Can We Please Retire the Notion That Donald Trump Is Hijacking the Republican Party?

There was no Establishment after all.

In mid-July of 2015, a month after Donald Trump announced his presidential run, I joined a gaggle of political junkies in a clubby bar four blocks from the White House to hear a legendary campaign strategist expound on the race ahead. Our guest’s long résumé included service to Mitt Romney and two generations of Bushes. Not speaking for attribution, and not having signed on to any 2016 campaign, he could talk freely. The nomination was Jeb Bush’s to lose, he said. Scott Walker, the union-busting Wisconsin governor then considered something of a favorite, had no chance because he was just “too stupid.” And Trump? Please! Trump represented every ugly element that was dragging down the GOP in presidential elections. But our guy wasn’t fazed. The good thing about Trump, he said, is that he would finally “gather together all the people we want to lose” and march them off the Republican reservation — though to what location remained undisclosed.

That same week, I was at a similar gathering with John McCain, then in a mild fury that Trump had just appeared with the nativist Arizona sheriff Joe Arpaio at a weekend rally in Phoenix. McCain worried that by activating “the crazies” — the same crazies, it politely went unmentioned, that he helped legitimize by putting Sarah Palin on his ticket in 2008 — Trump could jeopardize both the GOP in general and McCain’s own incumbency if challenged in a primary. The senator soon said the same in public, and not long after that, Trump retaliated by mocking his wartime bravery with the memorable insult “I like people who weren’t captured.”

And that, you may recall, was the end of Trump.

His “surge in the polls has followed the classic pattern of a media-driven surge,” wrote the analyst Nate Cohn in the “Upshot” column of the Times, speaking for nearly every prognosticator. “Now it will follow the classic pattern of a party-backed collapse.” Since “Republican campaigns and elites had quickly moved to condemn” Trump’s slam of McCain, his candidacy had “probably” reached the moment when it would tilt “from boom to bust.” How could it be otherwise? As Cohn reiterated a few weeks later, “the eventual nominee will need wide support from party elites.”

The Republican Elites. The Establishment. The Party Elders. The Donor Class. The Mainstream. The Moderates. Whatever you choose to call them, they, at least, could be counted on to toss the party-crashing bully out.

To say it didn’t turn out that way would be one of the great understatements of American political history. Even now, many Republican elites, hedging their bets and putting any principles in escrow, have yet to meaningfully condemn Trump. McCain says he would support him if he gets his party’s nomination. The Establishment campaign guru who figured the Trump problem would solve itself moved on to anti-Trump advocacy and is now seeking to unify the party behind Trump, waving the same white flag of surrender as Chris Christie. Every major party leader — Paul Ryan, Mitch McConnell, Reince Priebus, Kevin McCarthy — has followed McCain’s example and vowed to line up behind whoever leads the ticket, Trump included. Even after the recurrent violence at Trump rallies boiled over into chaos in Chicago, none of his surviving presidential rivals would disown their own pledges to support him in November. Trump is not Hitler, but those who think he is, from Glenn Beck to Louis C.K., should note that his Vichy regime is already in place in Washington, D.C.

