Ray Rice’s Redemption Campaign

“Man, they just don’t know who I am.”

One snowy evening this winter, I drove to see Ray Rice at his mother’s house in a quiet middle-class neighborhood in New Rochelle. Three cars were parked at the end of a curved driveway, including a 2015 BMW coupe, which Rice had provided along with the house. “Only the best,” said Janet, his mother, who wore a diamond-studded cross around her neck, another gift from her son.

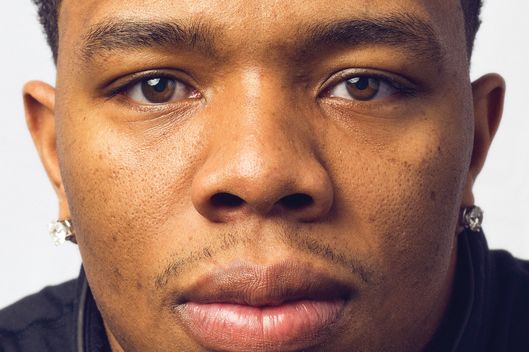

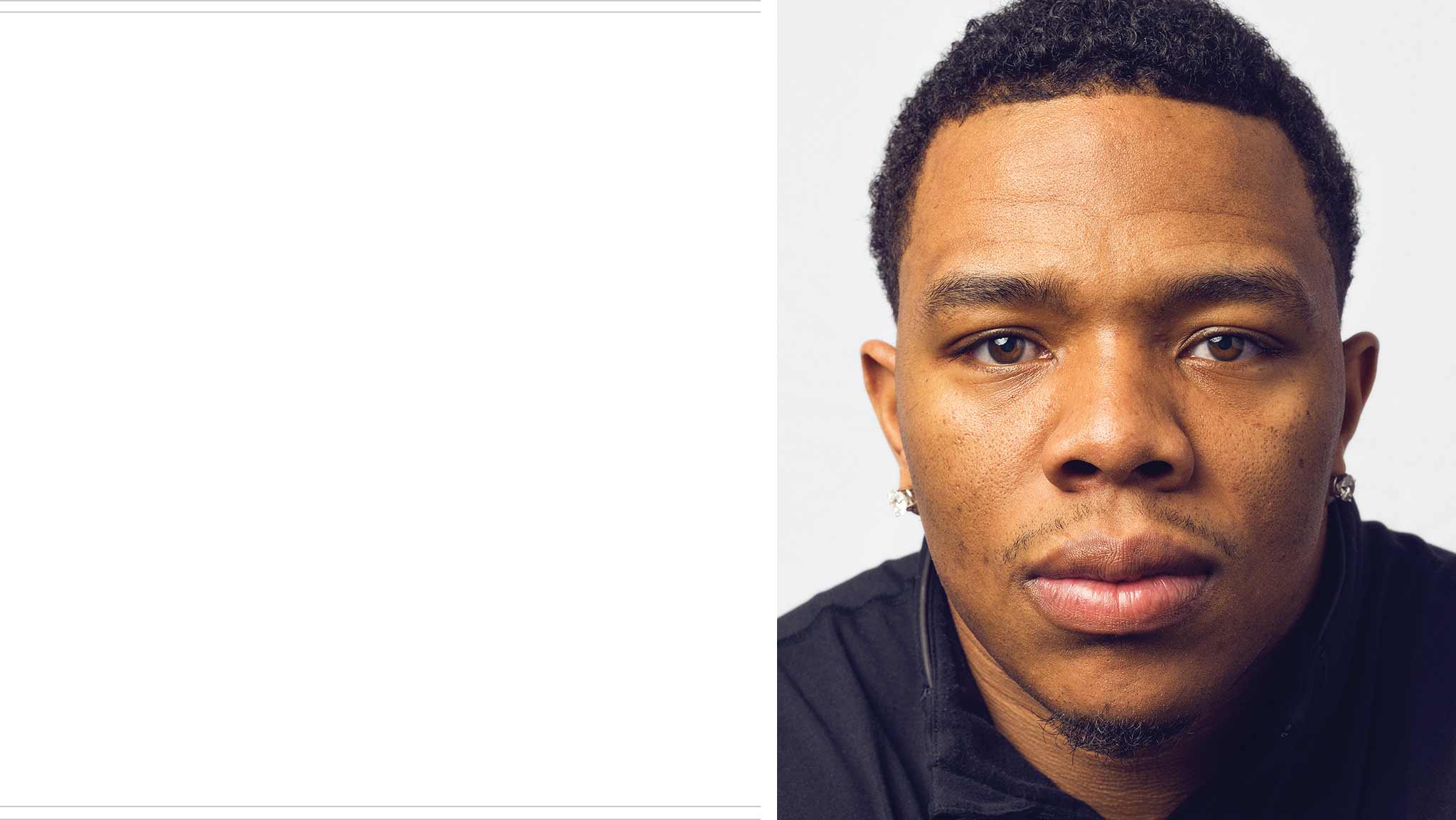

I was here to talk to Rice, a year into probably the swiftest and most decisive fall from grace for an American athlete since Michael Vick — or possibly Mike Tyson. Rice arrived a few minutes after me, and his entry was an event, his family gathering when they heard him at the door. For an NFL running back, Rice is strikingly unimposing. First, he’s small, five feet eight — the first time his mother-in-law met him, she marveled, “He’s a football player? Look at how tiny he is.” And to me he looked even younger than 28. He had a hint of a mustache and a frizz of hair on his chin; he wore a white long-sleeved shirt hiding a forearm tattoo that reads GIFTED ONE. He hoisted his then-3-month-old nephew, who lives at the house with Rice’s half-brother and his girlfriend, into the air. His 15-year-old half-sister had wandered in from her room a little nervously. “Crack my back,” Rice said, leaning into her, and she threw her arms around him. “This is normal,” he later said emphatically about the family scene. “Normal.” He’d say the word 13 times that night, in just an hour at the house, like it was a mantra, giving some kind of reassurance.

We took seats on adjacent couches in the living room. Rice faced a credenza holding a flat-screen TV; my view was of a dining room. “I sleep easy knowing my mother’s here,” he said. As we talked, Rice was alternately reflective and combative, resigned to his notoriety and bothered by it. In his mind, he was both guilty and not guilty. He was forthcoming about assaulting his then-fiancée, Janay Palmer, calling the incident “gruesome” and “horrible” — he couldn’t heap enough awful adjectives on it. But he insisted that it wasn’t fair to reduce him to those seconds. “The hardest part for me was people who don’t know me at all were writing about me or talking about me. I understand the seriousness of what I did. But I’m like, Man, they just don’t know who I am.”

