“I’m on the battlefield right now, which is amazing,” Donald Trump said as he surveyed the Gettysburg National Military Park. “When you talk about historic, this is the whole ballgame.” It was the afternoon of October 22, and Trump was speaking by phone shortly after delivering a speech at the place where Lincoln pledged to unite a divided country. Trump had used the same location to pledge lawsuits against the women accusing him of grabbing them by the pussy. “I feel really good,” Trump continued, making his way to the motorcade to leave for the campaign’s next rally, in Virginia. “We had three polls this week that came out where we’re No. 1. I think we’re going to have a very big surprise in store for a lot of people.”

Even given the October surprise of the FBI’s reviewing a new batch of emails that may be related to Hillary Clinton’s use of a private server, Trump still faces difficult odds. But he is ending the race much as he got into it: not worrying too much about the future and not listening to any of the advisers around him. In recent weeks, I spoke with more than two dozen current and former Trump advisers, friends, and senior Republican officials, many of whom would speak only off the record given that the campaign is not yet over. What they described was an unmanageable candidate who still does not fully understand the power of the movement he has tapped into, who can’t see that it is larger than himself.

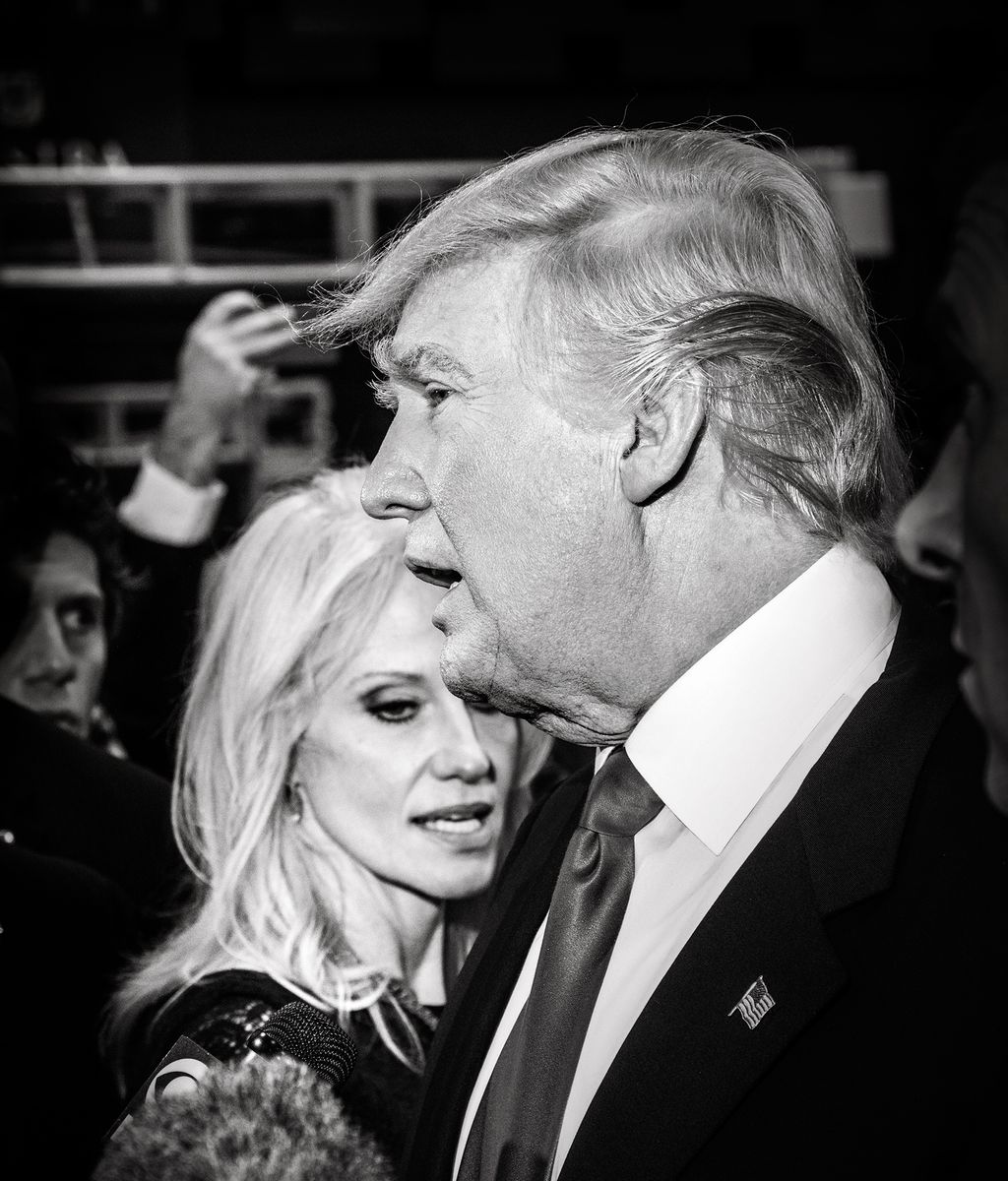

“I got really mad at him the other day,” Trump campaign manager Kellyanne Conway told me. “He said, ‘I think we’ll win, and if not, that’s okay too. And I said, ‘It’s not okay! You can’t say that! Your dry-cleaning bill is like the annual salaries of the people who came to your rallies, and they believe in you!’ ”

Trump may not be all that focused on what happens to the masses of white, nativist, working-class voters who have coalesced around him, but there are people in the campaign who recognize how valuable those Trump believers could be long after the election is over. As Bloomberg Businessweek recently reported, Trump’s son-in-law–cum–de facto campaign manager Jared Kushner is building a proprietary database of some 14 million email addresses and credit-card numbers of Trump supporters. That list could form the foundation of a new Trump media company. According to one Republican briefed on the talks, Kushner has approached Wall Street bankers and pitched ideas for media start-ups. “How do we monetize this?” he’s asked. (Through a spokesperson, Kushner denied having such meetings.)