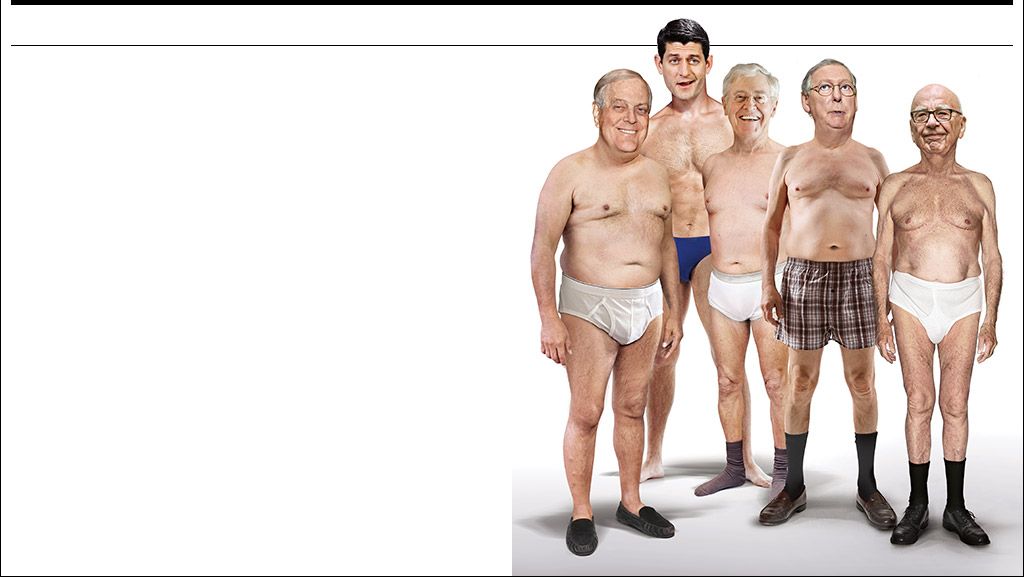

Since last summer, Trump, sometimes in unwitting tandem with Bernie Sanders, has embarrassed almost the entire American political ecosystem — pollsters, pundits, veteran political operatives and the talking heads who parrot their wisdom, focus-group entrepreneurs, super-pac strategists, number-crunching poll analysts at FiveThirtyEight and its imitators. But of all the emperors whom Trump has revealed to have few or no clothes, none have been more conspicuous or consequential than the GOP elites. He has smashed the illusion, one I harbored as much as anyone, that there’s still some center-right GOP Establishment that could restore old-school Republican order if the crazies took over the asylum.

The reverse has happened instead. The Establishment’s feckless effort to derail Trump has, if anything, sparked a pro-Trump backlash among the GOP’s base and, even more perversely, had the unintended consequence of boosting the far-right Ted Cruz, another authoritarian bomb-thrower who is hated by the Establishment as much as, if not more than, Trump is. (Not even Trump has called McConnell “a liar,” which Cruz did on the Senate floor.) The elites now find themselves trapped in a lose-lose cul-de-sac. Should they defeat Trump on a second or third ballot at a contested convention and install a regent more to their liking such as Ryan or John Kasich — or even try to do so — they will sow chaos, not reestablish order. In the Cleveland ’16 replay of Chicago ’68, enraged Trump and Cruz delegates, stoked by Rush Limbaugh, Laura Ingraham, Matt Drudge, et al., will go mano a mano with the party hierarchy inside the hall to the delectation of television viewers while Black Lives Matter demonstrators storm the gates outside.

Did the pillars of the Establishment fail to turn back the Trump insurgency because they have no balls? Because they have no credibility? Because they have too little support from voters in their own party? Because they don’t even know who those voters are or how to speak their language? To some degree, all these explanations are true. Though the Republican Establishment is routinely referenced as a potential firewall in almost every media consideration of Trump’s unexpected rise, it increasingly looks like a myth, a rhetorical device, or, at best, a Potemkin village. It has little power to do anything beyond tardily raising stop-Trump money that it spends neither wisely nor well and generating an endless torrent of anti-Trump sermons for publications that most Trump voters don’t read. The Establishment’s prize creation, Marco Rubio — a bot candidate programmed with patriotic Reaganisms, unreconstructed Bush-Cheney foreign-policy truculence, a slick television vibe, and a dash of ethnicity — was the biggest product flop to be marketed by America’s Fortune 500 stratum since New Coke.

While it’s become a commonplace to characterize Trump’s blitzkrieg of the GOP as either a takeover or a hijacking, it is in reality the Establishment that is trying to hijack the party from those who actually do hold power: its own voters. The anti-Establishment insurgencies of Trump, Cruz, and Ben Carson collectively won the votes of more than 60 percent of the Republican-primary electorate from sea to shining sea both before and after the opposition thinned. If you crunch the candidates’ vote percentages in the five states that voted on March 15, after Carson’s exit, you’ll find that Trump and Cruz walked away with an average aggregate total of 67 percent. The next morning, The Wall Street Journal’s editorial page, the leading Establishment voice of anti-Trump conservatism, saw hope in Kasich’s “impressive” victory in Ohio and Trump’s failure to break 50 percent in any state. It failed to note that Kasich also fell short of 50 percent in the state where he is the popular sitting governor, or that his continuing presence in the race perpetuates Trump’s ability to divide and conquer.

