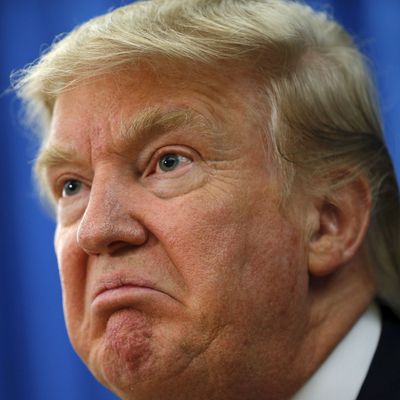

“I like leverage,” Donald Trump has said on many occasions. And there is no reason — on this point, anyway — to question his sincerity. Trump has the power to run an independent presidential candidacy, which is the power to destroy the Republicans’ chances of winning, and he has lorded it over them ruthlessly. Trump signed a “loyalty oath” not to run an independent candidacy, but he appended to his pledge an exception if the party mistreated him — a loophole so enormous it could mean anything Trump wants. In return for his meaningless pledge, Trump has forced other candidates to promise to endorse him if elected — which means the Republican nominee will be either Trump or a candidate tied to his radioactive personality.

Fear of Trump’s independent threat has paralyzed his antagonists. Robert Costa and Tom Hamburger reported Thursday that GOP pooh-bahs met to plan for the prospect of a contested convention, at which, presumably, the non-Trump delegates would have to band together. Such a scenario would still require elaborate displays of respect for Trump, including a prime-time address, for fear of alienating his supporters whose votes will be needed — or, worse still, triggering the I-bomb. Even the GOP’s anti-Trump contingency planning has been hampered by a fear of giving Trump a pretext to go independent. “Because of the sensitivity of the topic — and wary of saying something that, if leaked, would provoke Trump to bolt the party and mount an independent bid — Priebus and McConnell were mostly quiet during the back and forth,” they report.

But the leverage only belongs to Trump if Republicans decide to let the possibility of an independent Trump candidacy terrorize them. If, instead, they decide to accept or even welcome such an outcome, then Trump’s leverage over the Republicans would disappear. And such an outcome might be exactly in the party’s best interest.

1. It is true that an independent Trump run would split the vote and make it almost impossible to defeat Hillary Clinton. But the Republicans don’t stand much of a chance of beating Clinton anyway. This is a premise rejected by nearly all Republicans, and a great many non-Republicans, but the evidence supports it. The electorate has hardened into partisan blocs with very few swing voters, and in a presidential election, the Democrats have a bloc that is somewhat larger. Demographic changes, which reduce the share of white working-class voters by about 3 percentage points in every successive presidential election, are swelling the Democratic edge steadily.

None of this is to say that Republicans cannot win, only that they probably need favorable circumstances to do so. No such circumstances can be seen. The economy is growing steadily, and will stand closer to full employment now than it did in 2012, when Republicans hoped a weak recovery would turn voters against the incumbent Democrats. The rise of terrorism as a first-order public concern might help them, but at the moment, Hillary Clinton — a former secretary of State with easy command of foreign affairs — fares better in polls on handling terrorism than any Republican. One might also imagine that two straight terms of Democratic control might potentially sap its voters of the desire to turn out to vote, but Trump himself is stirring up the primal culture-war passions that will give every constituent part of the Obama coalition — young people, racial minorities, college-educated whites — enough negative incentive to turn out.

2. A Trump independent candidacy would have down-ballot benefits for the party. Trump would split apart the Republican vote at the presidential level, but the socially conservative white working-class voters who turn out to vote for him would overwhelmingly pull the lever for Republicans in Congress (and in state elections). The deepest risk Republicans face is the prospect of an electoral wipeout that puts its control of Congress at risk. An independent Trump candidacy would close off such a prospect.

What’s more, Republicans simply have little to fear from a Clinton presidency. Republican control of the House ensures that Clinton will pass no important liberal legislation, and probably no important legislation at all. If Republicans keep control of the Senate — again, more likely with Trump outside the party than inside it — they will block her from appointing many federal judges.

3. A Trump defection would give Republicans an opportunity to escape the ideological and demographic tar pit into which they have sunk. The GOP has found itself dominated by white identity politics, a kind of geriatric trap. Even the most sophisticated version of its policy agenda, the Ryan budget, ultimately reduces to a scheme of maintaining social benefits for the elderly and middle class while attacking them for the putatively undeserving young. A handful of moderate intellectuals has sought to move the party back toward the center, but their record so far is one of unbroken failure.

A Trump defection might catalyze the formation of a different kind of party. One admittedly imperfect historical analogy comes to mind. In 1948, the New Deal coalition that had carried Franklin Roosevelt to four straight presidential elections began to crack up around Harry Truman. On Truman’s left, former vice-president Henry Wallace ran against Truman as the candidate of the Progressive Party, a quasi-socialistic, and covertly pro-Soviet faction, largely in protest against Truman’s policy of containing the Soviet Union. On the right, Strom Thurmond ran as a States’ Rights Democratic Party candidate to protest Truman’s support for civil rights. Wallace and Thurmond combined to win nearly 5 percent of the national vote, siphoning off what had been the left and right wings of Roosevelt’s majority.

Truman did, surprisingly, win regardless. Ultimately both defections helped shape the postwar course of the Democratic Party for the better. Driving Wallace into opposition snuffed out Communist influence within the Democratic Party. Thurmond’s departure had a more profound, long-lasting influence that played out over decades. Ultimately, Truman’s pro-civil-rights agenda drove away the white South while allowing his party to take the GOP’s northern liberal and moderate base. The Democratic Party crafted by Truman would reject authoritarian ideologies in both their southern white apartheid and their Communist forms.

The contemporary Republican Party has undergone a long, evolutionary ideological transformation over four decades into an intellectually hidebound party whose major splits are no longer based on policy but on affect, willingness to work within existing boundaries of political power, and xenophobia. (It is not a coincidence that the strongest outposts of pro-Trump sentiment within the GOP are organs of white racial paranoia like Matt Drudge, Breitbart, and Rush Limbaugh.) The insurgent radicals have an advantage over the pragmatists in that they are willing to lose elections for the sake of winning the long-term struggle to redefine their party’s identity. The pragmatists are always playing to win the next election, which is why they have consistently lost the long game. Perhaps Trump’s departure would give them their own version of a purifying fire.