Before he went into the gun business, before he started buying assault-rifle manufacturers, before he expanded into scopes and silencers, before he rolled up 18 of America’s most lethal companies into a single conglomerate, before he funded a private military base, before the massacre, before the investor revolt, before the recalls and the product defects and the bad press and the lawsuits — before any of that could happen — Stephen Feinberg, the billionaire financier, had to perfect his shooting technique. So one weekend in late 2005, he left behind the Manhattan offices of Cerberus Capital, the private-equity firm he’d founded, and his multistory Upper East Side residence, which he was in the process of spending $15 million to renovate, and traveled to Moyock, North Carolina, to the tactical-training facilities of Blackwater, the notorious private military contractor, for a weekend of long-range-firearms instruction.

Feinberg was trim, balding, blond, and wore a bristly mustache but no beard. He spoke quietly, patiently, in a gentle New York accent. Friends say he had trained in college, at Princeton, with the ROTC, parading in military drills and shooting targets with a standard service rifle, and that he had even attended jump school. But he’d left the ROTC before graduation and landed a job on Wall Street, trading securities for Drexel Burnham Lambert, the pioneer of the junk bond. Ten years later, he was running his own firm. Ten years after that, he was a Wall Street colossus.

Now Feinberg, 45, wanted to get into the field. At Blackwater, his instructor was Steve Reichert, a Marine Corps infantryman and decorated war hero who was one of the best marksmen on Earth. In Iraq, in 2004, he had shot a man from over a mile away, one of the longest confirmed hits by any American soldier in the war. Reichert had earned the Bronze Star for valor that day; two months later, he had a hole ripped in his cheek by an IED.

Having returned to Camp LeJeune in North Carolina to recuperate, Reichert started moonlighting at the Blackwater range as a shooting instructor. Feinberg, an avid elk hunter, was one of his better pupils. By the end of his second day, he was consistently hitting targets from a thousand yards away — the equivalent of 11 city blocks.

At that distance, he couldn’t just aim his weapon at the target; he had to lob the bullet like an artillery shell. “It’s not as hard as it sounds,” Reichert told me. “I could teach anyone how to do this with a properly sighted gun in five minutes.” Gravity was a constant, and one could consult a table to calculate the trajectory. What set the expert shooter apart was the ability to read the wind. “Feinberg was good at that,” Reichert said.

Cerberus manages an enormous amount of money — more than $30 billion — from several floors in a midtown office building on 52nd Street and Third Avenue. On one floor are the hedge funds, trading in distressed debt and residential mortgages. On a separate floor is the private-equity group. The latter excels at the turnaround, acquiring struggling businesses, implementing management fixes, cutting overhead, and flipping them for a profit.

Throughout the years, Cerberus has owned controlling stakes in dozens of businesses. It currently owns the Albertson’s supermarket empire and previously owned the Alamo and National car-rental chains. It has owned a water park in Texas and a television station in Salt Lake City. It has owned a school-bus manufacturer, a chain of bowling alleys, and a Japanese bank. Through one subsidiary, it ran the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Waikiki. Through another, it controlled the movie-distribution rights to The Sixth Sense. In 2004, alongside Goldman Sachs, Cerberus privatized 65,000 units of public housing in Berlin. For a time, it was the largest landlord in the city.

Behind all of this is Feinberg. He is said to be Cerberus Capital’s largest investor and reinvests most of his earnings back into his funds. His net worth is a matter of debate. Forbes magazine estimates it at $1.2 billion; office gossip at Cerberus puts it closer to $3 billion. Feinberg has said these are exaggerations.

Private equity is not a business for the patient, and once a new business is acquired, it is not unusual for Feinberg to cycle through two or three managers in search of the right leadership. His desire for quick results is masked by a constitutional equanimity: Several Cerberus insiders told me Feinberg never raises his voice, even when he is calling for someone’s head. The company’s corporate culture is Darwinian. “There was huge competition between partners,” said one former employee. “Well, not partners — just Steve Feinberg, he is the partner — but between the managing directors, it was a very ‘Eat what you kill’ mentality.”

