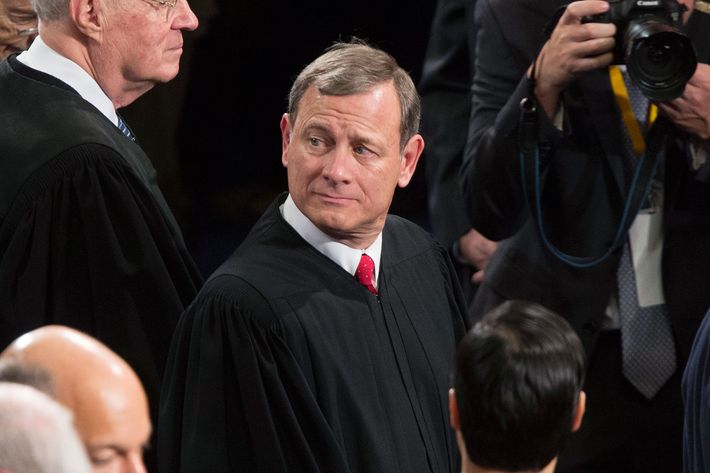

Update: On March 4, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments on King v. Burwell. The general view among court watchers is that Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Anthony Kennedy will be the swing votes in the case.

Next week, the Supreme Court hears a legal challenge to the Affordable Care Act that, if successful, would “cripple,” “destroy,” “gut,” (or any other violent term normally reserved for a Liam Neeson movie or a website aggregating John Oliver videos) the health-care law. Or so news coverage has told us.

The impression seems to have taken hold that the lawsuit, King v. Burwell, would do approximately the same level of damage to Obamacare as the previous Supreme Court challenge. It is true that, if successful, the lawsuit would pose a huge humanitarian setback to the sick and poor. But in the long run, its impact on the law would probably disappear. And in the short run, it threatens Obamacare’s opponents, not its advocates.

King v. Burwell alleges that, for the last five years, the Obama administration has illegally interpreted the law in a way contrary to what Congress wrote and intended. The law gives every state a chance to create its own health-care exchange, and if it fails to do so, the federal government steps in. Conservatives claim that the law does not provide tax credits for the federal exchanges, which are currently used by 36 states. The lack of tax credits would make the federal exchanges instantly dysfunctional.

The conservatives supporting the lawsuit claim this was Congress’s intent: Saddling states with dysfunctional exchanges was a punitive measure designed to coerce states into creating their own exchanges. The argument is utterly preposterous. Everybody involved in writing the law in Congress denied that this is true, denied it contemporaneously — as did its Republican opponents. Moreover, as a matter of legislative history and simple logic, when the federal government does design a program to coerce states into a certain choice, it announces the policy clearly rather than keeping it a total secret for years until discovered by fanatical haters of the law.

But assume for a moment that the lawsuit succeeds. (This is by no means a likely assumption, but we’ll get to that later.) What would happen? 11.4 million people would see their insurance markets implode very quickly, which would be awful. But what would happen after that is probably far less dire.

When people imagine the aftermath of a successful King lawsuit, they usually have in mind the 2012 case, which gave states the right to opt out of the law’s Medicaid expansion. That punched a large hole in Obamacare’s coverage expansion, allowing Republican-run states to deny coverage to their poorest citizens.

King would work differently. Remember, Obamacare did not take effect until 2014. That meant that Republicans were given the chance to shut down an expansion of coverage to people who weren’t due to receive it for a year and a half. Most beneficiaries were (and still are) unaware of its existence. While the hospitals that would lose profits because their potentially insured patients would now be uninsured may have been lobbying for Medicaid expansion, the potential beneficiaries themselves simply have no idea what their Republican elected representatives have done to them.

The King v. Burwell suit would strip coverage away from people who already have it. Citizens are far, far more likely to react to the loss of a benefit they already enjoy than a hypothetical one. (Social scientists call this well-established phenomenon “loss aversion.”) Loss aversion is probably the single most potent force holding up the welfare state, even when conservatives try to pare it back. In 2012, the Medicaid opt-out created zero already-existing victims, but King v. Burwell would create 11.5 million of them.

Additionally, the exchanges serve a more affluent class of beneficiaries. Medicaid helps the very poor, who are disproportionately likely to be racial minorities and also disproportionately likely not to vote. They are relatively easy for Republicans to ignore.