Campaign CEO Stephen Bannon, who is taking a leave of absence from his role as executive chairman of Breitbart News to work with the Trump team, has an even bigger ambition for all those voters: reshaping the GOP and future elections. “The main goal for Steve was dealing a devastating blow to the permanent political class,” Breitbart editor-in-chief Alex Marlow told me. “It’s pretty clear he’s upended the Republican Establishment, so it’s a huge win for Steve’s ideas and for Breitbart’s ideas.” If the Republican Party of the past was full of rich fiscal conservatives who benefited from free trade, low taxes, low regulation, and low-wage immigrant labor, Bannon envisions a new party that is home to working-class whites, grassroots conservatives, libertarians, populists, and disaffected millennials who had gravitated toward the Bernie Sanders campaign — in other words, Trump supporters.

It’s clear that this until-now-underserved group has tremendous potential, both commercially and politically. But Trump doesn’t seem to know what to do with them beyond stoking their anger. In terms of the future, he is falling back on what he knows, bolstering the businesses that have suffered during the campaign. In recent days, Trump has dragged the national press corps to his new Washington hotel and his Miami-Dade golf course, essentially turning the campaign into a giant infomercial for his luxury properties. “Our bookings are doing great!” he told me. “The political involvement has made my clubs hotter because of this avalanche of earned media.”

The paradox is that Trump’s political brand and his commercial brand are very much at odds. “The people who are passionate about his brand can’t afford it right now,” a real-estate executive who knows Trump told me. And those who can afford it are less likely to want to be associated with his name. “He might have to go into multifamily rentals. Maybe he could put gold fixtures in a trailer park,” said the executive.

In the end, whether he figures out how to change his business model and capitalize on his followers hardly matters. “Trump is the vehicle,” Marlow said. Now there is momentum, with or without him.

