The city was always an asylum. On television on Election Night, the word they used was bubble. But what a bubble.

New Yorkers woke up on November 8 in what seems now like a fairy-tale fog, convinced, as ever, that the future belonged to us. By midnight, the world looked very different, the country very far away (and the future, too). Eighty percent of us had voted against the man who won, and 80 percent, it seemed, were already hatching plans to leave — for Canada or Berlin or anywhere else we imagined we could live safely among the like-minded. That was when the text messages began coming in from old friends in Wisconsin and Texas and North Carolina and Missouri. They were watching the same returns we were, in the same apocalyptic panic, and all making desperate plans to come to New York. For them, the city was still the same fairy tale.

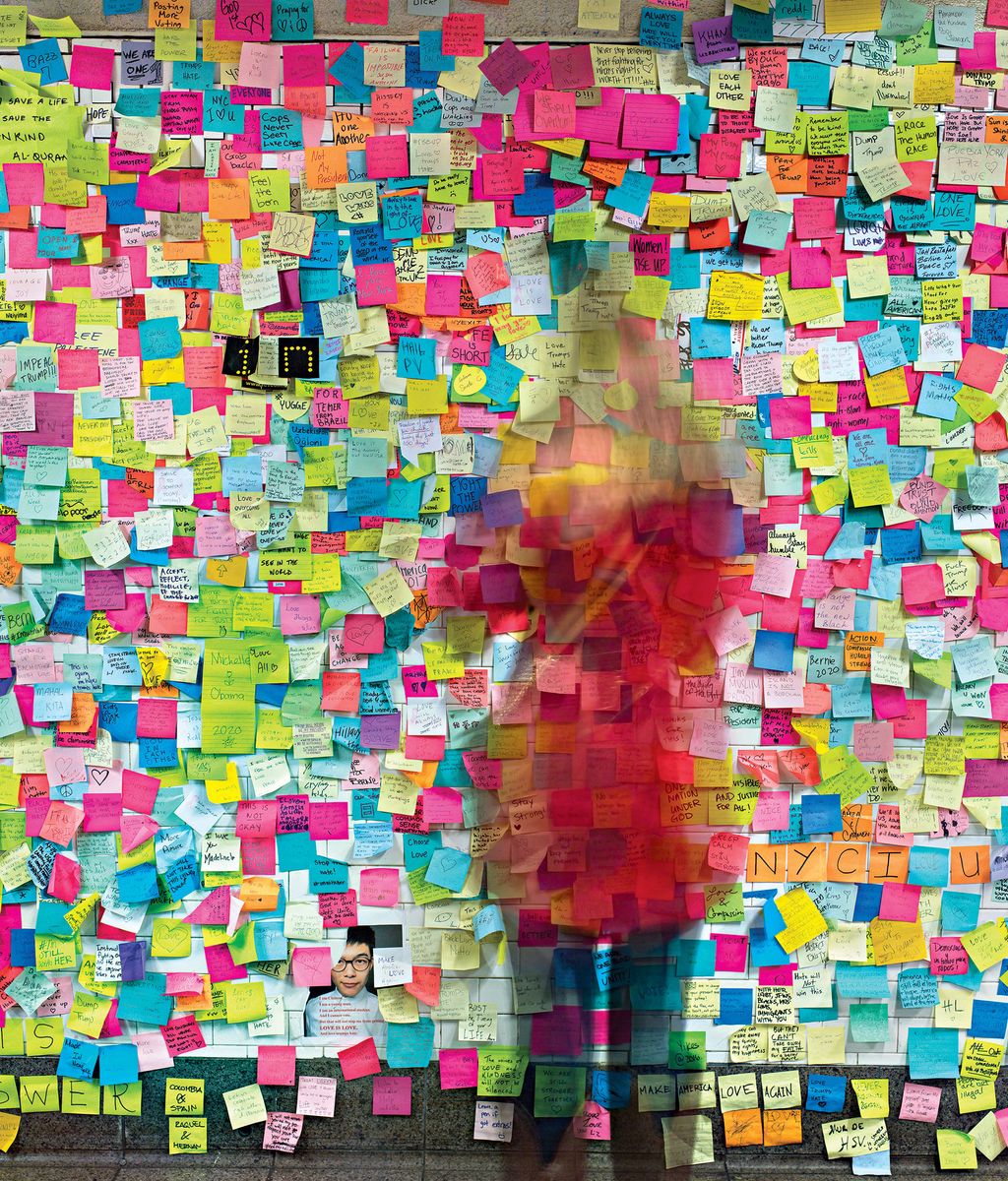

And for us, those 80 percent in denial and despair, the city itself was a consolation. The human traffic on the streets that next morning was funereal, but it did proceed, commuters stuffed shoulder-to-shoulder on subway cars, crying. More amazing, here: They were looking each other in the eye as they bawled. There were hugs among strangers, and many more bleary-eyed nods, on streets that seemed dusted with ash. It was a bubble, of course, but after the election, the city unbubbled us too — popped us out of our blister packs of despair. An endless campaign that had unfolded mostly in the privacy of our screens was mourned outside, communally, socially. Street life was a comforting orgy, and the smallest things turned into talismans — the MetroCard, the fruit stand. It was easy to imagine the world ending when the world was a relentless cascade of panicked tweets. It became a lot harder, actually, once you stepped out your front door.

The news was full of hate — beginning that morning, with students marching through hallways chanting about white power. The city had flare-ups, too, but when swastikas showed up in Adam Yauch Park, of all places, the graffiti was plastered over with hearts. Apartments turned into little crèches: sisters coming together for quick comfort and staying over for three days; black families shaking their heads and rolling their eyes at the disbelief of their white friends. A stern male co-worker of mine made a beeline for a younger female colleague and repeated the words he’d told his daughter that morning: “It’s always been this way, it always will be, and I’m so, so sorry.” A West Indian immigrant asked three strangers he’d just met how he should have answered when his 8-year-old came to him, the next morning, saying plaintively, “I thought we weren’t supposed to bully.”

Life went on. There were babies born that day in our hospitals, half of them girls, to mothers who thought their daughters’ first memories might star a female president. There were boys born named Barack. The market rallied. Pedestrians yelled at truckers for their bumper stickers, and the drivers yelled back, and that was kind of great, too. We’d almost forgotten where Donald Trump came from.