Not long after Feinberg’s trip to Blackwater, Cerberus’s private-equity arm bought its first firearms manufacturer. The target was Bushmaster, one of the leading makers of “black guns”: highly configurable assault rifles patterned after the military-issue AR-15. Based in Windham, Maine, Bushmaster had, over the course of 30 years, grown from a tiny gun-parts manufacturer into the preferred firearm of the high-capacity target shooter. In 2002, it was the weapon of choice for John Allen Muhammad and Lee Boyd Malvo, the Beltway snipers.

Muhammad hadn’t purchased his Bushmaster legally; he’d stolen it from a gun store. But his victims were able to bring a civil lawsuit against Bushmaster, arguing that the company failed to ensure the weapon wouldn’t end up in the hands of criminals. The company was forced to settle. The payout was small — just $62,500 per victim — but the potentially unlimited liabilities from gun-injury lawsuits, accompanied by the political and public-relations hazards, had historically scared away capital and discouraged conglomeration. The industry was fragmented, consisting of numerous small, private manufacturers like Bushmaster scattered across the American Northeast. There had been Big Pharma, and Big Oil, but never Big Gun.

Cerberus set out to create it. A catalyst was the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act, pushed by NRA lobbyists and passed by a Republican-controlled Congress in 2005. PLCAA granted gunmakers broad immunity from lawsuits from victims of gun violence. A year later, Cerberus bought Bushmaster for $76 million from Richard Dyke, the company’s founder.

Dyke was a typical gun boss — a country boy, a serial entrepreneur, a lifelong Republican. He treated his workers like family members. Each month, he paid an equal share of Bushmaster’s gross profits to every employee, from the CEO to the guy who cleaned the toilets. As part of the Cerberus sale, the original Bushmaster factory would remain open for at least five years. Cerberus agreed but was a less generous manager. One of the first things it did was cancel the profit-sharing plan.

Dyke, who remained on Bushmaster’s board, sensed he was in unusual territory. “Guys like Steve Feinberg live in a different world than Dick Dyke,” he told me. “Their way of making money is very different than mine.” Dyke had held his companies for decades, earning money via dividends paid out from company profits. Feinberg earned money by charging his investors management fees. Most of these fees could be collected only once the investment had been closed — meaning that even before he entered a business, Feinberg was thinking about how to exit.

