.

A moment later Mase stands astride the bustling intersection of Parsons and Hillside, a colossal inner-city icon in his Nike hat, Giants football jacket, Knicks pants, Adidas shirt, SkyPager beeper at the waist. “Seems like I spent about half my life on corners like this, freezing to death, waiting for the damn Q-10,” he remarks, squinting into the late-afternoon drizzle. A few baggy-pants-wearing kids come across the street from Hillcrest High School, screaming, “In your face, Mase, in your face.” From the doorway of the sari store, a well-dressed Indian gentleman says, “Good luck in this year, sir. My son cheers for you.” Some Rastafarians saunter by, with bloodshot eyes and Haile Selassie jackets. “Ire, Mase, mon, we betting on you, mon,” they intone. A turbaned man from the Kabul grocery comes out to gawk.

Mase acknowledges his ethnically far-flung public with curt nods and small smiles. For all his extravagant self-presentation on the hardwood, he’s not particularly outgoing off the court. Even though he’s been known to show up at Baisley Park at four in the morning to shoot baskets, Mason is reluctant to play the returning hero. Uneasily shifting his feet over old stomping ground, he’s looking to split.

“What do you want to do now,” he says by way of an exit line, “go over by Linden, see who’s shooting at who?”

“I know now I’m Anthony Mason, and I gotta be Anthony Mason,” he says, referring to himself for the first time in the athletic third person. “But that ain’t me. I’m more serious than that.”

This was clear enough just moments before, back in Cutty’s when Mase leaned over and, apropos of nothing, said, “Are you a Christian?”

“Uh … no,” I answered.

Raised a churchgoing Baptist by Mom, Mase has “no time for hypocrites who think believing something is about not cursing and wearing certain clothes.” Mase says his relationship with the Lord is an intense private affair. “Don’t you believe in God? he asked. I said I did.

“How can you say you believe in God if you ain’t a Christian?”

My reply may have seemed a bit equivocal considering the directness of the question and the fact that you have to yell to be heard in Cutty’s once they’ve got the box cranked up real good. Basically, I said I believed there were many different methods and beliefs that sought to come to grips with “this enormous idea.”

Mason stared deep into my eyes. If that’s the way Mase looks when he’s trying to push Karl Malone off the blocks, then it’s pretty remarkable the Mailman doesn’t run right out of the building. With chilling finality, Masc says: “It’s not just an idea to me.”

Likely it is this inviolate sense of the moral bottom line that informed Mase’s behavior during his infamous clash with coach Pat Riley at the end of last season, a dustup that can only be described as a back-page Passion play. On paper it was a walkover: Mase, funky-headed ex-minor-leaguer with a reputation for being a brute on the court and a sulker off it, the Flavor Flav of the cheap seats, but just the sort of scary Negro to raise the hackles of WFAN callers … vs. … the Great and Powerful Riles, Gordon Gekko-coiffed Lord of the Rings, four-time champ, coach of the eighties and maybe the nineties. Off that stacked deck, who could have predicted the competitive matchup that would ensue?

To recap: Last year with the Eastern Conference title on the line, Riley elected not to play Mase in the second half of the all important Atlanta game, using the largely ineffectual Charles Smith instead. Mase, who’d announced himself “way up” for what he called “the biggest game of the year,” brooded visibly at the end of the bench during this banishment, at one point declining to join a team huddle.

After the game (which the Knicks lost, 87-84), hearing that Riley had gone with Smith because “he’s our best offensive forward,” the “very” ticked Mase told reporters, “That’s his [Riley’s) opinion … He has his opinion and we have ours.” Mason then went on at length, pedantically detailing his particular and highly self-aggrandizing definition of “offense,” in case Riley was unaware of the concept’s fine points. The coach, not rioted for gracefully accepting such lectures from his minions, especially ex-CBA skells, and irate at what he took to be one of his players making “derogatory remarks” about a teammate, kicked Mase off the club “indefinitely,” citing the foward’s conduct as “detrimental.”

