The Democratic Party spent 1999 in a state of almost unbroken panic. Even while an incumbent Democrat had presided over an economic boom that delivered the greatest prosperity Americans had enjoyed in decades, they could not escape a sour cynicism pervading the electorate. Al Gore, President Clinton’s chosen successor, trailed Republicans badly throughout the year and faced a stubborn threat from within his own party. The struggles faced this year by the Hillary Clinton campaign reflect those of the Gore campaign 16 years ago — perhaps not in every facet, but the broad contours. A closer look at that campaign, especially its hapless, early stages, reveals a lot about the trouble Clinton faces now, and her prospects to escape it.

After an exuberant election swept a young new Democratic president into power in 1992 after a long period of Republican rule, and a somewhat joyless reelection trudge four years later, by the seventh year of the Clinton administration ennui had set in among the base. Despite high approval ratings, pollsters identified pervasive “Clinton fatigue.” A 1999 Pew poll, for instance, found “three-quarters of Americans say they are tired of the problems of the current administration,” and that these views mapped closely onto voters’ opinions toward Gore. Even though Gore shared Clinton’s popular profile on issues, and did not share his personal failings, he inherited the burden of the latter more than the benefit of the former.

The mechanism that transferred Clinton’s well-known moral failings onto his vice-president was an exceedingly technical fund-raising scandal. Gore made fund-raising calls for the Democratic Party from the White House, which did not violate either the letter or the spirit of the law (the Pendleton Act, which was intended to prevent shaking down potential officeholders for donations). But reporters found Gore’s performance untrustworthy anyway. The vice-president, reported the New York Times in 1997, “used legalistic language, which he repeated verbatim several times, to say he had not violated another law that prohibits anybody from raising campaign money in the White House.” As a result, scandal-tinged themes came to dominate news coverage of Gore. His attempts to create new narratives merely resulted in chortling reporters mocking him for trying too hard to reshape his image, reinforcing their theme that he lacked “authenticity.”

The email scandal currently dogging the Hillary Clinton campaign has played a similar role. The charges are more serious than the accusations against Gore — Clinton’s use of a private email server undeniably amounted to a violation of protocol and poor judgment. It has served as grist for the news media to fixate on a process story upon which it can build larger narratives about her character. Those narratives feed into long-standing ethical concerns dating from the Clinton administration and the Clinton post-presidency, during which the former president profited immensely from relationships with figures who had a clear interest in currying favor, then or in the future, with his wife. The Obama administration has managed to avoid any significant scandals with credibility in the mainstream media (only partisan Republicans still cling to the belief that Benghazi or alleged IRS targeting of opponents were real). Ironically, both Al Gore in 2000 and Hillary Clinton today inherited much of their reputation for shadiness from the same person: Bill Clinton.

The miasma of perceived sleaze hurt both campaigns most deeply with the same constituency: white upscale voters. Economically vulnerable Democrats have historically based their loyalty on the party’s cultural identification and concrete programmatic support. But for more than a century, dating back to the Progressive movement and its attacks on boss rule, upscale white liberals have always recoiled against the perception of sleaze or even mere transactionalism. Gore faced a stiff challenge from Bill Bradley, a Yankee jock-hero with a reputation for probity who promised a newer, cleaner, more inspirational kind of politics. While his candidacy has since receded from memory, it attracted huge crowds and seemed to form the center of a passionate movement. Bradley promised a presidency that would do “big things,” a refreshing appeal after years of stalemate between Clinton and a Republican Congress. More significantly, he promised to bring a kind of purity to the campaign itself. “I am trying to run a different kind of presidential campaign,” he declared in his announcement speech. “I’m calling us to renew our faith in each other.”

That same voting bloc was attracted to Obama’s idealistic campaign in 2008 and has listened attentively to Bernie Sanders. While his frankly socialist policies have energized the party’s economic left, Sanders has soared just as much upon his stylistic contrast as an authentic, independent politician who can’t be bought and operates outside of the machine. His unkempt hair and wonky, discursive speaking style has identified him as an indie brand, a far broader base of appeal than just the “socialist candidate.”

Bradley’s candidacy had become the vessel for any Democrat who had grown disenchanted with the Clinton administration. Bradley won endorsements from Robert Reich, the outspoken populist former secretary of Labor who had turned critical of his former boss for focusing too heavily on deficit reduction, and from Bob Kerrey, the former Nebraska senator who denounced Clinton for focusing too little on deficit reduction. In this polarized age, the pockets of discontent against Obama are smaller than those faced by Clinton 16 years before, but hints of the same dynamic can be found. In West Virginia, whose Democrats have turned against Obama en masse, Dave Weigel found pockets of support for Sanders, whose environmental stance is no friendlier to coal than Obama’s or Clinton’s.

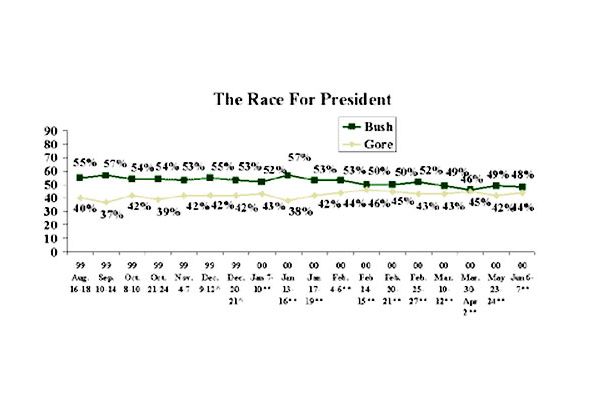

By this point in 1999, Gore’s campaign had taken on water. Bradley had caught him in New Hampshire and had started to run far ahead of the tarnished vice-president in trial heats against the Republicans. In fact, Gore at this point looked like a goner. Polls showed George W. Bush, the runaway Republican leader, crushing him by landslide margins head to head:

The generalized desire for something different has likewise dragged down Clinton’s standing. A recent poll found that 57 percent of respondents preferred “the candidate [who] would change most of the policies of the Obama administration,” as opposed to just 41 percent who prefer to continue them. Many surveys now find her losing matchups against leading Republicans.

The Clinton campaign can draw some encouragement from the parallel. Al Gore did not lose by double digits. He won the popular vote by half a percentage point. Hillary Clinton, who is not trailing her opponents anywhere near as badly as Gore trailed Bush, will probably recover, too, as the election draws closer and ingrained partisan allegiances reassert themselves. On the other hand, the precedent also shows the challenge she will face. A bored and disillusioned base, the likelihood of indefinite gridlock, and a skeptical media is a formula not necessarily for defeat, but surely a long, hard, joyless slog.