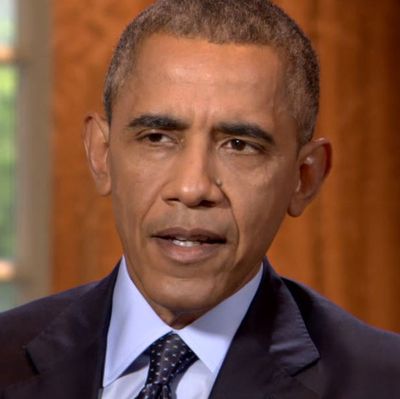

Last week, the upsurge of political correctness made the leap from an intramural squabble within the left into the broader political debate. While the attacks in Paris overshadowed them, President Obama — who has commented on the issue before — spoke at greater length in an interview with George Stephanopoulos. Obama really zeroes in on the central issue, which makes his answer worth reading in its entirety:

OBAMA: […] The civil-rights movement happened because there was civil disobedience, because people were willing to get to go to jail, because there were events like Bloody Sunday. But it was also because the leadership of the movement consistently stayed open to the possibility of reconciliation and sought to understand the views, even views that were appalling to them of the other side.

STEPHANOPOULOS: Because there does seem to be a strain on some of these campuses of a kind of militant political correctness where you shut down the other side.

OBAMA: And I disagree with that. And, it’s interesting. You know, I’ve now got, you know, daughters who — one is about to go to college — the other one’s — you know, going to be on her way in a few years. And then we talk about this at the dinner table.

And I say to them, “Listen, if you hear somebody using a racial epithet, if you hear somebody who’s anti-Semitic, if you see an injustice, I want you to speak out. And I want you to be firm and clear and I want you to protect people who may not have voices themselves. I want you to be somebody who’s strong and sees themselves as somebody who’s looking out for the vulnerable.”

But I tell ‘em — “I want you also to be able to listen. I don’t want you to think that a display of your strength is simply shutting other people up. And that part of your ability to bring about change is going to be by engagement and understanding the viewpoints and the arguments of the other side.” And so when I hear, for example, you know, folks on college campuses saying, “We’re not going to allow somebody to speak on our campus because we disagree with their ideas or we feel threatened by their ideas —” you know, I think that’s a recipe for dogmatism. And I think you’re not going to be as effective. And so, but I want to be clear here ‘cause, and it’s a tough issue because, you know, there are two values that I care about.

I care about civil rights and I care about kids not being discriminated against or having swastikas painted on their doors or nooses hung — thinking it’s a joke. I think it’s entirely appropriate for — any institution, including universities, to say, “Don’t walk around in blackface. It offends people. Don’t wear a headdress and beat your chest if Native American students have said, you know, ‘This hurts us. This bothers us.” There’s nothing wrong with that.

But we also have these values of free speech. And it’s not free speech in the abstract. The purpose of that kind of free speech is to make sure that we are forced to use argument and reason and words in making our democracy work. And you know, then you don’t have to be fearful of somebody spouting bad ideas. Just out-argue ‘em, beat ’em.

Make the case as to why they’re wrong. Win over adherents. That’s how — that’s how things work in — in a democracy. And I do worry if young people start getting trained to think that if somebody says something I don’t like, if somebody says something that hurts my feelings that my only recourse is to shut them up, avoid them, push them away, call on a higher power to protect me from that. You know, and yes, does that put more of a burden on minority students or gay students or Jewish students or others in a majority that may be blind to history and blind to their hurt? It may put a slightly higher burden on them.

But you’re not going to make the kinds of deep changes in society — that those students want, without taking it on, in a full and clear and courageous way. And you know, I tell you I trust Malia in an argument. If a knucklehead on a college campus starts talking about her, I guarantee you she will give as good as she gets.

Since I wrote about this in January, the reaction has changed noticeably. The tone of liberal disagreement has moved from angry denial to exasperated annoyance with having to discuss the issue. Danielle Allen, capturing a widespread sentiment at the moment, perfunctorily endorses the importance of free expression, but urges, “On this subject, I would say, there’s little to see here. Move along.”

But — and this is the reason I have been banging on about the subject so remorselessly — the emergence of p.c. is not just a handful of college kids acting silly. It raises ideological questions that strike at the heart of liberal values.