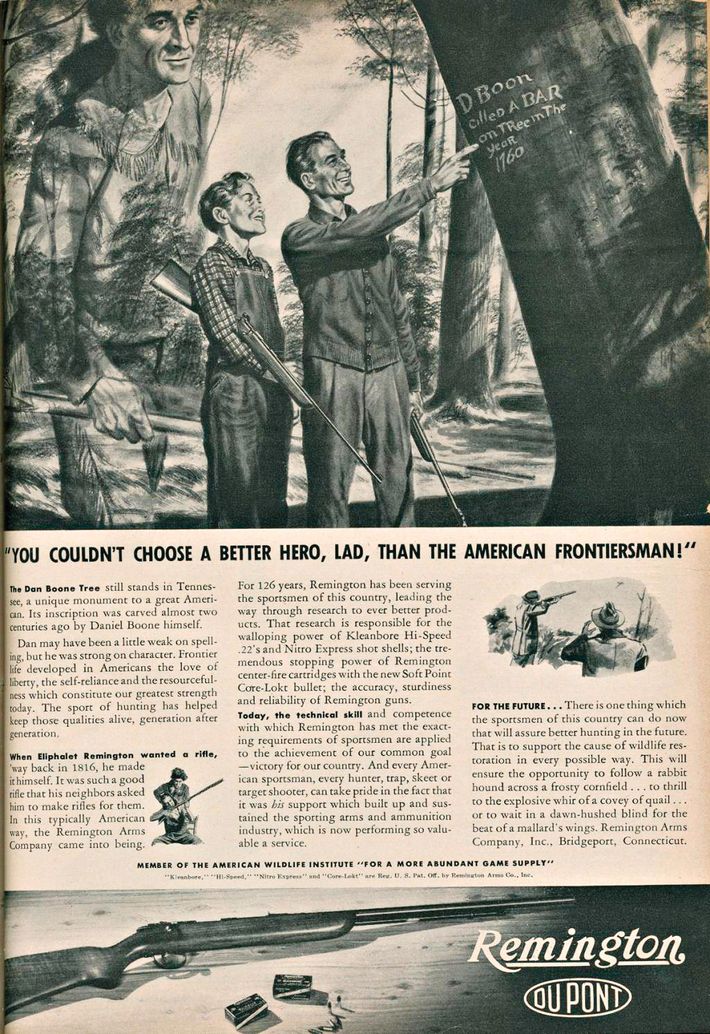

Soon after the sale, Bushmaster was folded into Freedom Group, the holding company Cerberus had chartered to conquer the gun business. Its play was obvious: roll up small gun companies, centralize management while combining costs and cutting overhead, and then, when the moment was right, sell the conglomerate to the public via an IPO. After Bushmaster, Freedom purchased Marlin, a manufacturer of lever-action hunting rifles; Parker, a manufacturer of ornate, collectible shotguns; DPMS, another assault-rifle manufacturer; and the big one, Remington, America’s oldest continuously operated gunmaker, whose .22 caliber hunting rifle had, for generations, served as the young firearms initiate’s “first gun.” Remington’s CEO, Tommy Millner, was selected to run the entire group.

Dyke was uncomfortable with the speed at which Cerberus was moving. “They were very driven to get to a billion in sales,” Dyke said. “They were driving awfully fast down the road.” After a year on the board, he quit.

Cerberus continued without him. The companies it was buying were small and inefficient, with unjustifiable overhead. Many were using equipment and methods that hadn’t been updated for decades. At Remington, some of the machinery dated back to World War II. The potential cost savings to be realized by consolidating these operations into a single, modern factory were substantial.

Freedom Group used its integrated brand portfolio as leverage. In 2008, it introduced its new Remington-branded assault rifle, the R-15. Essentially just a Bushmaster painted green, the gun was re-termed a “modern sporting rifle” and marketed to hunters. There was no disguising its military heritage, but by stamping a storied brand onto this menacing instrument, Cerberus was able to expand Freedom Group’s business in both the traditional gun-store market and the family-friendly sporting retailers. Soon, Remington-branded assault rifles were available at Walmart.

Sales of the R-15 boomed. Who was buying them? Not budding hunters, necessarily — participation rates in the outdoor sports had been stagnating for years. And, Remington brand or not, a semi-automatic assault rifle is not an appropriate choice for a first gun, or even a second. Instead, the purchasers tended to be seasoned gun collectors with large arsenals.

This demographic was key to Cerberus’s success. Surveys estimated that somewhere between 20 and 30 percent of Americans owned guns, but usually just one or two. Concentrated into a smaller demographic were the serial gun purchasers, a hard core of about 3 percent of the U.S. population. One recent survey, conducted by public-health researchers from Harvard and Northeastern universities, suggested that this 3 percent owned more than half the country’s guns. The same survey estimated that members of this demographic owned, on average, 17 different firearms.

It was easy to imagine these well-armed individuals as doomsday preppers or anti-government fanatics, but the reality, one former Cerberus insider suggested, was mundane. “Novelty sells in this business more than tactical improvements,” he told me. “The gun business is almost like a fashion business for men. You either have two or you have 20. It’s like handbags for women.”

And, like fashion, the real money was in the accessories. Freedom Group marketed its firearms not just as guns but as “shooting platforms”: modular, lethal Lego sets whose component parts could be updated for years after the initial purchase. Freedom Group regularly introduced must-have innovations — threaded triangular barrels, polarized scope filters, lightweight polymer stocks — and customers rushed to outfit their guns with the latest in firearms tech. Many of these accessories were of questionable utility. The margins on them were superb.