That should have been that, except Mase, continuing to claim innocence, appeared in the stands at the very next game, against Philadelphia, circumnavigating the Garden’s upper level (where the real Mase fans would sit if they could afford to get in), extending high-fives all around and managing to get his disobedient self on many TV screens. Taking this as an unthinkable dis (how else could he have taken it?), Riley became exceedingly steamed.

A couple of days later, when Mase, either oblivious of his coach’s mind-set or simply tweaking the envelope another inch, showed up to work out at the team’s SUNY-Purchase practice facility. Hearing of Mason’s presence, the famously unflappable Riley got him on the phone and started screaming, “Don’t you get it? You’re banned! You’re barred! You’re not part of the organization!” Taking the entire episode as a cosmic slight against his commitment to the game, Mase went home.

At this point, matters became really serious, since, according to Mason’s agent, Don Cronson, who has been a representative for 22 years and “never been involved in anything as volatile as this,” it had become very touch and go as to whether Mason would actually be put back on the playoff roster by the deadline. For Anthony not to be in the playoffs would have caused his career very serious damage,” Cronson says, “and by that I think you can say it would have caused his life very serious damage.”

Eventually Mason and Riley reached some sort of détente. Mason was added to the playoff roster “one minute” before the deadline, according to Riley. It turned out to be quite a good thing for the Knicks, as anyone watching the games could see. This included Pat Riley, who, after the second Chicago game, said, “Without Mase tonight, we lose.”

Well and good, but there is an alternative take on Riley’s motives for suspending Mason that has been whispered about in Knickworld. To get it, you’ve got to go back a few days to the game before, a depressing performance against Charlotte.

“I have failed miserably,” Riley said after that loss, to the quiet amazement of the assembled writers, who had never before seen the emotionally opaque coach look this rattled. “I’ve got to think about it. I’ve got to go home, go into a room, turn the lights off, and think about.

Of course, it is impossible to guess what Riley thought once he got back in his room, the lights off. But as George Vecsey of the Times would point out, there is a section in Riley’s best-selling motivational treatise, The Winner Within, in which the Knicks coach explains his “temporary insanity” theory of corporate crisis management. As quoted in Vecsey’s column, this strangely Nixonian strategy is defined by Riley as “the art of being angry at the right time, to the right degree, with the right people … It requires plenty of advanced thought, a real and focused mental plan — not an emotionally driven monologue.” To achieve the desired effect, Riley concludes, a “dose of T.l. demands a rapid follow-up of compassion.”

Perhaps it is too delicious to think of a legendary winner like Pat Riley seeking solace in his own how-to book, but the coach, whose rep and success with the undertalented Knicks have granted him near press immunity, was taking an unaccustomed grilling from the media. After the Charlotte game, Pete Vecsey, George’s nastier brother and unquestioned savant of hoop hipsterism, wrote in the Post: “It took the Lakers nine seasons to stop responding to Riley. New York lifestyle is faster, it took the Knicks less than three … Riley must be overcome by losing. He should be giving Anthony Mason minutes belonging to Charles Smith, not the opposite.”

At this point, followers of the temporary-insanity theory find it not impossible to imagine the Knicks coach getting a load of whatever crap Anthony Mason had scribbled on the side of his head and going into rewrite mode. Something like RIGHT PERSON or perhaps FALL GUY.

If Riley was just looking for someone to discipline in an effort to shake the Knicks out of the doldrums, the notably emotional Mase would have been the logical guy. “The buttons were there to be pushed,” says a reporter. And since the Knicks won the next three games, you could say the ploy, if it was that, worked.

To a degree. The final segment of the temporary-insanity theory did not take. The drearily paternal “dose of compassion” was short-circuited by Mason’s refusal to accept his medicine quietly. Call his noncompliance just part of what Riley has termed “a broader pattern of disrespect in this league.” Or was it the act of someone who’d followed his ethic to the funky corners of the world and now-acting on a however-dementedly-arrived-at point of honor-believed this was the place to make a stand?

