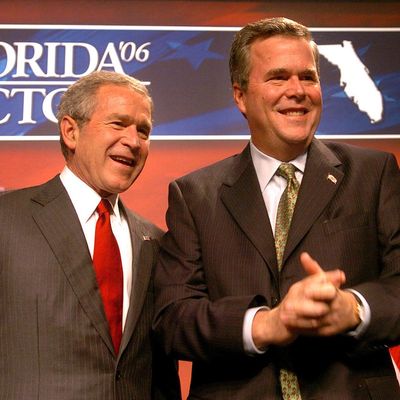

It’s been a rough-and-tumble week for Jeb Bush. The definitely-maybe presidential candidate, who is now ranked fifth among GOP hopefuls by a new national poll from PPP, has also been having the darndest time trying to explain how he would have handled his brother’s signature foreign-policy failure, the Iraq War. That was until yesterday at least, when Jeb finally declared that, no, knowing what he knows now, he would not have invaded Iraq in 2003. And it only took him four tries.

Monday on Fox News, Jeb started the fire by commenting, “I would’ve [authorized the invasion], and so would’ve Hillary Clinton, just to remind everybody. And so would almost everybody that was confronted with the intelligence they got.” When that didn’t go over very well, Bush tried to clarify Tuesday on Sean Hannity’s radio show, insisting he misunderstood the original question and that while “mistakes were made” in the run-up to the war, “I don’t know what that decision would’ve been.” The next day at a town hall meeting in Nevada, Jeb was convinced that answering hypothetical questions would be a disservice to veterans.

By round four on Thursday, it seemed the central disservice was being done to his campaign. Speaking at an Arizona town hall, Bush finally gave up and concluded, “Here’s the deal: If we’re all supposed to answer hypothetical questions — knowing what we know now, what would you have done — I would have not engaged. I would not have gone into Iraq.”

But how will this week’s debate, which has included a lot of piling-on from other Republican candidates, actually affect Bush’s chances at both the GOP nomination and the presidency? FiveThirtyEight’s Harry Enten notes that while Republican voters aren’t typically that concerned about the Iraq War, the general electorate is a different story:

Only 26 percent of all Americans in the NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll said going to Iraq was worth it. Of course, it’s not just about the war in isolation. The big issue is that it’s Bush’s brother’s war. Jeb Bush continues to have a big problem because he’s the brother of the most unpopular president in recent history. An April 2015 Fox News poll found that 58 percent of voters said that being related to a former president was a disadvantage for Bush. By not giving a clear answer on Iraq, Bush will allow others to wrap him in his brother’s unpopular foreign policy legacy — a legacy that helped lead to a Democratic president in 2008.

For a relatively moderate candidate like Bush, his entire primary campaign is built around electability (for example, look at his position on immigration reform). Electability is a good strategy, but Bush’s waffling position on Iraq could undermine it. Donors and the all-important party actors might react negatively to Bush’s apparent inability to stand up to the type of heat he’ll face in the general election.

Meanwhile, Jeb is clearly still uncomfortable with the comparisons and controversies regarding his family. At an RNC event on Thursday night, Bush remarked, “I’m not going to go out of my way to say that my brother did this wrong or my dad did this wrong. It’s just not going to happen. I have a hard time with that. I love my family a lot.” He added, “I know I am going to get beyond being George W’s brother, for which I am extraordinarily proud as well.” Still, conservative commentator Matt K. Lewis insists that, his brother’s keeper or not, if Jeb wants to be president, he’s going to have to pull farther away:

He needs us to show us how he’s different [from his brother], what he’d do differently, and where he and his brother diverge on issues both foreign and domestic. Where does he stand on the bailouts, the massive growth in government spending, the Medicare expansion, and all the other facets of the Bush presidency that still anger conservatives? He has to make a break with all that if he wants to make it to the nomination and, ultimately, the White House.

This insanely difficult choice—whether to stay with his brother or leave him behind—will largely define Jeb’s candidacy. The Bushes have always prized loyalty, but for Jeb, absolute loyalty to his brother—and winning the presidency—might be mutually exclusive. Some presidents would run over their own mother if that’s what it takes to win an election. What is Jeb willing to say about his brother’s policies—if push comes to shove?

But returning the Iraq question — and questioning — Politico’s Jack Shafer connects Jeb to Hillary Clinton and reflects on the ways in which politicians try to excuse past misjudgments:

As the PolitiFact team points out, Hillary Clinton’s views on the Iraq War have swung equally wide. A member of the U.S. Senate, she voted for the 2002 resolution that authorized military action, and then literally played the “if we knew then what we know now” card in a December 2006 appearance on Today. But the switcheroo wasn’t enough to prevent Barack Obama’s supporters battering her straight through 2008 for supporting a disastrous war that he, then an unknown Illinois politician, had been smart enough to oppose. And we know how that race turned out.

The problem of politics—oh, hell, life itself—is that we never get to know then what we know now. Framing an issue as important as the Iraq War in a whimsical context of a do-over, a do-over with the benefit of perfect knowledge, may make a dazzling question. But it also affords candidates a hiding place. They weren’t wrong, their passive argument goes. Their inputs were wrong! And you can’t fault them for having received the wrong inputs, can you?

It takes political bravery to change a flawed position and accept blame. Theoretically, that’s what we want in politicians—accountability and the ability to self-correct. But shouldn’t the fact that both Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush got Iraq wrong argue against making either president—and for giving the job to somebody who saw through the intelligence “failure”? At the very least, I’d love to hear their answer to that one.

Then again, at least Jeb and Hillary aren’t pretending to be Liam Neeson.