The exchanges sell insurance to the middle class. Now, many of those customers or their family members have serious health needs that make the unregulated insurance before Obamacare unaffordable, but their expensive medical needs are the only element separating them from traditional Republican constituencies. Destroying the exchanges would, as a result, wreak havoc with the lives of lots of people, like Erin Meredith, a Texan and fifth-generation Republican who hated Obamacare but found herself with an office-manager job that didn’t provide health care, then discovered that she has a rare and expensive medical condition. She found a subsidized (and, thus, affordable) insurance plan on Texas’s exchange. But if Texas pulls out of its exchange, she faces chaos or even ruin. “If they’re not going to participate in Obamacare,” Meredith told the Washington Post, “and I’m not going to have these financial benefits, which will force me to pay $220 a month for coverage, do you know if Greg Abbott, our governor, has any plan to offer something comparable?”

Republicans do not, in fact, have an alternative. The Party has never coalesced around a single alternative health-care plan with which all Republicans can identify, because the real-world trade-offs involved in writing a workable plan would force them to defend unpopular changes. And it is beginning to dawn on them that the pressure to alleviate the chaos that would result from the lawsuit would fall entirely on them. After all, the two most straightforward ways to repair the breach the lawsuit would open would be for Congress to pass a law clarifying that the federal exchanges will continue to provide tax credits, or for Republican-controlled states to create their own exchanges. Both those alternatives would be unacceptable to conservatives who refuse to negotiate over Obamacare in a way that recognizes its legitimacy. Destroying the law is the only outcome conservatives will accept.

Conservatives like Phil Gramm and National Review’s Ramesh Ponnuru have begun devising strategies for the GOP to escape what Gramm calls “powerful political pressure on Republican governors and legislators and force them to establish state exchanges.” But while they describe the conundrum facing their Party clearly enough, they grow hopelessly fanciful when laying out plans to escape it.

Gramm has proposed that Republicans agree to restore the tax credits only if Obama, in return, agrees to deregulate the insurance market. Gramm hopefully calls this the “freedom plan,” because it would allow healthy individuals the freedom to buy skimpy plans that don’t cover essential health benefits, and which exclude or charge prohibitively higher rates to people with a preexisting condition. By allowing insurers to skim off healthy customers, it would make insurance unaffordable to people with serious medical needs. As Gramm boasts, his plan “would put ObamaCare on the path to extinction.”

But this would require Republicans to tear down the most popular elements of the health-care law: the regulations prohibiting insurers from discriminating against people with preexisting conditions. (Indeed, this element is so popular, Republicans frequently propose to replicate it in their own hypothetical proposals.) Gramm further speculates, with even more implausible optimism, that Republicans could get six Senate Democrats to sign onto their plan. Why even one, let alone six, Democrats would support a plan that would — in his own words! — put Obamacare on the path to extinction, he does not explain.

All this is to say, Republicans are not going to have leverage to wrest concessions in return for un-wrecking Obamacare’s exchanges. They will simply find themselves recapitulating a form of hostage politics, where they demand policy concessions in return for sparing America widespread damage, and Obama simply insists they spare America, full stop. Hostage politics are not popular. Congressional Republicans can hold onto their stance of refusing to reopen the exchanges, but they will pay a significant price to do so.

In the short run, Congress will remain in a standoff because no amount of pressure is likely to be enough to budget the House to collaborate with the hated Obamacare. Then it will simply be a matter of peeling off governors and state legislatures, one by one. This will be a long, grueling process, beginning in the blue states, moving into the purple, and eventually the red ones. Two and a half years after the Supreme Court blew open the Medicaid hole in the law, the Republican boycott has slowly contracted. Republican states like North Dakota and Indiana have joined, and states like Alaska, Montana, and Wyoming may be soon to follow. The Deep South (where, unlike the plains and Mountain West, the poor are heavily black and thus less sympathetic) remains a holdout.

But it is far from certain, and not even likely, that the Deep South will continue to nurse its rabid Obamacare boycott, at the cost of imposing such a costly disadvantage on its own health-care markets five, ten, or 20 years later, long after Obama is gone. Even should many states maintain their Obamacare embargo, at some point, Democrats will regain a functional majority in Washington. Designing a health-care law that could appeal to all the industry stakeholders and cover its costs was a brutally hard political task that consumed decades. But given that Obamacare has been shown to work, simply patching up a Court-created hole would be easy, the sort of bill a Democratic administration would sign in its first week in office.

And all this in turn suggests that the Court may have little stomach to side with the challengers. Remember, John Roberts reportedly changed his mind about overturning the law completely in 2012, out of a concern that using a tendentious and partisan rationale to destroy a landmark government program would rob the court of its public legitimacy. The newest lawsuit not only rests on a far more tendentious (and even ludicrous) legal basis, it would achieve much less than its predecessor. Why should Roberts spend down his political capital to land a temporary, partial blow against Obamacare — at a heavy political price for the Republican Party, to boot? If we assume Roberts is following a political calculation, as both many conservatives and nearly all liberals now do, it is hard to see the percentage in denying the previous Obamacare challenge only to allow a more foolhardy one.