Freedom also benefited from broad growth in the American gun market. There are no official industry statistics for sales of new guns, but a common proxy used is the number of gun-buyer background checks conducted by the FBI each year. From 2006 to 2013, that number doubled from 10 million checks to over 21 million. Ruger and Smith & Wesson, Freedom Group’s publicly traded competitors, saw their stock prices surge.

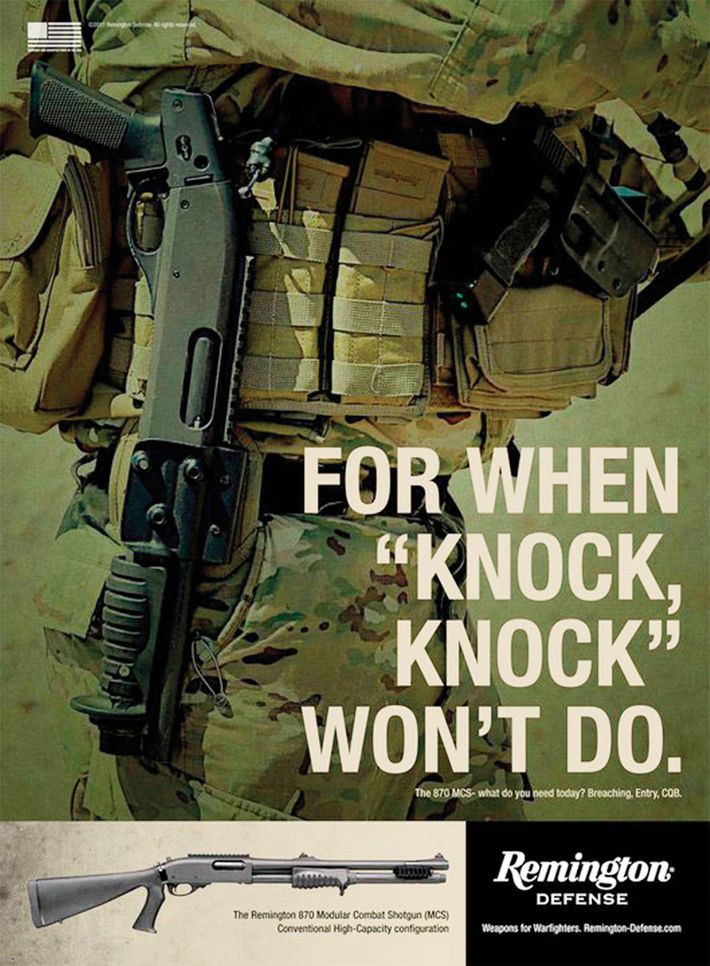

To market their shooting platforms, the Freedom Group frequently employed the cultural imagery of the global war on terror. Before being acquired by Cerberus, Bushmaster’s bare-bones product brochure had all the glamour of a catalogue of plumbing fixtures. By 2009, it looked like a recruiting poster for Delta Force.

If a Remington was a gun buyer’s first gun, a Bushmaster was the last, the ultimate fetish object for a generation acclimated to imagery from Call of Duty: Modern Warfare. Marketed to civilians as “the ultimate combat weapons system,” many of Bushmaster’s gun builds were modeled after the weapons used by America’s Special Forces. The “military-proven” guns offered the buyer vicarious status as an “operator,” although Cerberus understood well that few of its customers actually had combat experience.

“It’s impolite to call your customers ‘wannabes,’ ” said the former Cerberus insider. “So we called them ‘military enthusiasts.’ ”

Reichert saw Feinberg again sooner than expected. Feinberg’s hunting expeditions were taking him deep into the bush, outside the range of GPS, and he needed instruction in military land navigation. Reichert obliged, dragging his pupil into the swamps near the Camp LeJeune base. “We were a good 5k into an area, when my aspiring student lollygagged right into the path of one of the largest cottonmouth snakes I have seen,” Reichert wrote in an account of the trip. “I grabbed him by his collar and let the snake continue on his way.”