It’s debatable who or what can be called the Republican Establishment at this point. Presumably it includes the party’s leadership on the Hill and in the Republican National Committee; its former presidents, presidential nominees, top-tier officeholders, and their extended political networks; hedge-fund and corporate one-percenters typified by Paul Singer, Kenneth Langone, and the Koch brothers, mostly based in the Northeast, who write the biggest campaign checks; and the conservative commentators who hold forth on the op-ed pages of the country’s major newspapers, conservative media outlets like Fox News, and conservative journals like National Review, which devoted an entire issue to its contributors’ “Dump Trump” diatribes well after his runaway train of a campaign had already left the station.

Once you get past the hyperventilation that Trump will destroy democracy, wreck the GOP, and make America unsafe, you’ll see that the objections of Trump’s Establishment critics have several common threads. Trump is a vulgarian (true). He has no fixed ideology or coherent policy portfolio (true). He repeatedly and brazenly makes things up (true). He wantonly changes his views (true). He is not recognizable as “a real Republican” (false).

It’s the members of the Establishment who have a tenuous hold on the term “real Republican.” Their center-right presidential candidates of choice (Jeb Bush, Chris Christie) were soundly rejected, and their further-right candidates (Rubio and Kasich) fared little better. The Republican-primary voters embracing Trump and Cruz have every right to say that they are the real Republicans, and after Cleveland, they could even claim to be the de facto new Establishment, if they believe in such a thing. The old center-right has not held in the GOP. Last fall, some 73 percent of Republicans told Pew that they support building a border wall, Trump’s signature campaign issue. A Washington Post–ABC News poll, published March 9, showed that Hillary Clinton would whip Trump, 50 to 41 percent, but that 75 percent of Republicans would vote for Trump. While it is constantly and accurately said that “millions of Republicans will never vote for Trump,” those millions are unambiguously in the party’s minority.

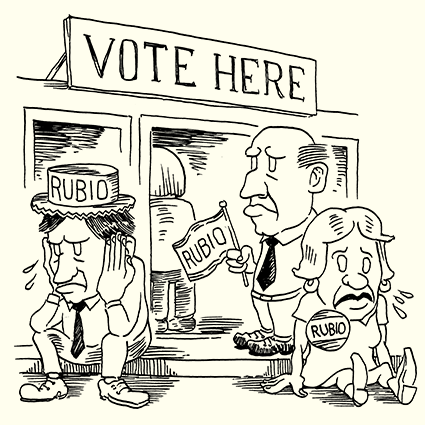

Battle Cry of the Elite

Marching to certain defeat (though keeping an eye on their career), Washington Republicans go to vote.

On Saturday, March 12, many younger Washington, D.C., Republicans probably didn’t realize that they were lined up across the street from the old 15th Street headquarters of the Washington Post, whose recently removed signage has left a dark smudge reminiscent of Richard Nixon’s five-o’clock shadow. The only polling place for D.C.’s GOP primary was the Loews Madison Hotel, a venue no doubt chosen some months ago, when about 300 voters might reasonably have been expected to show up. In the event, nearly 3,000 stood under the clouds and occasional light rain.

We’d come out to stop Trump, who ended up getting 14 percent of the vote to Rubio’s 37, Kasich’s 36, and Cruz’s 12 — a last Little Marco hurrah that, when even deemed worthy of notice, was only jeered as further proof of the Washington Establishment’s determination to overturn the will of the heartland. In fact, the District’s GOP voters — most of whom passed the time on line talking to others they knew personally — have never been an Establishment so much as a tiny infrastructure of operatives and appointees who can be summoned to life during those increasingly rare moments when a Republican administration needs to be assembled.

Throughout the afternoon, young people running to become uncommitted delegates — looking to mount the first rung of a ladder they don’t seem to understand has already been pulled away from the house, which itself has collapsed — importuned voters on the line. As someone who has already suffered enough political torment for one lifetime — supposed literary intellectual/homosexual/Republican — I was surprised by my own tetchiness, by the prosecutorial style of my questioning. “Is there any circumstance under which you would vote for Trump in Cleveland?” I’d ask. “I can’t imagine one,” would come the answer. “Not good enough,” I would reply, turning away and staring ahead with all the warmth of Nancy Reagan in the presence of some suitor her daughter had brought home.

