On Tuesday, Jeb Bush proposed to eliminate the Obama administration’s regulation of carbon pollution, and, in keeping with his self-styled goal of “growth at all cost,” proposes to make any further climate regulation essentially impossible. In any other democracy in the world, a Jeb Bush would be an isolated loon, operating outside the major parties, perhaps carrying on at conferences with fellow cranks, but having no prospects of seeing his vision carried out in government. But the United States is different. Here in America, ideas like Bush’s fit comfortably within one of the two major political parties. Indeed, the greatest barrier to Bush claiming his party’s nomination is the quite possibly justified sense that he is too sober and moderate to suit the GOP.

Of all the major conservative parties in the democratic world, the Republican Party stands alone in its denial of the legitimacy of climate science. Indeed, the Republican Party stands alone in its conviction that no national or international response to climate change is needed. To the extent that the party is divided on the issue, the gap separates candidates who openly dismiss climate science as a hoax, and those who, shying away from the political risks of blatant ignorance, instead couch their stance in the alleged impossibility of international action.

A new paper by Sondre Båtstrand studies the climate-change positions of electoral manifestos for the conservative parties in nine democracies, and finds the GOP truly stands apart. Opposition to any mitigation of greenhouse-gas emissions, he finds, “is only the case with the U.S. Republican Party, and hence not representative of conservative parties as a party family.” For instance, the Swedish conservative party “stresses the necessity of international cooperation and binding treaties to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions, with the European Union and emissions trading as essentials.”

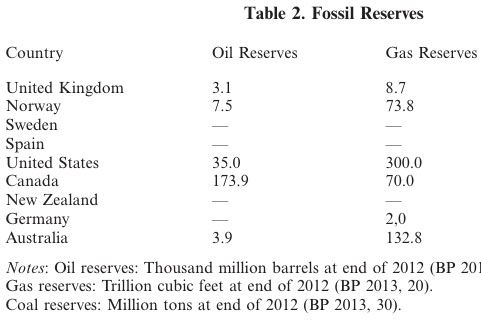

Okay, you might say, that’s just Sweden. But all of the other non-American conservative platforms follow similar themes. Germany’s conservative platform declares, “[C]limate change threatens the very foundations of our existence and the chances of development of the next generations.” Canada’s, writes Båtstrand, “presents both past and future measures on climate change. The past measures are regulations on electricity production, research and development on clean energy (including carbon capture and storage), and international cooperation and agreements including support for adaptation in developing countries.” Even coal-rich Australia has a conservative party that endorses action to limit climate change. All of this is to suggest that the influence of the fossil-fuel industry alone cannot explain the right’s brick-wall opposition to any steps to reduce emissions within the United States. Oil in Canada and coal in Australia both account for a far larger share of their countries’ economies (which are less than a tenth as large as the U.S. economy) than any fossil-fuel reserves in the United States.

Nor can a fealty to free-market theory alone explain the change, either. Free-market ideology traditionally recognizes a role for government when it comes to “externalities,” or actions that impose costs on others. Pollution is the most classic case of an externality — a factory whose production pollutes the air, or a local stream, should have to pay the cost. Even F.A. Hayek, in the anti-statist polemic The Road to Serfdom, conceded, “Nor can certain harmful effects of deforestation, or of some methods of farming, or of the smoke and noise of factories, be confined to the owner of the property in question or to those who are willing to submit to the damage for an agreed compensation. In such instances we must find some substitute for the regulation by the price mechanism.” Now, Hayek offered this concession to the role of government in the course of advocating for a pricing mechanism for externalities, rather than a crude ban. But he was recognizing that even the purest libertarians must concede the need for collective action of some kind when it comes to things like pollution.

It is also worth noting that the Republican Party used to fit in with the pattern of other international conservative parties. The Nixon administration created the Environmental Protection Agency and passed the Clean Air Act. The first Bush administration passed amendments strengthening it. Both of those presidents are considered, correctly, to be aliens to the conservative movement. The conservative movement has always opposed environmental regulation, and Republican leaders since the first President Bush — the GOP Congress since the era of Newt Gingrich, George W. Bush, and the current Republican presidential field — have followed conservative thinking. Indeed, administrators of the EPA from previous Republican administrations have endorsed Obama’s climate program, but they lack any influence or even legitimacy within the party today.

Rabid opposition is not the only quality that sets the GOP apart from other major conservative parties. The fervent commitment to supply-side economics is also an almost uniquely American idea. The GOP is the only major democratic party in the world that opposes the principle of universal health insurance. The virulence of anti-government ideology in the United States has no parallel anywhere in the world.

And so the “moderate” Republican climate position is that action is pointless, since countries like China will never reduce their own emissions. (No evidence of Chinese behavior seems capable of altering this conviction, which serves the handy function of justifying the desired conservative outcome without leaning too heavily on anti-science kookery.) The more right-wing position within the party — endorsed by the party’s leading presidential candidate and the chairmen of the science committees in both houses — is that thousands of climate scientists worldwide have secretly coordinated a massive hoax. And then the even more conservative position, advocated by the second-leading candidate in the polls, holds not only that climate science is a massive hoax, but so are evolution and the big bang. The “moderate” candidates are still, by international standards, rabid extremists. It is the nature of long-standing arrangements to dull our sense of the peculiar, to make the bizarre seem ordinary. From a global standpoint, the entire Republican Party has lost its collective mind.