The city was always an asylum. But what kind — a sanctuary or madhouse?

It was both, the tumult being the price of admission — and in certain ways the enticement, too. New York is no utopia, no Portland; it has never sung in harmony. One consequence of real diversity is real conflict, and so our cosmopolitanism has always had two faces. With all due respect, America, that’s what makes it real.

Before Eric Garner and before the ground-zero mosque, before Rudy Giuliani called Chris Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary “sick stuff” and before Trump called for the execution of the Central Park Five; before Abner Louima and before stop-and-frisk and before the Crown Heights riots; before Stonewall began with a police raid; before redlining; before the 1927 Klan riot, when Fred Trump was arrested wearing white; before 38 were killed by a 1920 bomb detonated by anarchists outside J. P. Morgan; before 120 died, mostly free black men, mostly at the hands of Irish New Yorkers raging through the city, resisting enlistment in Lincoln’s war to free their brothers; before all that, when Peter Minuit of New Amsterdam legend established the city as a sanctuary for mercenary commerce on a seaboard being settled, in every other colony, by religious ideologues, it was not by war or raid or smallpox but merely by submitting an exploitatively low bid. Those 24 dollars were consecrated into acquisitive legend almost immediately — a fabulous deal, a terrific deal, and also, sort of, a con. It set a template New Yorkers would emulate for centuries, as the city’s big-tent open-mindedness covered something darker: violence of certain groups against others, neighbors exploiting neighbors for the prize of living among one another and maybe even conquering the world. This makes for a very particular kind of tolerance. We tolerate living around bad guys doing bad things, in part because we can always tell them to fuck off. And often do.

Millions of dreamer-hustlers came anyway — from 1892 to 1954, 12 million through Ellis Island alone. Elsewhere in the country, new arrivals had set up shop and claimed primacy where they landed. Here, newer waves just kept coming, swamping the claims of those who came before, wave after wave, Irish and Germans followed by Russian Jews and Armenians and Poles and Czechs and Slovaks and Greeks, tidal waves leveling into ethnic palimpsests of communities so enormous and elaborate they might have been called whole civilizations just 500 years before (Kleindeutschland, the Five Points, Central Park’s black Seneca Village). When the country closed its borders in the spirit of “racial hygiene,” the immigrants were followed by American freaks, fleeing suburbs and parents and finding refuge here.