Inside the hotel, where one had to crawl through an ever-thickening gauntlet of aspirant delegates on one’s way to the voting machines, a Trump volunteer awaited me with literature and arguments; I refused her my attention, let alone a handshake, which only made me realize that her candidate has affected not just my mood but also my manners. (What, by the way, do we call them? One friend says Trumpsters; another says Trumpkins.)

Greeting voters as they neared the final threshold was Josh Bolten, George W. Bush’s last chief of staff, who two days earlier had sent out a #NeverTrump e-mail appeal to “Bush-Cheney alumni in DC.” (I had served W. in various capacities at the National Endowment for the Humanities.) Sensing how the vote was going, Bolten told me he was having a great day.

Could either of us be blamed for enjoying the momentary repulsion of the Visigoths? Several blocks away, the Old Post Office, a McKinley-era pile where my NEH office used to be, has since 2013 been leased from the government, for a period of 140 years, by a certain private developer. Next January’s inaugural parade, whoever’s in the armored limo, will be passing the future home of the Trump International Hotel, Washington, D.C.

Illustration by Tony Millionaire

The charges that Trump is a “con man” and an ersatz Republican were particularly rich coming from Romney, who in typical regal fashion elected himself leader of the Establishment’s anti-Trump brigade. (His intervention failed to have any effect, even in his native state of Michigan.) Romney is a man who made up so many things in 2012 that his own pollster was moved to declare that “we’re not going to let our campaign be dictated by fact-checkers.” Much has been said about Romney’s hypocrisy in attacking as “a phony” and “a fraud” the man whose endorsement he brandished four years ago in an obsequious Las Vegas summit and whose business acumen he lavishly praised at the time. But no less phony is his holier-than-thou assault on Trump as a despoiler of the pure Republican faith given his own long history of political flip-flops and xenophobic hostility to immigrants.

As an unsuccessful Senate candidate in Massachusetts in the 1990s, Romney took stands well to the left of those in Trump’s past: He was a steadfast advocate for not only Planned Parenthood (his wife, Ann, made a contribution during campaign season) but abortion rights, and he promised to “provide more effective leadership” than his opponent, Ted Kennedy, in support of “equality for gays and lesbians.” As Massachusetts’s governor, Romney didn’t just endorse certain elements of government health care as Trump has; he pioneered what is now Obamacare. And as his policy gyrations match Trump’s, so, too, does his xenophobia. In 2012, he chastised his rivals Rick Perry and Newt Gingrich for expressing a few scintillas of humanity toward immigrants, reviled Rudy Giuliani with the bogus and racially loaded charge of turning New York into a “sanctuary city,” and coined the now-notorious term self-deportation. Romney’s nativism was all the more egregious given that his own father was an immigrant from Mexico, where he was born to American parents in a Mormon colony. (The legality of George Romney’s claim to qualify for the presidency as a “natural-born citizen,” like Cruz’s, went unresolved during his 1968 campaign.) If Trump is a counterfeit Republican, then Mitt is nothing if not the template for his forgery.

Romney and his Establishment peers have also made a big show of branding Trump a traitor to GOP values because he feigned ignorance of his fan David Duke and took his sweet time before disavowing Duke’s alma mater, the Ku Klux Klan. But just over a year ago the Republican congressman Steve Scalise of Louisiana conceded that he had committed an even greater infraction than Trump’s by speaking before a Duke-affiliated white-supremacy group in 2002. Scalise had been invited to do so by two longtime Duke aides, at least one of whom was a friend, but he nonetheless maintained, just as Trump did, that he had no idea who these people were or what they stood for. Even hard-line conservatives doubted Scalise’s story — Charles Krauthammer called it “implausible,” and Erick Erickson asked, “How the hell does somebody show up at a David Duke–organized event in 2002 and claim ignorance?” — but the incident was hardly an impediment to Scalise’s advancement in the GOP. He was rewarded with the No. 3 post in the House leadership, majority whip, which he retains today. That Scalise’s boss, Paul Ryan, would glom onto Trump’s Duke brouhaha as a cue to grandstand about how Republicans must reject all groups that traffic in bigotry — “There can be no evasion and no games,” he lectured—is as laughable as it is shameless.