For six seasons, Rice had been among the best running backs in football — given his size, it was common to say that, pound for pound, he was the best. He made the Pro Bowl three times, led the Baltimore Ravens to the Super Bowl in the 2012 season, and signed a contract that would pay him at least $35 million over five years. It was a deal of notable length — these days, brutalized running backs are almost interchangeable, with on-field value precipitously dropping after age 27. But by then, Rice was also enormously valuable to the team — and the league — off the field as a sort of golden-boy goodwill ambassador. He had become a local hero in New Rochelle, where he paid for summer basketball leagues for disadvantaged youth and threw barbecues in the Hollow, the crime-ridden projects in which he’d grown up and where his mother had been raised, too. “He gave us hope,” as one New Rochelle friend said to me, reaching for an elegiac tone. And he’d become a charismatic community leader in Baltimore, where he was a philanthropist and what the Ravens called their “go-to guy” for community events. Rice, who’d never been in trouble, embraced the role, telling kids, “If I can do it, you can.” He liked giving back, but community service was also, he later explained to me, partly a way to stay away from home, and Janay.

And then, a little over a year ago, in the early-morning hours just after Valentine’s Day 2014, in an elevator at the Revel hotel in Atlantic City, Rice struck Janay, who collapsed on the floor. Four days later, a video from a security camera outside the elevator leaked, and millions of viewers watched Rice drag Janay’s immobile body out of the elevator. NFL commissioner Roger Goodell suspended Rice for two games — a trivial punishment but consistent with what Goodell later called an outdated league protocol.

But the video from inside the elevator, which leaked seven months after the incident, showed the blow itself. The league already had a domestic-violence problem — at least a dozen players accused of assault played in the NFL last season — and Rice’s two-game suspension had led to calls for Goodell’s firing. When TMZ posted the new video, the Ravens fired Rice, and Goodell suspended him indefinitely from the league the same afternoon.

