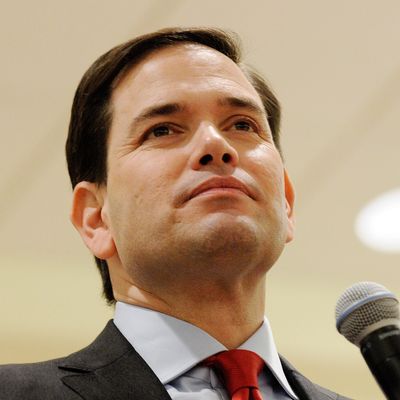

In the final days of his presidential campaign, Marco Rubio took on a noble, elegiac tone, presenting himself as the opposite of Donald Trump. In his valedictory speech, he presented his defeat as a choice — the former Republican savior was simply too good for this world. Deriding Donald Trump’s nasty tone — not by name, of course, being pledged to support the eventual nominee — Rubio declared that he had decided not to take Trump’s easy path for moral reasons. “I chose a different route and I’m proud of that … ” he said. “That would have been the easiest way to win.” This is all revisionist nonsense.

Until the very end, Rubio’s response to the rise of Donald Trump was to co-opt him, not to confront him. When Trump proposed ramping up surveillance of mosques, Rubio lurched to his right. “It’s not about closing down mosques. It’s about closing down any place — whether it’s a café, a diner, an internet site — any place where radicals are being inspired,” he said. “So whatever facility is being used — it’s not just a mosque — any facility that’s being used to radicalize and inspire attacks against the United States, should be a place that we look at.” He indulged dark right-wing fantasies, insisting repeatedly, “Barack Obama has deliberately weakened America” — a right-wing fever dream that made normal compromise impossible. Rubio, breaking from most Republicans, attacked Obama for visiting a mosque.

Rubio could only go so far because only Trump has found a way to break all the norms of American politics at no political cost to himself. Rubio ran a different strategy not for moral reasons but because he thought it would work. His plan was to fashion himself as the frontman for the Republican donor class. Rubio’s proposition to party insiders was that he could spare them from any serious reconsideration of party dogma — except, perhaps, on immigration reform, the one issue where Republican moneymen were happy to move to the center anyway. In place of substantive moderation, Rubio would use his modest upbringing and winning personality (and Rubio truly is likable) to sell old Republican wine in a new bottle. Rubio’s insider strategy conveyed many benefits on his campaign. He raised plenty of money, and overwhelmingly outspent Trump in Florida and elsewhere. Republican insiders showered him with understanding, supplying friendly spin to the media that allowed Rubio to portray a long series of defeats as proto-victories.

It was not only calculation, though, that shaped Rubio’s candidacy. His life has been defined by a fascination with wealth, bordering on worship. Rubio once told a roomful of rich businessmen that the inspiration for his politics came from driving around as a young boy and gawking at the homes of the rich. As a young politician he read Atlas Shrugged, Ayn Rand’s paean to the superiority of the rich, twice. He attached himself to wealthy patrons and moved between politics and lobbying throughout his career, seamlessly blending public service with moneymaking.

His willingness to eloquently champion the interests of the donor class enabled Rubio’s rapid ascent and defined his governing philosophy. In Florida, he proposed cutting property taxes, which fall on landowners, and replacing the revenue with higher sales taxes, which fall most heavily on the poor. His domestic agenda was defined by a tax cut twice the size of the one George W. Bush enacted. Like Bush, Rubio’s tax cut tacked on some small-change tax credits for low-income families, but the bulk of the money went to the top, with 40 percent of the cost of his plan accruing to the richest one percent. He wanted to deregulate the financial industry and eliminate Obamacare — which he repeatedly voted to eliminate without the necessity of a replacement. He refused to accept the legitimacy of climate science, even as his home city is literally disappearing slowly beneath his feet. One of the very few areas where Rubio claimed to stake out untraditional ground was in higher education — but even here, his policy turned out to be deregulating for-profit colleges, one of the shadiest of which had generously funded him.

Rubio’s foreign policy was pure retrograde neoconservatism. On social issues, he defended a complete ban on abortion without exception, even in cases of rape and incest. His propensity to panic under pressure would have made him all the more dangerous in office.

Rubio’s conservative admirers bitterly observed that liberals mocked him because they deemed him a potent nominee. This was not wrong. Despite his inability to out-Trump Trump, who has captured his party’s id, Rubio has maintained high levels of favorability with moderate voters, especially Latinos. His substantive extremism would have proven a liability in a general-election campaign, but it was entirely plausible to believe that Rubio could have smuggled his right-wing policies past the electorate by running on cheerful slogans and a winning smile. The potential to do so is why Rubio may well find himself atop his party’s ticket in a future election. In the meantime, his failure is a bullet dodged.