The fiction that Trump’s exploitation of racial resentments is a shocking breach of Republican values has been fiercely asserted by Romney, Ryan, and the rest of the GOP Establishment for the obvious reason: A nearly all-white party, staring down the barrel of a looming minority-white America, can’t compete in national elections unless it can claim to have retained its founding identity as the party of Lincoln. That’s why there have been so many recent revisionist histories in conservative publications (not to mention a book by Joe Scarborough) attempting to sanitize the racial animus of the Goldwater-Nixon “Southern strategy” of a half-century ago. As voters went to the polls on Super Tuesday, March 1, Bret Stephens, a conservative columnist at the Journal who loathes Trump, captured the Establishment’s panic that Trump might now be sabotaging that elaborate airbrushing effort. “It would be terrible to think the left was right about the right all these years,” he wrote, and to discover that its “tendentious” accusations of “racial prejudice” were validated by Trump’s success among the Republican electorate of 2016.

One doesn’t need tendentiousness to make the accusation that some modern Republican leaders — and not just notorious southern racists of the Strom Thurmond and Jesse Helms ilk but the Establishment’s very own centurions — have courted, and still court, bigots much as Trump does. The facts speak for themselves. It was no accident that Ronald Reagan traveled from the 1980 Republican convention to give a speech on states’ rights to a virtually all-white audience just outside the small town of Philadelphia, Mississippi, best known as the site where the Ku Klux Klan murdered three civil-rights workers in 1964. Reagan was no Klan sympathizer, but, like Trump, he knew how to pander to voters who might be.

Reagan’s ostensibly more genteel, old-school-Republican successor, George H. W. Bush, was scarcely different when it came to playing the race card, though you’d never know that from the way he has been canonized lately to serve as a paragon of the Establishment-GOP values Trump has defiled. Bush opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in his first run for Senate in Texas because he thought it “trampled” the Constitution. When he first ran for president in 1980, he hired Charles Snider, the longtime campaign manager for George Wallace, the populist and racist demagogue who increasingly seems to be Trump’s role model. Eight years after that, Bush hired Thurmond’s protégé Lee Atwater to run his race-infected campaign against Michael Dukakis. (Atwater rhetorically linked Willie Horton, a black murderer and rapist featured in a pro-Bush pac’s ad campaign, to Jesse Jackson.)

The Destroy-the-Party-to-Save-It Plan

Gaming out a Trump win and loss with Bruce Bartlett, veteran of the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations.

Since the summer, you’ve been arguing that moderate Republicans like yourself should welcome a Trump nomination — and a general-election loss — as a way to reset the party. How’s that going? Well, it was a hope, not necessarily an expectation. But everything is pretty much on track. The thing I had been thinking about is, Okay, let’s take the point of view of an Establishment Republican, the sort of person who’s not terribly philosophical and just wants to win. You could deny Trump the nomination by playing dirty tricks, but he’s definitely going into the convention convinced, along with all of his supporters, that he’s the legitimate nominee. And you have to assume it can’t be taken from him legitimately, because there’s nobody to beat him! So it will have to be stolen. We know Trump can get on TV anytime he wants for as long as he wants. What would he do with his time for the next several months after the convention? Seems to me he’d use it to scorched-earth-destroy the party.

If you’re a party regular and believe he will lose badly, you’re mainly concerned with keeping this from destroying your party all the way down the ticket. One option would be to embrace Trump, hold your nose, and vote for him out of tribal loyalty. Another option, and this one I think is already in play, is, there will be a fairly substantial Republicans-for-Hillary push, on the theory that they’ll vote Republican down the ticket.

How far along is that right now? Michael Gerson, in the Post, is already basically saying the only options are to vote for Hillary or not vote. You’ve got neocons like Robert Kagan saying he’s going to vote for Hillary. And you’ve got Republicans running for House and Senate who are asking, “How do I avoid being dragged down by the guy at the top of the ticket?” They’re going to be running their own anti-Trump ads.

And how will a Trump loss restore the moderates to power? I can’t see Trump being a continuing presence in the Republican Party the day after the election. He’ll just go back to doing his business crap, right? I think he’s right that a lot of his support is coming from people he’s brought to the party, but I don’t see them hanging around and being the Trump wing. Look at Ross Perot — his people went and started the Reform Party, they didn’t stay in the Republican Party.