The public judgment on Rice seemed unanimous: Nobody felt he should have a future in the sport, and NFL insiders believed that the tape meant he would never play in the NFL again. The CEO of the National Congress of Black Women called him the “poster boy” for domestic violence. Columnist Mike Lupica described him as “an unemployed wife beater.” Even President Obama weighed in: “Hitting a woman is not something a real man does,” he said in a statement.

But in late November, Rice fought to overturn his indefinite suspension and won — under the governing labor law, a player can’t be penalized twice for the same act. And now, after sitting out the 2014–15 season, Rice is eligible to play again, and hopeful. He could be picked up at any time, he says, although rosters tend to settle in May, right after the NFL draft, which means his chances for a return this season could become clear in the coming weeks. The main obstacle is what NFL insiders call “the visuals” — any team that picked him up would face nightmarish publicity, as well as pressure from sponsors concerned they’d be seen as endorsing a repugnant act by a repugnant character. But in a league with a history of forgiving repugnant characters (Vick has returned to the field after a prison sentence, for instance), there were also concerns that went beyond reputation, about just how much an aging Rice could actually add to a team on the field.

Like most athletes, Rice has few doubts that he could contribute, and over the past year, he’s made a point of staying fit — working out twice every day, losing close to ten pounds, and boasting that he’s in the best shape of his life. And he’s made it clear how much a return would mean to him — including possibly, in exchange for the chance to redeem himself, playing for the league-minimum salary (for a player with Rice’s experience, about $870,000). Perhaps most important for a comeback, he’s embarked on a sort of image-repair campaign, guided by corporate- and crisis-PR specialist Matthew Hiltzik, which is why, after spending weeks speaking about Rice with people he grew up with in New Rochelle, I was now talking with him.

It’s not the first time Hiltzik’s expertise has been called on by a high-profile star — a former political strategist who has worked for Hillary Clinton, Hiltzik has also advised celebrities in trouble, like Justin Bieber, Alec Baldwin, and Ryan Braun. Hiltzik began by arranging interviews with Janay by ESPN (which allowed her to have editorial control over her own interview) and NBC’s Today, both of which presented an alternative story: Rice was not a monster, but a good guy who made “a mistake.” The singularity of the event was crucial to their narrative. Over the course of hours of conversation with both Ray and Janay, that night in Ray’s mother’s home and over the next few weeks, he and Janay insisted repeatedly that, although victims’ advocates suggest a single incident of abuse is extremely rare, the assault in the elevator was an isolated event — an account I heard echoed in interviews with many of the Rices’ friends. As Janay told police in the aftermath of the incident, “That’s not us.” She married Ray the day after he was indicted.

When Ray and Janay spoke about their relationship, they did their best to present it as a happy one, and getting happier. I’d seen them together at an event over Christmas, and they were joking and comfortable, kidding each other over who would wear an oversize Santa cap. But the picture that emerged in conversation was of a relationship that had always been full of challenges. “Being in a relationship with a celebrity is hard,” Janay said. “Everything is about them. Ray had to have people around him.” Janay would find herself telling him, “We don’t need all these people at the house.” Ray had even given her a nickname; he called her “Dreamkiller.”

Rice met Janay Palmer when she was 14 and he was 15. She lived a town over, in Mount Vernon, and was a different kind of girl from the ones Rice knew in the Hollow. His father had been murdered when he was 1; her father, Joe, was a Teamster who made a decent living. As the oldest child, Ray was assigned the role of the man of the house, taking jobs on top of schoolwork and football; his mother would draw him aside and say, “Ray, I need money.” The Palmers sent Janay to parochial school, where she was president of the student council. When Ray got into football, he’d wake up at 5 a.m. to train, springing up and down the Hollow’s stairs. When Janay was interested in fashion, her parents sent her to classes at F.I.T. And while Ray liked Janay from the moment he talked to her, he was attracted to her family, too. “I did come from a two-parent household, which I know drew him,” Janay told me. “He became one with my family.” Ray took to calling Janay’s father Dad.

