It was easy to love Ryan Murphy’s The People v. O.J. Simpson — the whole thing was a blast, from the Marcia Clark revival to David Schwimmer skewering the Kardashians. And though it played history as camp, most of the time, ultimately, that didn’t matter: The history was so rich we couldn’t help but take it seriously, even when it was fed to us as a popcorn reenactment.

Which is why O.J.: Made in America, I guarantee you right now, is going to blow your mind. The documentary, which screened at Sundance this winter and last month at Tribeca, runs seven hours and 43 minutes. It was made under ESPN’s 30 for 30 banner and, after a brief theatrical run (probably to qualify it for an Oscar), will air in prime time, on ABC and ESPN, starting June 11. It will be the only thing this country’s going to be talking about that whole week.

Directed by Ezra Edelman, O.J. is massive but never sprawling, passionate but never unfair, informative but never anything but compulsively entertaining. By devoting nearly eight hours to the trial and all that surrounded it, Edelman is able to give a true, and truly operatic, 360-degree treatment of a story that basically nobody has ever before been able to process except in pieces. There was the way the trial was viewed so differently by black and white audiences, of course, but also all the aspects that could be appreciated only by smaller groups — those savvy about race in American sports, those crusading to make domestic violence an unoverlookable national horror story, those who knew the celebrity cult of Los Angeles and its tabloid-economy underbelly, those who appreciated the coming of reality television, and those who saw the terrible naïveté of a country trying to reckon with centuries of racial injustice by turning the trial of a single man into a national morality play. Simpson’s trial was always bigger than him, bigger than sports, bigger than celebrity, bigger than anyone realized at the time. It has taken 21 years for someone to capture what the trial was really about— everything it was about.

In Edelman’s hands, nothing gets short shrift — that’s partly the beauty of having an eight-hour cabinet to fill with stuff and partly the beauty of the stuff itself. Edelman has unearthed some truly breathtaking footage — including Al Cowlings breaking down while giving the eulogy at Nicole Brown Simpson’s funeral; O.J. screaming about the television coverage of his trial at a post-acquittal party; and even a shocking scene featuring present-day, bloated, defeated O.J. talking about prison to a parole board. But the movie is most powerful for its scope, its ability to show how the Simpson trial reflected (and even shifted) national attitudes toward fame, and sports, and television, and media, and L.A., and science, and, of course, race. We’ve been talking about this case for more than two decades, but it’s not until you watch Edelman’s film that you realize how much of that talk has been empty chatter — slivers of the talk we should’ve been having. More than anything else, it builds a profound, almost overwhelming case that O.J.’s acquittal in 1995 may have been one of the biggest civil-rights victories of the entire decade. The verdict was just cause for all that national celebration from African-Americans, even if he was guilty. Shit, especially if he was.

O.J. does not pretend, by the way, that O.J. was innocent; if the detailed history of Simpson’s brutal abuse of Nicole wasn’t enough, a horrifying 15-minute segment in which former prosecutor Bill Hodgman coldly lays down precisely how Simpson butchered Nicole and Ron Goldman will remove any lingering doubts. But it reminds us of the evil of Mark Fuhrman — who appears in the film, older but mostly unchastened — and also of how he was less an outlier in the LAPD than a symptom. The movie sees all sides with a clarity most Americans lacked at the time … and have lacked since. The verdict might have been bullshit. That doesn’t mean, in its own way, it wasn’t a grand victory.

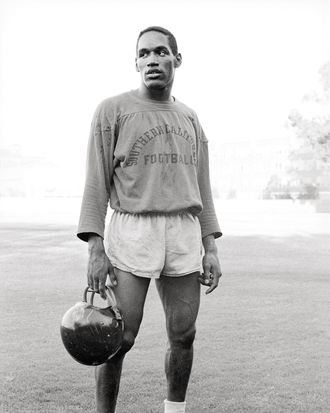

And what about the men who won it? In O.J., we see Simpson as the awkward civil-rights hero he was — a man who scrupulously avoided, for his whole career until the murders, the political struggle that ran parallel to his rise, famously saying, “I’m not black, I’m O.J.” (When he was first escorted to jail, on seeing all the African-Americans who showed up to support him, he said, “What are all these n—-rs doing in Brentwood?”) We also see how Johnnie Cochran, far from being an opportunist, truly believed that putting the LAPD on trial on the largest stage possible was the most important work of his life. Which, despite a long and laudable career before O.J., it probably was.

In the Seinfeld era, Cochran was seen by white America as a cartoonish grandstander. In Ryan Murphy’s pageant version, Courtney B. Vance mostly restored his dignity, with a few delicious comic flourishes. But as we see in the documentary footage, the real Cochran didn’t need any rehabilitation. Nor did his “grandstanding.” Edelman convinces us of this by focusing almost as much on the LAPD as he does on Simpson. We get the full history of the city’s scabrous racial politics, from the southern blacks who came to Los Angeles expecting acceptance and discovering something far different, to the Watts riots, to the death of 15-year-old Latasha Harlins, to former LAPD chief Daryl Gates’s horrific racial attitudes, including his infamous claim that more black men were dying from chokeholds because their arteries “do not open up as fast as they do in normal people.” It all exploded with the Rodney King riots, which were less about King and more about the seeming impossibility that a black man could ever win anything in a court of law in the city of Los Angeles. If O.J.— with all his lawyers and all his money — couldn’t beat that system, what hope would there ever be for anyone else?

The joke, of course, is that while African-Americans were all celebrating O.J.’s eventual acquittal, whites were mortified by it. “Blacks are extraordinarily skeptical that the system can be fair, while whites see the system as essentially color-blind,” the political scientists Jon Hurwitz and Mark Peffley, authors of Justice in America: The Separate Realities of Blacks and Whites, have said. In their research, “while about 25 percent of whites disagreed with the statement that the ‘courts give all a fair trial,’ more than 60 percent of African-Americans disagreed.” O.J. is full of footage of blacks and whites reacting to the verdict in diametrically opposite ways, and the genius is that you absolutely understand why both sides were sort of right.

The film is also, in a quiet way, an argument for our times — and even, if you can believe it, a tribute to the way we talk to and understand each other now. Marcia Clark and the prosecution didn’t just underestimate how much race would be a factor in the trial — top to bottom, from their reliance on Fuhrman to their jury selection to just about everything Christopher Darden went through during the whole trial, they didn’t even seem to recognize that race would matter. It was something that white people, well-meaning and otherwise, simply could not understand, because it was something they hadn’t been exposed to. I was in college in central Illinois when the verdict came down, and like every white person I knew — and I almost exclusively knew white people — I was appalled that O.J. had been acquitted and baffled that anyone would celebrate it. But I’d understand it today.

And the reason I’d understand it is that, like everyone else, I hear from so many more voices now — so many more people of color, people who understand what life in L.A. has been like for black people for decades. We often think the social-media era closes each of us off into ideological echo chambers — which is, in part, true. But what’s echoing within those chambers are often contrary opinions, circulated via outrage. A midwestern white Republican in 2016 might not have much sympathy for Black Lives Matter, but he’s not shocked when the death of a civilian in a police shooting is followed by protests. Obviously, sometimes — most of the time! — we use this ability to have a voice as a way to scream at one another. When we see it all day, every day, it can look like nothing but ugliness. But that doesn’t mean that’s not, in its own way, a sort of progress. Marcia Clark damn sure wouldn’t be so surprised today, at least.

*This article appears in the May 2, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.

Now Watch: LeBron James Cheering On His Kids On The Basketball Court Is A Thing To Behold