The question is: How do we pick up the pieces so that we can win in 2020? And where are the vulnerabilities? Republicans will have to come up with some strategy for getting votes from all the people they lost. It seems to me, at that point, the pollsters and the campaign consultants may say, “Look, I’m just as right-wing as you are, but ultimately we have to win.” That’s how they make their money.

We might see the equivalent of Blue Dog Democrats, the Democrats who run in red states and have to dis the party from time to time just to stay in office — there’s no equivalent on the Republican side. But there will be, there has to be.

Do you think today’s GOP bears any resemblance to the party when you a loyal member? Oh, I think it’s a completely different party. Any voter who was a moderate, let alone a liberal, has simply been banished. Many others who used to be actively involved at the local level simply aren’t anymore. They may still vote Republican regularly, but they don’t contribute to the party, they don’t go door-to-door. It’s like what happens with religion: People stop going to church, though they don’t stop calling themselves Catholics.

It’s going to have to be like after 1964, where the party Establishment says, “Look, we gave you your perfect candidate, and the guy lost!” After Goldwater, they went to an old face, they went to Nixon. And so the question is: Who is the Nixon standing in the wings?

Alex Carp

Illustration by Tony Millionaire

The next generation of this archetypal Establishment Republican dynasty has done its best to uphold the family tradition in a new century. George W. Bush journeyed to Bob Jones University to deliver a campaign speech in 2000, when it still banned interracial dating; that same year, he refused to support taking down the Confederate flag at the South Carolina statehouse in Columbia, where it had been raised in 1961 in resistance to desegregation. In 2015, his brother Jeb was slightly ahead of the curve of his major GOP presidential competitors in suggesting (gently) that the same flag be removed after the Charleston church massacre, but he still waited three days and acted only after Romney had done so more unequivocally. What separates Trump from such stalwarts of the Republican Establishment as the Bushes is that instead of perfuming his nativist or racial pandering with disingenuous phraseology like compassionate conservatism and kinder, gentler and right to rise, he dispenses with the niceties, or, as he would put it, is brave enough to be politically incorrect. Trump is hardly an outlier in a party that questioned Barack Obama’s citizenship from day one and that, eight years later, still regards him as an illegitimate president whose Supreme Court nominee is unworthy of even pro forma consideration by the Republican Senate leadership.

In trying to understand why smart Establishment-conservative commentators like David Brooks and Ross Douthat (at the Times) and George Will and Michael Gerson (at the Washington Post) so uniformly underestimated Trump’s appeal among Republican voters for so long, you have to start by assuming that they were in denial, as Stephens was, about how his baser instincts might appeal to some in their party’s angry base. But insularity may have played as big a role as denial. Most Republicans are not racists, and race is hardly the whole Trump story, yet it’s not clear that the elites got any of the story. Thomas Frank, writing in The Guardian, has mocked the liberal pundit Nicholas Kristof for devoting a column to a dialogue with an “imaginary” Trump voter rather than speaking to an actual one, but Establishment-conservative pundits may not have dug much deeper into their own grassroots.

Just how out-of-touch they are was broadcast late last summer by the National Review writer Ramesh Ponnuru, who, like Douthat and Gerson, is part of the so-called reform-conservative coterie, eager to remake the GOP so it might speak not just to the needs of the business-ownership class but to middle-class Americans (rather like many of the voters Trump has been attracting, paradoxically enough). For Bloomberg View, Ponnuru compiled a list of bullet points to explain why Trump had no chance of winning the GOP nomination: “too many of his supporters are just registering discontent before they make a real decision several months from now”; “Republican elected officials would consolidate behind a consensus choice if Trump started winning delegates”; “the decisive Republican presidential primary voters are a pretty sober-minded bunch.” This sounds like the kind of thinking Marie Antoinette must have entertained before being marched to the guillotine.