It’s worth stepping back and considering why it is that political correctness suddenly seized hold of national attention so quickly. The events at neither Yale nor Missouri are especially outrageous in comparison with things that have happened elsewhere (punishing newspapers for publishing op-eds, shouting down or canceling speeches, closing down plays, vandalizing and threatening authors of mild satire, among other offenses). What may set them apart is the availability of video, which provides visceral access to the style of p.c. discourse that people outside its culture previously had trouble imagining.

A recent column I wrote on this drew a comparison with its ideology and Marxism, leading a number of left-wing critics to conclude that I had called p.c. culture Marxist. I did not, but the question of just how to define p.c. ideology is an important one. The column drew a comparison, not an equation, between p.c. and Marxism. Obviously, p.c. ideology is not Marxist — it has no dialectic theory of history, and no real program or end point, among other differences. The case I made in my longer story in January is that the p.c. left “has borrowed the Marxist critique of liberalism and substituted race and gender identities for economic ones.” P.c. thought substitutes a model of group rights for the liberal model of individual rights. It dismisses liberal arguments for universal rights as a defense of privilege. And since it places the conflict between privileged and oppressed classes at the center of its thinking, it treats political rights as a zero-sum conflict — any defense of political expression from members of privileged classes threatens the rights of the oppressed. Some of these arguments against liberalism have been made in serious ways by theorists of the left, like the radical scholar Catharine MacKinnon (who is also not a Marxist).

All this is to say that political correctness and Marxism do not look at all alike from the inside. From the liberal perspective, however, they share an important resemblance. They both reject liberal political theory in fundamental ways. Many adherents of p.c. openly reject free speech. “I personally am tired of hearing that First Amendment rights protect students when they are creating a hostile and unsafe learning environment for myself and for other students here,” announced the vice-president of the Missouri Students Association. The official demands of protesters at Amherst include that the university president “must issue a statement to the Amherst College community at large that states we do not tolerate the actions of student(s) who posted the ‘All Lives Matter’ and ‘Free Speech’ posters.” (Yes, the protesters are officially demanding that the administration declare it will not tolerate pro-free-speech sentiment.)

If you believe in liberalism, the p.c. left’s rejection of liberal ideals is its defining feature. From the liberal standpoint, the liberal respect for individual political rights provides an essential guardrail against abuse. A liberal would predict that illiberal ideologies will inevitably abuse whatever power they obtain. And that prediction has been borne out repeatedly.

Obviously, within the rule of American law, the p.c. left has limited power. It can shut down or intimidate critics on some campuses in troubling ways, but since it is operating on American soil, it can’t threaten the fabric of the Constitution. That the p.c. left may be imposing hegemony on tiny corners of American life — quads, campus newspapers, free-speech zones, dorms — speaks to the geographic limits of its reach but does not absolve its character. Its illiberal actions spring inevitably from its illiberal theories.

The more damaging impact of political correctness is its imprint on progressive politics. Liberals correctly believe that prejudice is embedded deeply in our social structures and our consciousness, and have to be accounted for in explicit ways. It is necessary to empathize with the perspective of others, and it is more necessary for people accustomed to social privilege to do so, since those who do not face the discomfort of racism and sexism have difficulty imagining its effects.

But p.c. demands far more than this. Even while placing issues of identity at the center of nearly all politics, it deems these questions beyond legitimate disagreement. As Roxane Gay put it in a recent debate with me, “when we’re talking about gender and race, these are not things that are debatable.”

One can see p.c.’s impact well beyond its most obvious campus redoubts. The spread of p.c. has led progressives into blind alleys. The left may be correct about the general existence of widespread problems like sexual assault on campus and racist policing, but clung to false accounts of a horrific rape at the University of Virginia and the cold-blooded murder of a surrendering Michael Brown. Many of us mocked anybody who raised what turned out to be legitimate questions about those incidents as “rape deniers” or racists. The spread of that misinformation discredited the causes liberals care about. In these instances and others, an almost mechanical process of outrage-generation has crowded out thought.

Political correctness is, as Obama puts it, “a recipe for dogmatism.” Liberals have to face up to the question of whether we want to accept an epistemology that shuts down virtually all debate on the sweeping range of political questions related to identity. The important threat it poses is not so much toward the dissidents it shouts down within the progressive enclaves it manages to dominate, but to the character of liberalism itself.