In a modestly air-conditioned office space in a suburban strip mall in Arlington, Virginia, the Hillary volunteers are phone-banking. They are gathering around card tables and crammed into sofas and loveseats, beneath handmade signs and patriotic bunting, mostly retirees and college students, talking on cell phones and filling out paperwork, pinching the microphones of their headphones between thumb and forefinger and clasping their hands over their ears.

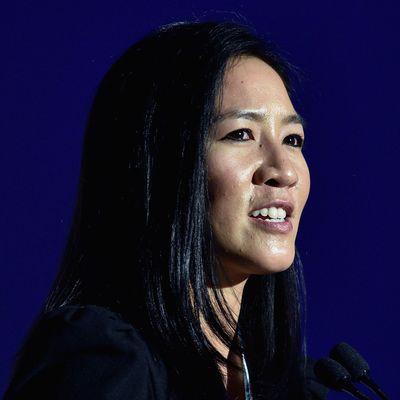

At the center of the scene is Michelle Kwan, 36, the legendary Olympic figure-skating medalist. Her hair is shorn in a long summer bob, and she’s wearing a black dress with a tulip skirt paired with black ankle-strap heels. A small group of volunteers, breaking for a moment to meet their celebrity guest, cautiously hovers around her. “I am so nervous right now,” one woman says, stepping forward to ask for a picture. “My sisters are so jealous.” Kwan smiles and says, “Aww, where are they from?”

It’s a phenomenon that goes back to the first Clinton administration and was only reinforced during the Obama years: The Democratic party now relies on a constellation of stars among its key supporters and surrogates. The new center of this nexus of politics and celebrity in 2016 is Michelle Kwan, who has the unique role of being both celebrity surrogate and Clinton campaign staffer. Kwan’s official role with the campaign is “surrogate outreach coordinator,” which basically means it’s her job to wrangle Clinton’s high-profile backers, including stars like Katy Perry, Lena Dunham, and Meryl Streep, all of whom have made appearances this year on behalf of the candidate. It cannot hurt that Kwan is also one of them. As best I can tell, the Trump campaign has no equivalent. (When I emailed a Trump campaign spokesperson to ask whether the campaign had a surrogate outreach coordinator, she wrote back, “Thanks. We will pass on this,” as though I was offering myself up for the role, rather than asking a yes-or-no question.)

“It’s easy to identify people who are supporters,” says Kwan, who searches social-media sites looking for famous people who have tweeted supportive things about Hillary Clinton and reaches out on behalf of the campaign. “There are a number of ways you can get involved,” she tells them, “from tweeting your support to traveling to a state to campaign for her.” Proximity to celebrity is a part of the Clinton campaign strategy to show a more personal side of the candidate to her younger viewers (see, for example: Clinton’s sit-down interview with Lena Dunham, or her walk-on cameo on Broad City) and Kwan says she’s been amazed by the number of famous people willing to get out and stump for Clinton. Demi Lovato traveled for her in Iowa. Scandal’s Tony Goldwyn headlined the campaign’s office opening in Atlanta. Justin Timberlake and Jessica Biel opened their home for a Clinton fundraiser last week, crammed into a photo booth with her, and posted the pics on Instagram.

Kwan is also unique in the way she inspired a generation of American women and girls, and there’s a parallel set of emotions the Clinton campaign has tried to capture as Hillary appears poised to become the nation’s first female president. At least, that’s the sentiment on display among the Clinton supporters at the phone-banking event, where a young woman with curly blonde hair looks up from her call logs and asks Kwan, “When I was in the fifth grade, I watched your long programs on VHS tapes. Do you still skate on occasion?” And an older woman jumps in: “Do you have any children?”

Kwan explains that no, she doesn’t skate much anymore, and no, she doesn’t have any kids — she married her husband, Clay Pell, a Coast Guard reserve lieutenant and former education-department official, three years ago. As Kwan gets pulled away by other well-wishers, the young woman tells the older one that she used to host Super Bowl–style events to watch Kwan perform, and asks her, “Are you a big figure-skating fan?”

“Huge,” the woman says. “I mean, I used to tear up when she would go into her spiral. I used to get sick for her. I’d have the TV on and my daughter would be next to me and I would close my eyes and say, ‘Tell me, did she land it? Tell me!’ I’d get so nervous. There’s just been nobody since who has that joy,” she sighs in the direction of Kwan, who is standing three feet from her.