During the training, Feinberg was struck by the inferior quality of the camp’s range and facilities. Nearby Blackwater, he felt, had a much better setup. Reichert agreed, and the two began to discuss a new venture. Within weeks, Reichert had a business plan and had assembled a team of military trainers, including a number of special-forces veterans. Reichert named the company Tier 1 Group, after the Defense Department’s designation for its top-level commandos.

Cerberus put up the capital, purchasing a shooting range on the outskirts of Memphis for Tier 1’s facilities, a sprawling 800-acre private military base with a half-dozen shooting ranges, on-road and off-road driving courses, a parachute-drop zone, and an “urban-combat compound” designed to look like an Afghan village. Tier 1’s biggest customer was the United States Special Operations Command. Navy seals, Army Rangers, and other elite military operatives trained there in preparation for clandestine missions across the globe.

Over time, Reichert became Feinberg’s friend. He joined him on one of his elk-hunting jaunts and described the billionaire as an “ordinary, down-to-earth American.” Feinberg even offered to fly Reichert to California for a consultation with a leading plastic surgeon regarding his still-disfigured face. Reichert declined but noted that Feinberg offered to pay for medical care for a number of other injured veterans as well. His commitment to military contracting seemed to go beyond money. Tier 1 Group was profitable, but its sales maxed out at around $15 million annually — a fraction of a percent of Cerberus’s total business. Reichert sensed Feinberg was doing this out of a sense of patriotism.

“We’d get after-action reports from the front lines, saying these tactics saved us, or this medical training saved us, with details,” Reichert said. Reichert would forward these reports of Special Operations daring to Feinberg. “That made him happy.”

While Feinberg generally stayed out of Freedom Group’s day-to-day affairs, he took a personal interest in Remington Defense, the company’s military-supply wing, appointing Jason Schauble, a former Marine Corps captain, to run it. Schauble won a number of military contracts for Remington Defense and helped negotiate the purchase of Advanced Armaments Corporation, a start-up manufacturer of gun silencers. The consumer market for silencers was growing, particularly in the competitive-target-shooting community. “They’re great for urban encroachment,” said the company’s founder, Kevin Brittingham. “Silencers turn shooting more into golf.”

Advanced Armaments was small but did a lot of business with the military. “By focusing on the military market, and especially special ops, you can translate that to the commercial market,” Brittingham said. His point applied broadly: Freedom Group’s business strategy was to use America’s Special Forces as an R&D department for selling guns at Walmart. What worked in the battlefield worked in the forest. “Shooting a 180-pound deer is the same tech as shooting an 180-pound man,” said Brittingham, and Freedom was staffed with a number of people who’d done both.

This approach was duplicated across a number of other Freedom Group sidelines, including manufacturers of weapon optics, pistol grips, ammunition, even clothing. Freedom Group’s customers were buying, often at a premium, field-tested military gear. Some belonged to military families, but many were just hobbyists. Among these customers was Nancy Lanza, of Newtown, Connecticut. She purchased a Bushmaster assault rifle in March 2010, part of an expanding arsenal: three pistols, two bolt-action rifles, a shotgun, and three samurai swords.

Despite his success with Freedom Group, 2008 was a bad year for Feinberg. Cerberus held majority equity stakes in Chrysler and in General Motors’ financing division and had brought in Robert Nardelli, the former CEO of Home Depot, to run Chrysler. Echoing Reichert, Nardelli said that “Steve saw this as a huge patriotic opportunity, in addition to a great investment.” Nardelli was wrong. By 2009, both companies were in financial peril. Investors fled Cerberus.

Feinberg was saved by Obama. Although the U.S. government’s 2009 automotive-industry bailout forced Cerberus to devalue its holdings in the two firms, Cerberus was able to salvage what could have been a total loss. GMAC was converted into Ally Financial, the online bank, and Feinberg’s patriotic stake in Chrysler ended up with the Italian carmaker Fiat.