Rice was dominant on the football field — “When I didn’t want to think about the situation I was in, I had football,” he said. At the youth level, an opposing coach once refused to let his team play unless Rice was taken out of the game, and in high school, he’d lead New Rochelle to a state championship. But because of his size, he wasn’t heavily recruited by college coaches. A few thought he’d make a good defensive back, but he chose Rutgers for the chance to play in the offensive backfield. “They weren’t going to take the ball out of my hands,” Rice told me. “They were one of the worst teams in the nation, but I said to myself, I see an opportunity. My goal when I went there was for people to say Ray Rice and Rutgers football in one sentence.” They would. In 2006, he led Rutgers to its first bowl-game victory; the next year, he’d break numerous school rushing records.

Rice entered the NFL draft after his junior year and was selected by the Ravens in the second round. He was 21 and hadn’t ever lived far from New Rochelle. “I was scared to be alone,” he recalled. He took a cousin with him to Baltimore, and he wanted Janay to come, too, which surprised her. They’d been friends for years, but only romantic for a year or so; she hadn’t thought they were that serious. But when he cried and asked her to move with him, she was thrilled. “I knew I was the one then,” she said.

“He wanted her to live with him,” recalled Janay’s mother, but her parents vetoed the idea of cohabitation. “You need to concentrate on what you’re about to get into,” Joe Palmer told Ray. “You don’t want a person to sit around living off you. You want her to have her own life so you can be proud of her.” But Janay had been accepted to Towson University outside Baltimore, and her parents said it was all right to go. “Everything fell into place,” Janay said.

In Baltimore, though, Rice’s priorities were elsewhere. “Football came before everything and everyone,” he told me. Janay accepted that as necessary, but it was a sore point. “It was definitely frustrating. It was hard knowing I wasn’t his first priority,” she said.

And it got more challenging when she got pregnant and gave birth, in early 2012, to Rayven, named after Ray and his team. Rayven didn’t sleep well, and “I felt I was doing everything by myself,” Janay said. “After a while, I resented that. I felt like a walking zombie. I told Ray he needed to change more diapers.”

Instead, Rice found excuses to stay away. He overbooked charity events — often three back-to-back on his one day off each week. Afterward, “I get home, I’m spent,” he recalled. “There’s no time to talk. ‘I got practice the next day.’ ” He’d just head off to sleep.

“It got to the point where if she had an issue, I would basically just go silent,” he told me. “There wasn’t a lot of yelling, screaming, nothing. I would just wake up, go to practice. Then game day gets here. I’d rush for three touchdowns. The family’s over at the house. She’s still got that problem she’s thinking about. And I think, I scored three touchdowns today. Everything’s all right.”

“That’s not what a man does,” Janay would tell him. “I know what a man is supposed to be. I know how a man acts in a relationship. I know what a father is. I experienced it.” Later she told me, “I wasn’t trying to be malicious, but it had to sting.”

Valentine’s Day 2014 marked the beginning of an offseason that Rice had been looking forward to for months. The 2013 season had been the worst of his career, and he’d played through a hip injury, rushing for just half the yards of previous seasons. The Ravens didn’t make the playoffs, and part of the blame fell on Rice. Some observers were wondering if his days as a Pro Bowler had come to a close.

Janay had wanted to spend the holiday together. “It’s Valentine’s Day, we should do something ourselves,” she remembered thinking. Instead, “he plans a group thing” in Atlantic City, with his half-brother and his girlfriend and another Baltimore couple. “It was an annoyance to me,” Janay said. “I was a little perturbed, though I didn’t communicate that to him.” She said she was silent during the three-hour car ride.

When they got to Atlantic City, the friends hit the club inside the Revel casino, the Royal Jelly. They ordered a few bottles of vodka. Rice had been on a cleanse, and a few drinks did him in. They left for the Revel’s late-night restaurant, where Rice went to the bathroom and threw up. Back at the table, Rice and Janay bickered, Rice fiddling with his phone. “She put her hands in my face,” he later told an arbitration panel. Rice got up and left, heading back to the room.

“I’m in the clear,” he later said. He stood by the elevator, texting his friend back at the table, “Is everything alright?” Janay, though, had followed him. Seeing him on his phone, she went for it. Rice cursed at her and made a “very vulgar” comment. She walked by, turned, took a step toward him, and slapped his face. “We were drunk and tired,” Janay said later. Rice followed her slowly to the elevator.

Rice and Janay had been instructed not to talk to me about what happened inside the elevator, but confidential transcripts from the arbitration hearings tell the story. Janay slapped him again, and then Rice struck her with his open palm. It was a hard blow. She was furious, balled her fists and lunged at him. Rice hit her on the side of the head with his left hand, and she was knocked backward, banging her head against the rail of the elevator. Ray later said he was stunned by the sound of the impact.