It’s hard to believe now, when the bar has fallen so low that merely being “an adult” is enough to make Kasich the class act of the Republican debate stage, but back at the start of this election cycle, virtually the entire conservative-Establishment commentariat was touting the large Republican field as Olympian: “the most impressive since 1980, and perhaps the most talent-rich since the party first had a presidential nominee, in 1856” (George Will). None of these elites could believe that Trump would get anywhere, given all the fabulous alternatives bestowed on the benighted voters. And surely everyone would love Rubio — the oft-described “future of the party” — whom the Establishment started hawking once its natural favorite, Jeb!, failed to launch. Rubio is “a genius at relating policy depth,” Brooks wrote in September, days after predicting that Trump and Carson “will implode.” In October, he declared Rubio “the most likely presidential nominee” and noted that while “disaffected voters” were turning to Trump, “there aren’t enough of those voters in the primary electorate to beat Rubio,” who “has no natural enemies anywhere in the party.” After the Iowa caucus in February, Brooks wrote that “the amazing surge for Marco Rubio shows that the Republican electorate has not gone collectively insane.” Rubio may have come in third in Iowa, but what did that matter, given his “growing Establishment base”?

By then the elite pundits were reduced to begging Republican voters to heed their gravitas. Brooks and Stephens wrote twin columns respectively pleading “Stay Sane America, Please!” and “Sober Up, America.” But it wasn’t America they were asking to sober up — it was the rank-and-file of their own party, whose impertinence and independence have blindsided and baffled them. Gerson, a former Bush 43 speechwriter who has taken to likening Trump to the end of civilization as we know it, wrote an early-March Post column proposing this antidote: “#DraftCondi.” Who was this Hail Mary pass being pitched to, exactly — fellows at the American Enterprise Institute? Why would Republican voters who had rejected Bush, Christie, and Rubio — all of whom embraced George W. Bush’s discredited national-security team for foreign-policy advice — do anything other than laugh at the Establishment fantasy of a Condoleezza Rice revival? If nothing else, Gerson verified a point that Jacob Heilbrunn, the editor of the National Interest, made in Politico: “In debunking the GOP’s hollow men and bringing the Bush-Cheney era to a close, Trump is essentially kicking in a rotten door.”

If Trump has one indisputable talent, it’s for spotting the weakness in others (though not himself). In the GOP Establishment, he saw a decadence that he has targeted as relentlessly as he did Jeb’s “low energy.” As far as I can tell, the only Establishment-conservative pundit who had a clue that Trump was taking root (and why) has been Peggy Noonan of the Journal, who made a point of talking to Trump voters. Noonan made a fool of herself on the eve of 2012’s Election Day when she saw intimations of “a Romney win” in a profusion of Romney lawn signs in Ohio, Florida, and “tony Northwest Washington, D.C.” She learned from her mistake. In December, she summed up what was happening this time as well as anyone: “The Establishment thinks they are saving the party from vandals, from Trumpian know-nothingism. But Republicans on the ground think those in the Establishment were the vandals, with their open borders, donor-class interests and social liberalism.” (Two of these three charges overlap with Bernie supporters’ discontent with the Clinton Establishment’s devotion to free trade and other donor-class interests.)

The elites’ ill-fated promotion of Rubio, who never got any serious traction beyond newspaper columns even before he self-immolated with urination and dick jokes, illustrates this. They gambled that Rubio would fly with the base because he’s an unalloyed conservative and anti-abortion extremist whose smooth façade of seeming moderation would make him more “electable” than the oily Cruz, whose political views (and high ratings from conservative interest groups) he almost entirely duplicates. Rubio’s brief showboating flirtation with Gang of Eight immigration reform damaged him more than Cruz’s similar but less public apostasy, not just because it put him briefly in league with Chuck Schumer but also because it linked him to the same tarp class of fat-cat contributors who tainted Bush and Christie. Among Rubio’s prominent backers was Paul Singer, who has contributed heavily to groups backing causes Rubio decidedly does not—immigration reform and legal same-sex marriage.

To the GOP base, associating with what culturally might be called the Romney set is at least as big a sin as palling around with Schumer. In his devastating populist put-down of Romney in 2008, Mike Huckabee described himself as a prospective “president who reminds you of the guy you work with, not the guy who laid you off.” That caricature of Romney — which was hammered in by Gingrich, who tried to take him out in 2012 with a full-bore vilification of “vulture capitalism” at Bain — more or less applies to every Establishment figure or donor associated with Rubio, Christie, Bush, and Kasich. That Trump, who’s literally made a show of firing people on national television, escapes this stain is a testament to the power of his crude everyman shtick. Unlike such Republican billionaires as the Koch brothers and Stephen Schwarzman, Trump would never be caught embossing his name in fancy fonts on elite cultural palaces like the Lincoln Center home of the New York City Ballet or the New York Public Library. He earns proletarian cred by instead stamping his own name in gold caps on cheesy buildings that he claims to have built himself.