Perhaps no single person benefited more from the automotive-industry bailout than Stephen Feinberg, who, in all other respects, was a conservative. He had contributed to numerous Republican political campaigns. In 1999, he had appointed Vice-President Dan Quayle chairman of the global divisions of his firm, despite Quayle’s confessed lack of business experience. (Quayle was supposedly still respected in Asia, where Cerberus did a lot of business and where his malapropisms didn’t translate.) In 2006, he had hired George W. Bush Cabinet appointee John Snow as co-chairman shortly after the Treasury secretary resigned.

Despite these connections, Feinberg regarded himself as a regular guy. In a rare interview in early 2008, he pitched himself as a blue-collar billionaire and distanced himself from his Ivy League pedigree. “I probably would have been better off going to a state school,” he said. “I would have been more comfortable with the people.” That’s possible, but the kinds of connections you needed to persuade the Feds to bail out your bad auto-industry bet for $30 billion were more readily available to graduates of Princeton than UC-Irvine.

Freedom Group’s connection to the bailout rankled right-wing gun enthusiasts. A persistent rumor, circulated by email in 2011, alleged that Freedom Group was actually controlled by George Soros: “One of the most evil men on this planet who wants to restrict or ban all civilian guns.” The rumor was only debunked after the NRA released a statement to its members: “NRA has had contact with officials [of] Cerberus and Freedom Group for some time. The owners and investors involved are strong supporters of the Second Amendment and are avid hunters and shooters.” Two years later, three Freedom Group executives gave a million dollars each to the NRA.

While some enthusiasts collected guns, Feinberg collected gun companies. At Cerberus, he talked firearms often, once derailing a Freedom Group board meeting with a discussion of the relative ballistic merits of polymer-cased ammunition and traditional hollow-points. In 2012, his daughter Lindsey posted a picture of her father’s T-shirt to Instagram. It featured images of a sniper rifle trailing smoke, a mounted machine gun, and a row of bullets emblazoned with the tagline IT’S TIME TO WORK. In the comments, she’d posed the question: “Who is my dad…….???????”

Nardelli’s tenure at Freedom Group was disastrous. He knew little about guns; his expertise was in high-efficiency manufacturing and building economies of scale. He alienated many of Freedom’s top managers and accelerated a program of manufacturing consolidation that centralized production in Remington’s main facility in Ilion, New York. This push for efficiency meant laying off skilled workers, introducing manufacturing defects into Freedom Group products. “Since the announced closure of the North Haven factory, the quality of Marlin lever-actions has gone completely to hell,” wrote one gun blogger. “Our rifles were neither fit nor finished, nor in any condition to be offered for sale.” Gun magazines and internet forums were filled with complaints, and after Cerberus bought it, Remington was forced to issue multiple recalls, for both guns and ammunition. A number of customers sued the manufacturer, claiming their guns had gone off without the trigger being pulled, prompting a class-action lawsuit.

The gun culture’s objection to conglomeration was reminiscent of objections I’d once heard from “conscious consumers” when Unilever had purchased Ben & Jerry’s. Gun manufacturing had historically been an artisanal business, and gun buyers liked it that way. So did a former Bushmaster employee I spoke with, whose complaints about Cerberus’s conduct sounded, at times, more like complaints about capitalism itself. “I observed them screw up a lot of companies and put a lot of people out of work,” he told me. “They weren’t in it for the right reasons.” When I suggested to him that Cerberus just wanted profits, he responded with indignation. “Yeah, sure. But there’s also heritage, and history. They didn’t care about any of that.”

They certainly didn’t. When the five-year agreement to keep the original Bushmaster factory open expired in 2011, the plant was shut down almost immediately. Manufacturing was moved to Ilion, and Bushmaster customers soon noticed a drop in product quality. Within days, Dyke, the company’s founder, came out of semi-retirement at the age of 77, reopening his old factory under the new name Windham Weaponry and hiring back nearly all of the original employees. Selling a gun that was an original Bushmaster in all but name, the new company grew to $65 million in sales in less than five years. “There’s no doubt we’re taking customers away from the old Bushmaster base,” Dyke said.