The blow looked awful. But what Rice did next was a different kind of ghastly — dragging his unconscious fiancée from the elevator and depositing her in its doorway, face down. He didn’t comfort her or kneel next to her. Her legs had come apart. He nudged them closed with his foot, then a hand, as if her modesty were the issue. A security guard arrived, bent beside her, and told Rice to move away. Rice paced, looked up at the ceiling. Later he claimed he was terrified and in shock, but he seemed indifferent — callous, as Goodell later said. In the hall, his first call was to his agent, then his mother. “Ma, I made a huge mistake,” he told her. “I’m probably going to go to jail tonight.”

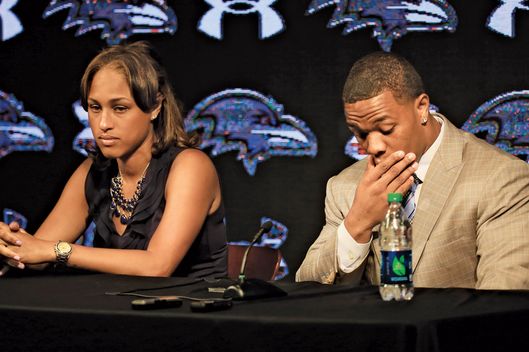

Rice did go to jail, but for just a few hours. A few months later, on May 20, a judge allowed him to enter a diversion program rather than face prosecution on assault charges. Three days later, as if to celebrate, the Ravens organized a carefully scripted press conference, designed to show support for Rice and allow him to acknowledge how poorly he’d behaved, apologize for it, and ask for forgiveness — all while Janay was by his side. The optics were good, but the press conference was a disaster. The Ravens had given Rice talking points, which he scrolled through on his phone as he spoke. He apologized to the NFL and to his fans, but not to his wife, thanking her instead “for loving me where I was weak and building [me] up where I was strong.” Then Janay read a brief statement apologizing for her part in the incident. “I do deeply regret the role that I played.” The Ravens immediately tweeted her apology, triggering an uproar: Rice had apologized to everyone but the person who most deserved an apology. The team had trotted her out to take the heat off him, even blame herself for the beating.

A year after the incident, Rice was still idling at home. Other domestic abusers had a different fate, like Greg Hardy, a star pass rusher convicted of assaulting his girlfriend, who had been signed after he’d appealed and had the conviction overturned — the Cowboys gave him an $11 million deal, and the owner’s daughter called it “an incredible opportunity.” But unfortunately for Rice, “there’s just not that much difference between a good running back and a great one,” one scout told me. Considered “an aging player” at a dispensable position, Rice is likely to find few takers, even at the league-minimum salary. “There won’t be a lot of opportunities,” said Leigh Steinberg, the agent on whom the film Jerry Maguire is said to be based. “But he’s too good not to get a shot. It only takes one team out of 32.”

Rice told me that he’s thinking of this as an injury year. “Except I wasn’t physically hurt, I was mentally hurt.” As part of his agreement with New Jersey prosecutors, Rice has been in counseling, and you can hear the language of therapy as he speaks about the incident and his life since. In his telling, the “mistake” in the elevator was a starting point that had sent him on a journey of self-discovery. His evolving view is that his God-given talent had been, in part, a trap. “I was told since high school that I’d be in the NFL. Once my football playing started taking off, and I started scoring all those touchdowns, I was the golden child.” People cared about football, not about him. “Nobody ever had courage enough to try to give me the tools of life,” he said, and he’d suppressed his unhappy past, which he’d come to believe held the secret to who he is. “I’m learning to love myself,” he said. “It’s unfortunate that it took this situation for me to face myself.”

“There will always be pain,” Janay said. “He’s figuring out ways to cope with it.”

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of Rice’s image-rehabilitation project is that it involves the testimony of his therapist — Dr. Paul Ball, a large, shaven-headed ex–college football player with the booming voice of a Sunday preacher, which he is. It is exceptionally unusual for a therapist to speak publicly about a patient, but Rice asked Ball to help, and Ball, who had been counseling the couple even before the assault, had agreed. “I consider Ray one of my sons,” Ball explained.