Perhaps the most surprising thing to ponder at this late stage in the election is just how close the race could have been had he taken nearly any of the advice offered to him by advisers. “This thing was doable if we did it the right way,” one adviser told me.

When Paul Manafort, a veteran Republican lobbyist and operative cut from Establishment cloth — he’d worked on Gerald Ford’s, George H.W. Bush’s, and Bob Dole’s presidential campaigns — came onboard to serve as campaign chairman at the beginning of the general-election season, he suggested a strategy that was the exact opposite of the one Trump pursued in the primaries. He wanted Trump to lower his profile, which would force the media to focus on Clinton — a flawed opponent with historic unfavorable ratings who couldn’t erase the stain of scandal, real or invented. “The best thing we can do is to have you move into a cave for the next four months,” Manafort told Trump during a meeting. “If you’re not on the campaign trail, the focus is on her, and we win. Whoever the focus is on will lose.”

As is typical with most campaigns, Manafort wanted the Trump team to perform opposition research on its own candidate, so that the team would know what to be worried about and how to prepare for it. Manafort had known Trump since the ’80s and had heard rumors about his behavior with women, according to a source. He wanted to know what was out there. But Trump — perhaps believing that the Clinton campaign would never bring up women for fear of the specter of Bill’s past, or perhaps believing that it wouldn’t matter if they did (the “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody” hubris) — declined. The only information the campaign had to go on was the research the RNC had done into all of the candidates’ public statements.

In late April, Manafort assured RNC members that Trump would pivot to a more presidential “persona.” And for a while, it worked. Trump began using a teleprompter, cut back his TV appearances, and (mostly) avoided courting scandal. His poll numbers climbed, until he was tied with Clinton.

But asking Trump to not be the center of attention is like asking him not to breathe. “His ego couldn’t handle it,” said one Republican close to the campaign. “Hillary understood that Trump needed to be the focus.” As his poll numbers climbed, Trump felt he didn’t need to listen to Manafort. “The worst part about Trump is when he was ahead,” the prominent Republican said. “He’d get into the lead and then he would veer off and start defending his interests and his honor and it had nothing to do with what people actually care about. He’s not disciplined.”

In early July, Manafort recruited then–Fox News chairman Roger Ailes to advise Trump on debate prep and the staging of the Republican National Convention. (He also tried to get Apprentice creator Mark Burnett to chip in, but Burnett declined.) According to a Republican briefed on the meeting, Ailes attended a session at Trump’s penthouse shortly before the RNC, but “Donald wanted to talk about anything but the debates.” Ailes did suggest that Trump make an appearance at the convention every night to create drama, which he did. (Reached for comment, Ailes lawyer Susan Estrich said: “Roger has been friends with Donald for 30 years and has offered informal advice from time to time.”)

Trump got a post-convention bounce and was ahead of Clinton by a point. “What he needs to do,” Newt Gingrich told me, “is focus on the big issues.” Instead he got sidetracked on something any political operative could have told him was a losing battle: feuding with the bereaved Muslim-American parents of a soldier who had died in Iraq.

“You do know you just attacked a Gold Star family?” one adviser warned Trump.

Trump didn’t know what a Gold Star family was: “What’s that?” he asked.

To Trump, Khizr Khan and his wife, Ghazala, were enemies who had said something mean about him, just like Rosie O’Donnell and any number of people who had gotten under his skin over the years. Wasn’t it his right to respond?

“ ‘The election is about the American people, it’s not about you,’ ” Manafort told Trump, according to a person briefed on the conversation. Trump countered with Breitbart’s report on Khan’s purported belief in Sharia. “ ‘He’s not running for president,’ ” Manafort shot back. “ ‘The Clintons did this to us to waste our time getting off message.’ ”

With his poll numbers back in a downward spiral, Trump got an earful from one of his larger backers, the hedge-fund billionaire Robert Mercer, at a Hamptons fund-raiser in mid-August. Mercer complained to Trump that the campaign was in disarray, a source briefed on the conversation said. During a debate-prep session the following day in Bedminster, New

Jersey, Trump took it out on Manafort in front of senior advisers, including Ailes. “He complained Paul was not able to get the media to focus on the right stuff,” one attendee recalled.