By March 2012, Nardelli was gone. He was replaced by another Cerberus insider, George Kollitides, who oversaw a plan to relocate most of Freedom Group’s manufacturing to a disused Chrysler facility in Huntsville, Alabama. The move offered nearly $40 million in state tax incentives, but Freedom Group still struggled. As 2012 came to a close, Cerberus’s gun play was nearly seven years old — ripe enough for an exit. Investment managers weren’t likely to view the company favorably until the company’s product-quality concerns were addressed. Kollitides needed a fix, quickly.

Fortunately — for him, at least — there was one thing that always, infallibly, drove gun sales through the ceiling: a mass shooting.

When Adam Lanza shot his mother, Nancy, in her sleep on the morning of December 14, 2012, he used one of her bolt-action rifles, a Savage Mark II. He then discarded this gun and prepared for a tactical assault, arming himself with two pistols, a shotgun, and her Bushmaster assault rifle, along with ten 30-round magazines. Using a technique employed by Special Forces operators, he then taped these magazines together into bundles of three, allowing for immediate reload. Then he went to Sandy Hook Elementary School and shot his way into the school, killing six adults and 20 schoolchildren, all with the Bushmaster, in less than ten minutes. Then he shot himself in the head.

During the flood of grief that followed, an outcry erupted directed at Cerberus, Remington, and Bushmaster. By some karmic coincidence, Martin Feinberg, Stephen’s father, lived in Newtown, in a senior community. It was rumored that, following the massacre, he asked his son to sell the company. He was joined in this request by the California State Teachers’ Retirement System, a key Cerberus investor and one of the largest pension funds in the country, which threatened to pull its money from the firm if it didn’t divest from its gun investments. Cerberus issued a statement, promising it would move to sell Freedom Group immediately. Of course, it had wanted to do that all along.

Feinberg wanted over a billion dollars, but he couldn’t find a taker at that price. The original idea, of an IPO, was out of the question: No reputable investment bank would underwrite it, nor even take the M&A fees associated with a private deal. Another option would have been to sell off the most controversial product lines, like Bushmaster, but the centralization of manufacturing made that impossible, too.

But the fear of regulation in the aftermath spurred gun hoarding, and this was good for Cerberus. In late 2013, Freedom Group rebranded, changing its name to Remington Outdoor Company. By the end of the year, Remington Outdoor’s annual sales had finally passed its billion-dollar target. It was its most profitable year.

The boom was short-lived: The 2014 rollout of a new pistol, the Remington R51, was a disaster — an unreliable shooter with serious production flaws, the R51 was the Galaxy Note of the firearms industry, and Remington ended up recalling the guns. Having once sought a billion dollars for its investment, Freedom was, according to insiders, now internally valued at just $400 million.

The next year was even worse. In 2015, Walmart announced it would no longer carry assault rifles. That same year, Remington’s annual sales fell almost 35 percent from its post-Newtown peak, even as Remington’s public competitors outperformed. The lawsuit over the faulty Remington trigger mechanism had forced the company to offer another recall, this time for more than 7.5 million units, and the firm ended up losing more than $135 million in a single year, for a net profit margin of minus 17 percent.

Meanwhile, with elementary schools across the country now forced to conduct “active shooter” drills, the California teachers were demanding out. Unable to find a buyer, Feinberg proposed a deal: He’d pay a special onetime dividend from Remington Outdoor’s accrued earnings, letting investors cash out, and Remington would be placed in a special-purpose vehicle, concentrating ownership of what remained in the hands of a few die-hard Cerberus insiders. Of course, “owning” was a questionable term here; by the end of 2015, Remington Outdoor Company was worth less than the debt attached to it, like a house with an underwater mortgage. In June of this year, the company’s latest CEO, Jim Marcotuli, stated the obvious: “We’re not for sale.”