“He was in a very dark place,” Ball said, recalling his first meeting with Rice after the assault. “He was very, very remorseful and very, very sorry and in a lot of pain.” Rice talked about “checking out.” “I gave him probably three sessions to cry,” Ball said. “And then, after that, no more crying.”

“Dr. Ball was the first person that made me open up about my past,” Rice said. “It was the first time I felt, Man, I’m not hiding anymore!” They talked about Rice’s childhood, and Rice felt he had a revelation. “I forgot about the pain and agony that I had to go through growing up, the stuff that my mom went through. Stuff that I had to bear as a kid,” he explained. “The thing that kids did growing up — I didn’t have that childhood,” Rice told me. “I had to provide. That was my life from 13 to 28. I’m still providing. It was scary.” Ball told Rice: “That kind of responsibility is way, way, way over the top.”

As we sat together, Rice looked around the room. He was quiet, as if to let the moment sink in. His mother’s Shih Tzu pup lay on the floor staring at him like an adoring fan. Rice leaned forward, eager to continue. “There was a hurt child in there, you know.” He tapped his chest. “I was still hurt from my past.”

Ball had broken Rice down, and then, Rice said, “he built me back up.” Ball is a pastoral counselor, and his therapeutic approach is rooted in the Bible. He assured Rice that everything happens according to God’s plan, wisdom that Rice dutifully accepted. “Dr. Ball made me change my priorities,” Rice said. “You’ve got to understand that growing up, football meant more to me than anything else. And now my priorities are God, family, then football.”

Ball pressed Rice to imagine a life in which football was not his top priority. After all, it’s possible he’ll never play again. “I love kids,” Rice told me. He thought he might work with them, he said, trying to sound cheerful and not quite succeeding.

One day, a few months after the assault, Ray turned to Janay. “Damn, this ain’t how I want my career to end.”

“What’s important?” she asked.

Ray knew the answer. “My family, you, Rayven.”

Rice knew what the domestic-violence victims’ advocates would say. His behavior was classic, almost cliché. After the abuse, the abuser feels terrible; he overcompensates until the next flare-up. Rice didn’t care. He’d always worked harder than anyone else, and now he’d put his all into his new home life. In our conversations, he took every opportunity to praise Janay — so much so that the praise sometimes felt a bit strained. “The biggest accolade in the house, even though I was winning the Super Bowl, on a personal-achievement note, is Janay graduating from Towson University. She was going to be, still is going to be, something special in life.”

Rice also said he was paying attention to the small stuff. He goes with Janay to Target and Walmart — “Ray loves a deal,” his mother-in-law said. The Rices don’t have a nanny, and he helps with child care and rushes around doing chores. “She’s a neat freak. You know how many points doing the dishes gets for me?”

“This year has been good for the family,” Janay said. “Ray spends as much time with us as he possibly can.” Most mornings, Rice takes his daughter to school — “She thought I was a traveling salesman,” he’d been away so much. He cut back on the crowds at the house, but he’s a talker and constantly dialed friends and family. He even said he feels guilty about the position he put the league in. “It’s unfortunate that my actions caused collateral damage that I never could have imagined,” he told me. “Unfortunately, even though I was responsible for creating the situation, commissioner Goodell ended up taking quite a hit for it.”

Ray, Janay, and Rayven make frequent trips back to New Rochelle, where they have relatives, friends, and admirers. And they’ve bought a house in Connecticut, closer to home. Rice vows never to move again. Earlier, when his picture had been removed from the New Rochelle high school’s wall of fame, people at the Hollow staged a spontaneous candlelight vigil. “He made a mistake,” said his friend Henderson Clarke, a former basketball player whose own prospects had been dashed when he had a run-in with the law. “We all make mistakes.” Over Christmas, Rice was even invited to give away $10,000 to an underprivileged-families charity in Westchester County, a risk for the sponsor, Steiner Sports, since charities want no association with a national villain. It was, of course, filmed for local news.

My time with Rice was coming to an end — he had to pick up Janay for dinner. I asked him how it would feel if his career was over. “Honestly, it would hurt, because I didn’t leave the game the way I wanted to. I didn’t leave the game because I wasn’t good enough. I’ve still got a whole lot of game, and I’m not ready to call it quits.” Rice paused a moment. He knew what he had to say. “But I don’t love football more than I love my wife.”

*This article appears in the April 6, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.