Ailes, who had by this point been ousted from Fox News in a sexualharassment scandal, grew tired of Trump’s unwillingness to focus on the debates and drifted away from the campaign, according to sources close to Ailes. “He hasn’t been involved,” Trump confirmed. “I’ve maybe had two calls with Roger in the last two months.”

Manafort, too, would soon resign, having become the kind of distraction he was often warning Trump away from. Damaging reports of his lobbying ties to the Kremlin were making Trump’s pro-Putin statements look worse than ever. Besides, it was clear that Manafort had lost the trust of his candidate.

“Paul Manafort didn’t understand him,” a longtime Trump confidant told me. “Trump is going to do whatever the fuck he wants. You have to trick him into doing what you want.”

No one understands this better than Manafort’s successors. To hear Kellyanne Conway talk about managing her boss is to listen to a mother of four who has had ample experience with unruly toddlers. Instead of criticizing Trump’s angry tweets, for instance, she suggested that he also include a few positive ones. “You had these people saying, ‘Delete the app! Stop tweeting!’ ” she recalled. “I would say, ‘Here are a couple of cool things we should tweet today.’ It’s like saying to someone, ‘How about having two brownies and not six?’ ”

Conway had grown close to the Trumps, especially Ivanka, through a connection to the Mercer family. During the primaries, Conway had run a pro–Ted Cruz super-pac, which the Mercers had funded; after Cruz dropped out, she started advising Trump. The key to managing Trump, she told me, is to let him feel like he is in control — always. “It all has to be his decision in the end,” she said. A Trump donor explained it this way: “Trump has the following personality: NIH-NFW, meaning ‘If it’s not invented here, not invented behind these eyes, then it’s no fucking way.’ ”

When she was promoted to campaign manager in mid-August, Conway met with Trump in his office on the 26th floor of Trump Tower. She told him two things: that he was losing and that he was running a joyless campaign. “What would make you happier in the job?” she asked.

“ ‘I miss flying around and giving rallies when it was just a couple of us on the plane,’ ” he told her.

So Conway encouraged Trump to go on the road and traveled with him to serve as a moderating influence. Mainly, she wanted him to “show his humanity.” She tried to get him to improve his image with women by appealing to his business sense. “You have to find new customers,” she told him. Another strategy she employed with him stemmed from the fact that Trump is such an avid cable-news viewer: “A way you can communicate with him is you go on TV to communicate,” she said. That doesn’t mean Trump took the advice. Conway said that plenty of her ideas “never saw the light of day,” adding that “we had too little time to do certain meaningful things in a consequential way, like implement a full outreach to Evangelicals, Catholics, and, of course, women.”

Not long after Conway became campaign manager, she was joined in the campaign leadership by Bannon. The two knew each other through their mutual connection to the Mercers (the family invested millions in Breitbart) and by all accounts are supportive of each other’s roles in the Trump universe. But they differ on some significant points: Conway has argued that Trump should position himself as a more traditional, limited-government conservative, according to one senior adviser, whereas Bannon wanted to use Trump to shift the whole party toward a more nationalist-populist message.

A shaggy-haired former Navy officer and Goldman Sachs banker, Bannon had, through his role at Breitbart, become a leader of the conservative movement’s new power center. From his desk in the 14th-floor war room at Trump Tower, Bannon developed a plan for Trump to go full-on Breitbart. He ratcheted up Trump’s already-paranoid speeches, casting the candidate — and his followers — as the victims of a worldwide conspiracy of the elite. “It’s a global power structure that is responsible for the economic decisions that have robbed our working class, stripped our country of its wealth, and put that money into the pockets of a handful of large corporations and political entities,” Trump told a crowd in West Palm Beach. “This is a struggle for the survival of our nation, believe me.”