Several people I spoke to said Cerberus had extracted enough cash from Remington during the good years to meet the firm’s threshold rate of return, and so, in a narrow sense, the investment was a victory. But the social fallout had cost it dearly, affecting its ongoing access to capital in a way it hadn’t foreseen. Owning a gun business doesn’t just affect one’s reputation — it also affects one’s ability to own other, less controversial businesses. Profits or not, other private-equity firms, having witnessed an unprecedented revolt from investors, won’t touch it. It’s the investing equivalent of toxic waste.

For now, that waste is buried in Steve Feinberg’s yard. As the head of Cerberus, he personally owns a controlling, concentrated stake in the firm — likely a majority. Internally, business conditions are improving, as Marcotuli’s cost-cutting fixes have returned the company to profitability. But revenue remains soft in a market still saturated by the assault-rifle-buying frenzy of 2013, and Remington, in a tacit acknowledgment of its critics, has abandoned the kind of combat-oriented marketing imagery that so excited its customers.

That marketing was the focus of the lawsuit brought against Remington by the victims of Sandy Hook. Although the PLCAA granted immunity from lawsuits of this type, lawmakers had left an exception: “negligent entrustment.” This term referred to the rights of victims to sue gun dealers who had sold weapons irresponsibly — say, to a customer who was obviously drunk or homicidal.

The attorneys for the victims’ families argued that Freedom Group’s marketing, with its aggressive slogans and its fetishistic imagery of SWAT teams and Special Forces operators, was a large-scale example of negligent entrustment and that Remington had cultivated a dangerous and uncontrollable demographic with predictable results. The courts didn’t buy the argument, and last month, the judge in the case dismissed the lawsuit. It was the closest victims of gun violence had come since PLCAA’s passing to holding a gun company responsible, but in the end, Cerberus’s bet that the law would shield its investment turned out to be right.

Reichert, the shooting instructor, eventually left Tier 1 Group to work on a classified high-tech firearms program for DARPA. He remained on good terms with Feinberg and had only positive things to say about his experience with Cerberus, but he conceded that the firearms side of the business had been a disaster. “I know all the guys involved,” he said. “In the end, none of them were happy they sold.”

Reichert remained an outspoken advocate for the broadest possible interpretation of the Second Amendment. So, too, did every other gun-industry executive I spoke with. None of them wavered in the slightest, not even when I brought up the Newtown massacre, or the Pulse-nightclub shooting, or the San Bernardino attacks, or the shooting of the Dallas police officers, or the certainty of other massacres to come. The exception was Richard Dyke, who conceded a single point. “Look, I grew up in rural America,” he said. “But if I lived in New York City in a building with a hundred people, and I saw a guy with an assault weapon in his hand in the hallway, I think I’d go back in my apartment.”

Feinberg actually did live in New York, but he didn’t waver either. In early 2016, Donald Trump unexpectedly decapitated the Republican Party, and GOP power brokers were forced to choose sides. Feinberg picked Trump.

The two were both pseudo-populist billionaires from New York, but otherwise dissimilar. Feinberg downplayed his wealth; Trump exaggerated his. One of the keys to Feinberg’s success was his focus; Trump had the attention span of a mayfly. Feinberg shunned the press; Trump sought publicity wherever it was to be found. But Feinberg was able to overlook these character flaws, and — somehow — the frothing anti-Semitism of the Trumpist fringe as well. At Trump’s fund-raising dinner at Le Cirque in June, he made the largest political contribution of his life: more than $678,800, split between him and his wife. The donation made him one of the top contributors to the Trump Victory fund and earned him a spot as one of the 13 business leaders on the Trump Economic Advisory Council.

Trump’s victory means Feinberg will ascend to a position of influence he has never experienced before. It also probably means a paradoxical slackening of demand in the gun market, further devaluing Feinberg’s investment. Without the fear of a Democratic president seizing their guns, there’s no need for hoarding. But for Feinberg, that’s a small price to pay.

*This article appears in the November 14, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.