Soon, a campaign videographer wearing seafoam Bose headphones asks Kwan to join him in the back of the room to film a video for the campaign. In the corner of the room they squeeze in next to snack shelves loaded with granola bars and bottles of Tabasco and Keurig coffee pods and start their interview. Kwan used to be the recipient of millions of dollars in endorsement deals, but she is, somewhat charmingly, not the perfectly polished media professional you might expect, and she proceeds to repeatedly screw up her intro, cracking herself up each time.

“Say your name and what you’re doing,” the videographer, whose name is James, instructs.

“I’m Michelle Kwan. What am I doing? I — sorry!” she bursts out laughing. “What am I doing?!”

“You can do this as many times as you want,” James says.

“I’m Michelle Kwan, former — not former — Olympic figure skater, and I’m the surrogate outreach coordinator,” she tries again.

“Hi, I’m Michelle Kwan, Olympic figure skater, I am the — this is so hard!” she cracks up again.

When they finally finish, James says, “We’ll make sure you get the video.”

“I don’t need to see it!” she laughs.

Politics was not, obviously, Michelle Kwan’s dream career growing up. That would be figure skating, and even by the standards of the profession, she accomplished a tremendous amount at a very young age, winning her first world championship at the age of 15 in 1996. By 2005, she’d become a two-time Olympic medalist, five-time world champion, and nine-time national champion. Though she was the dominant figure skater of her time, the gold medal alluded her, and Kwan withdrew from the 2006 Olympics after an injury. That same year, she was appointed as a public-diplomacy envoy — a kind of surrogate on behalf of the United States — for the State Department. In the role, she traveled to countries like Russia, Argentina, and Singapore, meeting with people and promoting cross-cultural dialogue as a goodwill ambassador. Kwan continued the role into the Obama administration, getting both undergrad and graduate degrees in international relations and political science, and she joined the State Department in a formal capacity in 2011 as a senior adviser for public diplomacy and public affairs. In 2014, her husband (the grandson of Senator Claiborne Pell, the guy responsible for Pell grants) ran for governor of Rhode Island. His bid was unsuccessful, but for Kwan, who played a big role in the campaign, it only reinforced her love for politics — and competition. “It was the most amazing experience,” says Kwan, who knocked on doors and hosted her own events across the state, coming in fifth in the campaign’s internal ranking of field organizers. “I was crushing it!”

Kwan watched as friends and colleagues moved to New York to lay the groundwork for Clinton’s bid last year, and when Clinton formally announced her campaign, she jumped at the chance to get involved. “There was no way that I could sit on the sidelines and watch it without getting involved. It was a very quick decision,” she says.

Now, Kwan spends most days at Hillary’s campaign headquarters in Brooklyn. But when she’s not there, she’s traveling the country for Clinton as a surrogate herself. After the phone-banking event, Kwan heads over to the official launch of Virginia’s Asian American Pacific Islanders for Hillary group at a pan-Asian Thai restaurant called Tara Temple. There, she is fully in star-surrogate mode. Outside the restaurant, she’s stopped by a handful of Virginia Democrats who enlist her to film a short video clip with a local official saying, “We are stronger together!” — one of the Clinton campaign’s slogans. After gamely going through about ten takes, Kwan walks into the happy-hour event. The inside of Tara Temple is decorated to give off Thai beach vibes, but the crowd is unmistakably Washington: women in smart business-casual, girls in sundresses, and middle-aged men in plaid shorts surround Kwan, a sea of grinning faces fixed on her, stumbling to give her about a foot of personal space while clutching their phones and waiting for their turn to take a photo.

After 30 minutes of this, Kwan steps up on one of the vinyl-upholstered benches in the corner of the room and is introduced by a local organizer to the crowd. “As I have been on the campaign trail now for over a year, every day I’m reminded about my personal story, about what’s at stake in these elections. I think of my parents, and as I look around the room, we probably share similar stories, of how our parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents might have immigrated to the U.S. … I often think, what’s the motivation for Hillary Clinton? It’s so the next generation of Americans have the ability to dream that dream,” she says.

As Kwan speaks, the crowd is silent, craning their necks to look up at her. A woman in an orange silk jacket slips to the front of the scrum and turns around to mug for photos in front of her. “I don’t want to regret this campaign. There’s so much at stake. I don’t want you to regret that 83 days from now you’re packing your bags and moving, okay?” Kwan says. The crowd starts to laugh, then cheer. “We’ve gotta do this!”

After she finishes speaking, she steps off the bench and sits for a moment. “It’s emotional, this journey,” she tells me. “There’s so much to do, and it’s overwhelming at times. But you just keep at it and you push through. It’s exciting, too!” She stands up and is swallowed by the crowd again.