Bannon, for the most part, didn’t mind Trump’s aggressive rants, crude language, and appeals to his supporters’ baser instincts. He encouraged Trump to confront his critics head-on: It was his idea to go to Mexico and Flint, Michigan. “Steve is a smashmouth guy, and so is Trump and so is Breitbart, and that’s what people want right now,” said Breitbart’s Marlow.

Ultimately, though, Bannon and Conway have struggled with Trump the same way Manafort did. On the morning of the first debate, Trump was up two points in a Bloomberg poll, but the lead evaporated after he spent the next week needlessly attacking a former Miss Universe. “It’s his campaign,” Conway said. “He’s the candidate.”

One reason Conway and Bannon have been safe from Trump’s wrath despite his poor performance in the polls: They have the trust of the Trump children, especially Ivanka and, by extension, her husband. Perhaps no one has more experience at trying to manage Trump than his eldest daughter. Ivanka, who declined to comment, has tried to temper him at various stages of the campaign, but it has proved impossible, even for her, to keep him on message. According to sources, Ivanka is especially worried that the campaign has caused lasting damage to the family business. “She thinks this is not good for the brand. She would like to distance herself from it. She’s seen some of the pressures the hotels have come under,” one adviser said. In June, Trump’s Miami-Dade golf course lost its PGA tournament to Mexico City. By October, rates had been slashed at the company’s flagship Washington, D.C., hotel, presumably because it was underbooked. And this fall, the family abandoned the Trump name when it launched a new chain of hotels.

Still, even Ivanka has been battle-hardened, to a certain degree, by this election. Before the first debate, she advised her father not to mention Bill Clinton’s accusers. “She wanted to soften him. ‘The women are not the issue, Bill Clinton is not running,’ ” an adviser said she told him. And Trump, at the time, listened. “Trump knows she’s 100 percent loyal to him, so there’s no fear of another agenda.”

But Conway told me that on the day the Access Hollywood tape leaked, Ivanka took her father’s side completely. “She was defiant,” Conway recalled. “She told him, ‘It’s 11 years old, you have to fight back. You have to say you’re sorry. But you have to fight back.’ ” Still, she and Kushner were not happy about Bannon’s plan to bring Bill Clinton’s accusers to the second presidential debate to “rattle Bill and Hillary before she took the stage.”

Another way Ivanka has tried to exert influence on the campaign is by positioning Kushner to all but run it. “You have to remember something: Jared is the final decision-maker,” a senior adviser said — except, he noted, when Trump is. Trump and his son-in-law are by all appearances close. “Jared is a brilliant young man,” Trump told me. Kushner, a lifelong Democrat, declined to comment, but a Republican close to the campaign said of his feelings: “Jared doesn’t look at supporting the campaign as taking a philosophical position. He’s opportunistic.”

In recent weeks, Kushner has served as an all-purpose fixer for the campaign. According to sources, he recruited Clinton-era CIA director James Woolsey to advise Trump on national security. Kushner’s access to Trump has caused friction with senior advisers who have chafed at his lack of experience. According to one adviser, Kushner told pollster Tony Fabrizio during the convention that the campaign didn’t need to conduct focus groups. “ ‘I can tell from the applause what’s working,’ ” Kushner said, according to this source. Kushner, through a spokesperson, denied having said this, but it is in keeping with the go-with-your-gut approach of the Trump campaign. According to the adviser, Trump rejected television ads on Benghazi and the economy that tested the best with focus groups. “I know what works,” Trump told his team. (According to a source, Trump ad-maker Rick Reed quietly withdrew from the campaign in October.)

The merits of focus groups aside, Kushner definitely likes data. He and Brad Parscale, a digital strategist who got into Trumpworld by designing websites for the Trump children, began ramping up the campaign’s data operation before the convention. A recent Bloomberg Businessweek profile of the campaign’s data team, which according to a campaign source Kushner cooperated with, portrays Kushner as a social-media innovator. “Trump knows nothing about it; this is Jared’s thing,” a senior adviser told me. “Jared was smart enough to know the key to power was money. He set the data operation up to raise money.”

