The 20th century was a really strange period in American politics. You had Southern right-wing white supremacists sharing the same party as civil-rights activists; you had one election cycle where both parties were fervently lobbying the same candidate (Dwight Eisenhower) to run as their party’s nominee. The comfortable ideological overlap between the two parties made it normal for many voters to swing back and forth between them for idiosyncratic reasons. The parties themselves barely held together: George Wallace led a bloc of conservative, white working-class defectors out of the Democratic Party in 1968; John Anderson did the same with liberal Republicans in 1980. Both those third-party movements prefigured permanent shifts that have since hardened into place, leaving two ideologically coherent parties fighting bitter trench warfare over a tiny, and steadily shrinking, no-man’s-land.

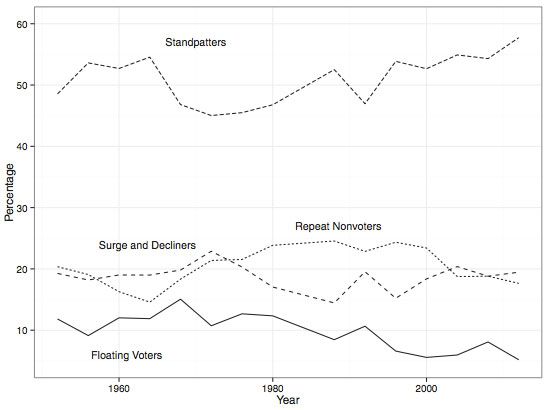

Political professionals in both parties, from Matthew Dowd to Dan Pfeiffer, have noticed the withering of the swing vote. A new paper by political scientist Corwin Smidt (via John Sides) documents the decline of swing voters, or (as many political scientists call them) “floating voters,” which means voters who pull the lever for a different party than the one they supported in the previous election. From the 1950s through the 1980s, 10 to 15 percent of voters floated between the two parties in presidential elections. Recently that rate has fallen to about 5 percent:

The sorting of American politics into semipermanent, warring camps unfolded over decades. But the red-blue map that first came into public consciousness during the 2000 election created a searing impression of a cultural divide between a Democratic Party rooted in the coasts and upper Midwest and a Republican Party dominating the old Confederacy, Appalachia, and the Mountain West. Smidt points out that the jarring events of George W. Bush’s first term — a recession, a terrorist attack, a war in Iraq — failed to dislodge the hardening partisan loyalties. “After having gone through a recession and a war,” he writes, “pure independents were more stable in their party support across 2000–04 than strong partisans were across 1972–76 and about as stable as strong partisans across 1956–60.” The partisan voter of a generation ago switched parties more frequently than today’s independent voter.

The polarized stalemate leaves both parties dissatisfied. Republicans — because they are spread more efficiently, have gerrymandered state and national legislative districts, and vote more frequently in non-presidential elections — have a hammerlock on the House of Representatives and dominate state government. Democrats continue to advance their policy goals through executive action emanating from the White House. Democrats and Republicans alike have both strategized to break through the stalemate by strategically targeting constituencies across the trenches.

But every effort to break the stalemate in the age of polarization has failed. Red-state Democrats and blue-state Republicans have tried to create separate, localized identities for their candidates that can allow them to compete in hostile terrain. It doesn’t work because elections at every level have increasingly grown nationalized. The divide between red and blue America is comprehensive. In Kentucky, Democrats tried to woo the electorate by emphasizing practical benefits from the state’s successful health-care exchange, but found themselves swamped by Kim Davis, the war on coal, and Republican messaging that reminded people that Kentucky’s health-care exchange is, in fact, part of Obamacare. Many Republicans have cheerfully boasted of their chances to win over Latino and Asian-American voters by appealing to either their economic or social conservatism, but the reality is that both of those constituencies have progressive views on just about everything. (Tom Edsall drills down into the political leanings of Asian-Americans and points out that they support higher taxes on the rich, a proclivity that rules out the one supposed point of attraction to the GOP.) You can’t pick off opposing voters on social or economic issues when those issues are all wrapped together into totalistic worldviews.

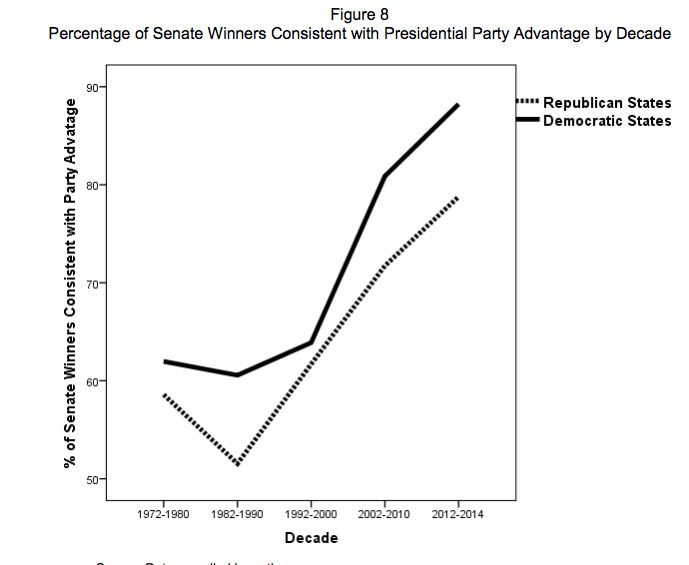

That is why voters used to make individual-based judgments of their candidates for Congress. Now they just vote for the same party all the time:

(Note that Democrats do a better job of electing senators in red states than Republicans do of electing senators in blue states, though both parties are doing it much less frequently than they used to.)

From the Republican point of view, the current stalemate offers reasons for hope. The presidency is the sole locus of the Democratic advantage. Republicans can screw up some races with bad candidates and lose a seat or two; if Democrats screw up a presidential election, then they hand total control of the government to the GOP. What’s more, since voters tend to punish legislators on the basis of which party controls the presidency, Democrats have little chance to generate a backlash against Republican legislative control. The Republicans therefore have a better chance to break the stalemate and win total control of Washington before the Democrats do.

On the other hand, the longer-term trends do bode well for Democrats. If Republicans gain total control of the government in this presidential election, or the next one, they will probably sow the seeds of a backlash that awakens the mostly latent Democratic majority. Almost everybody concedes that rising polarization has changed the rules so as to give the Republican Party an unbreakable grip on Congress for the immediate future. Many people continue to deny that it has changed the rules of presidential politics to give the Democratic Party an advantage. Nate Silver and friends engage in a lot of snarking about the Democrats’ growing demographic advantage in presidential elections but don’t really engage with the evidence. White working-class voters are declining as a share of the presidential electorate by about 3 percentage points every four years — a large scale of change in a closely fought electorate. Republicans can certainly win presidential elections if conditions allow them to dominate among swing voters. But the diminishing number of swing voters makes these swings smaller. Some voters will still move back and forth based on the state of the economy during an election year, or the quality of the candidates, or scandals, and so on. The swings will be smaller with so many voters locked in. Models built on data from the 20th century can’t accurately project how voters will behave in a polarized age. Silver’s 2011 prediction that Obama was a slight underdog relied on the weak economy turning swing voters against the incumbent. He missed the fact that there just weren’t enough of them, because nearly everybody voted for the same party as they had four years before.

Eventually something will happen to break up the current arrangement. Maybe Republicans will one day move to the center, or left-wing activists will push Democrats out of it. (Right now the latter seems more likely than the former.) For the time being, the dominant fact of American politics is that nobody is changing their mind about anything.