Coming into this season, things were supposed to be more or less hunky-dory. Pat Riley, who actually evinces no small affection for Mase and his roundabout journey, dismisses the whole thing as “a family matter which was settled in the family.” Scratch the surface ever so slightly, though, and Riley is less relaxed. “People say I’m arbitrary,” Riley says with gathering heat, “but I’m not arbitrary. I think I’m fair. But if a player is going to befriend someone in the media, say, and try to stick a knife in my back, well, that’s his business, but he can expect to be probed; he can expect to be dealt with.”

The kicker in this is, of course, Mase and his unsigned contract, which created the usual back-page fire storm two weeks ago. Ian O’Connor in the News, saying Mase was “too much of their soul and too much of [the Knicks’] city,” called on the Knicks to “give Mason the money.” Jay Greenberg’s Post column was headlined MASE NOT WORTH $3M PER. The fact that the Knicks rushed to come to terms with championship-blowing John Starks before the deadline only goosed the situation. In the end, however, it came down to what Cronson says “it always comes down to: money.” But this being Anthony Mason things are never that simple. Riley was quoted as saying, “Some things happened last year that made us think twice … If you’re going to live your life with somebody, you want to make sure you’re right and they’re right.”

Although described by witnesses as “more” ticked than during the suspension incident, Mase struggled man fully to avoid “saying the bad thing.” Amid protestations of being “unappreciated,” he did, however, offer this critique on authority: “If something is done, you punish your kid, then you take him off punishment and forget about it. You don’t keep reminding him about it or keep it in your mind, or otherwise he should stay on punishment.”

A couple of days later after mashing his chest into Shaquille O’Neal for a quarter and a half, Mase is in better humor regarding his contractlessness. Celebrating the win over Orlando in a raucous locker room, placing his huge hand over his eyes, he jokes, “Oh, those mothers, how they done me! It’s horrible. I can’t even talk about it.” Then, he says that even though he may be “hurt, angered, and frustrated,” he has “willed” this most recent incident out of his mind, dedicating himself only to winning.

Beyond this, Mase says, even if he sometimes thinks about “looking for some pillow” when Riley begins one of his aphorism-laden motivational speeches, “Pat and I are cool. … We understand each other.” Mase, who will no doubt go to his grave believing the Knicks would have won the NBA title if Riley had played him against Atlanta, remains unrepentant. “All I said about Pat was … that’s his opinion … well, that’s still his opinion. Mason don’t talk in tongues … What my mother taught me was to say what you mean, and if you really believe it, don’t back down. I follow that. Life goes on.”

So it does. A couple of nights later, incongruously enough, Mase is standing under a massive crystal chandelier at Leonard’s of Great Neck, bar mitzvah capital of the North Shore. He’s here to accept the second annual Achievement Award “for commitment to the southeast Queens community” from CUNY’s York College Foundation-Mason is setting up a scholarship earmarked for black men who maintain a high-school average of 85. The “crew”-Mom, Aunt Juanita, Cousin Carol, girlfriend Latifa, Kenny Fiedler, Don Cronson, homeboys Thomas and A. J., everyone dressed to the nines, beam as Mase, a heck of a lot more nervous than he ever appears before a basketball game, gets up to make his speech. After some jokes, Mase says this is a pretty big honor because “Queens is my home and I have pride in it.” Education can be “a salvation,” he says, something he knows firsthand because “a lot of brilliant minds” who didn’t go to school wound up “in bad situations.” It’s a pretty moving speech, all things considered. And Mase, who gets a huge ovation, looks kind of choked up himself.

A couple of nights later, however, Mase is back in everyone’s face. After a seemingly endless game against the Washington Bullets, he’s railing about the new handchecking rules, which he takes as a personal affront. “It’s a damn humiliation, a sissy thing. Why don’t they put skirts on the players?” Mase whines with decided uncorrectness, standing in the locker room buck naked.

A moment later, in the hallway outside, dressed in his customary all-black, Mase raves on: “What’s next? You won’t even be able to look at the offensive player. They’ll make it a game for blind men.” But now Mom is there, along with Thomas and A. J. and Latifa and Antoine. “They’re taking all the respect out of things, Mom,” Mase whines.

“Ain’t your business, Pudding,” Mom says. “You just go out there and play your game.”

To which Mase, hanging his head, nods. “Okay, Mom.”