Now Kushner is looking to create his own piece of the family business with a new media venture. The campaign launched a nightly newscast on Facebook called Trump Tower Live that many people see as a trial balloon for an eventual Trump TV. The broadcast has a decidedly public-access feel but adopts many of the elements of cable news: It features a panel of guests and a “crawl” of pro-Trump headlines across the bottom of the screen. Around the office, they joke that if Trump TV comes to fruition, Conway could host The Kellyanne File.

But some are skeptical of Trump TV because of the same issues that plagued Trump’s campaign: his lack of discipline and commitment. “It’s too expensive. Trump won’t put his own money in,” one prominent Republican told me. According to another Republican, Sean Hannity told conservative radio host Mark Levin he wouldn’t leave Fox to join Trump TV. (“I’ve never even discussed Trump TV with anyone,” Hannity told me.) For his part, Bannon has called the idea of Trump TV a “big, big lift,” and Breitbart’s Marlow said his boss was coming back after the election.

Trump, too, shot down the television speculation. “The last thing on my mind is doing or even thinking about Trump TV,” he told me. One reason it’s impossible to divine Trump’s media ambitions is because promoting Trump TV would effectively mean the campaign is conceding the election. “It would be a dereliction of duty to talk about it,” one senior adviser said.

One might wonder then about the campaign’s decision to publicly tout its data program — and what it might be used for after the election is over, whether that’s a media company or a political operation or some hybrid of the two. According to many close observers of the campaign, the political operatives are starting to position themselves for what comes after a loss. “It’s a window into a campaign in a downward spiral when the positioning begins,” a veteran of Mitt Romney’s 2012 run said, “but I’ve never seen it begin this early.”

In recent weeks, the mood at Trump Tower has veered between despair and denial—with a hit of resurgent glee when the news broke that the FBI was looking into more of Clinton’s emails. When I asked one senior Trump adviser to describe the scene inside, he responded: “Think of the bunker right before Hitler killed himself. Donald’s in denial. They’re all in denial.” (As Times columnist Ross Douthat put it, in a tweet, “In Trumpworld as Hitler’s Bunker terms,” the FBI investigation is “like when Goebbels thought FDR’s death would save the Nazi regime.”)

During our conversation, Trump sounded more like a guy who is happy to have finished his first marathon with zero training than the divisive presidential candidate who ignited the biggest cultural upheaval since 1968. And to hear him tell it, there’s only upside to come, win or lose. While Trump recently told a donor that he estimates the campaign diminished his net worth by $800 million, he says the effect is only temporary. “He believes he’ll have a full restoration of that inside of a year,” the donor said. “His view is the American public has a two-to-three-week attention span.” He may be right about that.

Trump is one of the most famous people alive now, and what he wants to do with that fame is unclear. Whatever it is will no doubt be as improvised as his whole campaign was. Trump says what he wants is some peace and quiet. “I can’t walk around. Not that it was easy to do before, but getting privacy back, at least a certain degree of privacy back, wouldn’t be bad,” he said. Trump told a donor at a recent fund-raiser that he planned to take a six-month vacation if he loses. “Look,” the donor told me, “he’s 70 years old. He’s going to hit the golf course or he’ll be in Scotland. He loves it there.”

But one can’t imagine that Trump, having tasted the ego fuel of tens of thousands of people chanting his name at a rally, will be able to forgo that feeling for long. He speaks of his followers fondly and is as bullish on them as he is on himself. “I think the movement stays together,” Trump told me in Pennsylvania as his motorcade sped to the airport. “Look, I just left Gettysburg, and all of the people are waving and shouting, ‘We love you, Mr. Trump.’ And I love them. There’s a movement here that’s very special. There’s never been anything like it.”

He couldn’t be more right about that.

*This article appears in the October 31, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.