The Republican elites’ complaint that Trump’s politics, to the extent that his politics can be defined, would change those of their party is a red herring. The GOP is and will be mostly conservative; the percentage of Republican voters who call themselves “very conservative” has jumped from 19 percent to 33 percent since 1995. Even an ostensibly less-conservative Republican like Kasich is an abortion absolutist who defunded Planned Parenthood in Ohio and is a foe of both regulating carbon emissions and tightening gun laws. Trump’s deviation from party orthodoxy on free trade, preserving entitlements, and, perhaps, social issues won’t change the party’s ideological profile (though it may bring in more Democrats, independents, and new voters than a Cruz or Rubio ever would). His outlandish positions on immigration, torture, barring Muslims, and fighting isis are just crasser iterations of his opponents’ calls for turning away Syrian refugees, building their own border walls, repealing the “birthright citizenship” bestowed by the 14th Amendment, carpet-bombing the Middle East, and expanding Guantánamo.

For all the Republican talk about “personal responsibility,” the party’s leaders have worked overtime to escape any responsibility for fanning the swamp fevers that produced Trump: They instead blame him on the same bogeymen they blame everything on — Obama and the news media. What GOP elites can’t escape is the sinking feeling that a majority of Republican voters are looking for a president who will repudiate them and, implicitly, their class. Trump refuses to kowtow to the Establishment—and it is precisely that defiance, as articulated in his ridicule of Romney and Jeb Bush and Megyn Kelly and Little Marco, that endears him to Republican voters and some Democrats as well. The so-called battle for the “soul” of the Republican Party is a battle over power, not ideology. Trump has convinced millions of Americans that he will take away the power from the pinheads on high and return it to people below who feel (not wrongly) that they’ve gotten a raw deal. It’s the classic populist pitch, and it will not end well for those who invest their faith in Trump. He cares about no one but himself and would reward his own class with extravagant tax cuts like any Republican president. But the elites, who represent the problem, have lost any standing that might allow them to pretend to be part of the solution.

So what is the embattled GOP Establishment to do? On Super Tuesday morning, Ross Douthat, who had long foreseen a Rubio victory and Trump collapse, offered this tweet: “The forces that Trump is pandering to/unleashing will prevent him from ever consolidating elite conservatives. Period.” But I suspect a more accurate prediction of what’s to come could be found in Rupert Murdoch’s tweet the next afternoon, following Trump’s latest multistate victory: “As predicted, Trump reaching out to make peace with Republican ‘establishment.’ If he becomes inevitable party would be mad not to unify.” Murdoch’s use of scare quotes around Establishment is appropriate: It barely functions now, and the pretense of its existence is unlikely to survive Election Day.

The conventional wisdom that Trump is “destroying” the GOP may prove as wrongheaded as the assumption in 1964 that Barry Goldwater had done the same. Win or lose, Trump, like Goldwater, may be further hastening the party’s steady consolidation rightward. For all their blustery threats of third-party campaigns, defections to Hillary, and other acts of rebellion, Republican elites in the political game are more likely to bend to Trump than the other way around, no matter how many conservative op-ed columnists beg them not to do so. They still want to preserve any shred of power they can, and to do that, they must pitch in and try to win. You’ll notice that just about the only Republican politicians or campaign operatives who are vocal in the #NeverTrump claque are either congressmen who are retiring this year, party potentates who have long been out of power (Christine Todd Whitman, Ken Mehlman, J. C. Watts, Mel Martinez), or, as Trump would say, losers (anyone who served in the campaign hierarchies of Romney or Jeb, any neocon who served as a Bush-Cheney architect of the Iraq War). Everyone else will keep on doing what senators and governors like Orrin Hatch and Jeff Sessions and Paul LePage have steadily been doing: They will appease Trump or surrender to him altogether on the most favorable terms they can, for “the good” of the party and the ticket in November. They will make their peace with the art of the deal.

*This article appears in the March 21, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.