Native-born New Yorkers can seem precocious marvels to newcomers, but they rarely hold the city’s gaze for very long — ask Andy Warhol (from Pittsburgh) or Madonna (Detroit), Zora Neale Hurston (from Notasulga, Alabama) or Langston Hughes (Joplin, Missouri), Truman Capote (New Orleans) or Dorothy Parker (Long Branch, New Jersey), or even Andrew Carnegie (Scotland) and J. P. Morgan himself (Hartford, Connecticut). Nobody knows any Dutch, which meant nobody has really come first, when you think about it, which means nobody really owns the city, even the obscenely rich who talk like they do. The city is so much a hot spring of immigrants and migrants and arrivistes, self-inventors and refuge-seekers and self-mythologizers, that no one can ever feel quite comfortable or secure, no matter how royally statused. The churn is eternal and the envy general, like antibodies to complacency. No one is immune to insecurity, not the sons of tycoons or the daughters of mayors or the offspring of artists and musicians raised as downtown royalty on lower Fifth Avenue. Not even the golden-haired boy born into a real-estate fortune in the glorious sun of the white man’s mid-century boom who built a gold-plated empire for himself out of the resentment he felt staring out across the East River at Manhattan from Queens. And who wanted, even more than to conquer the Manhattan skyline, to watch his own tabloid fantasy become “real” in the pages of the New York Post. BEST SEX I’VE EVER HAD is surely, even now, the greatest day of the president-elect’s entire life.

New York made Donald Trump, and, to spite us — to spite the expectation that wealthy New Yorkers will repay the opportunities of city life with cosmopolitanism and taste — he made himself king.

For many New Yorkers, Election Night felt like the end of their empire. But of course the election was also a New York coronation. The senator from New York lost, just as the democratic socialist from Brooklyn had before her. But the boy from Queens won. And he is taking with him into his black-gold court fortress the former mayor, from Flatbush; his own children and one of their husbands, himself the son of a master builder; and what seems, at times, like half of Goldman Sachs. What might have hurt the most was that the country had finally elected a New Yorker, the first since FDR, but one who represents the id we tried most of the time to suppress. We thought of ourselves as beacons of enlightenment and icons of the technocratic liberalism that would surely rule the 21st century. But the country had picked, from among all our many plutocrats vying to puppet-master the world forward, a know-nothing. The irony was, so taken by surprise, we felt, for a night anyway, we knew nothing too.

But we knew one another. Urbanism isn’t perfect, certainly not as we’ve ever managed to live it in New York. It’s brought us income inequality and political complacency and an ugly disdain for the forsaken voters on whose rage our boy-king just boogie-boarded into office. But the city is not one that will respond to that comeuppance with humility. And as the days wore on after the election, and we settled back into our know-it-all selves, we began to feel a little less ignorant or even ill-informed. We know plenty. We know tolerance and science and that cosmopolitanism does not mean unanimity but that it does mean vitality, and that you shouldn’t intervene when two drug addicts are yelling at each other outside a Chinatown subway station but that you should when it’s one of them yelling at a Mexican woman to clear out of town. We know that, whatever he thinks of Hamilton, there are safe spaces for the president-elect in this city — Staten Island, for starters, and Hasidic Williamsburg and the ‘21’ Club and Jean-Georges, apparently. Thankfully, we know there are unsafe spaces, too, including right outside his front door, where many continue to rally every day despite the armored trucks and sandbags and police with blacked-out name tags. We know that “inner cities” aren’t “war zones” and that ending discriminatory policing doesn’t lead to a rise in gun deaths — we actually know that because the city is an urban laboratory for city-first governance, and it has yielded real results. We know that putting America First means welcoming the world, and we know our immigrants have enriched us, not raped us. We know that city life can be ugly, but also that we are all strong enough to live among some ugliness. We know that, stranded in a country that may soon privatize public schools, we have just established universal pre-K, and we know — or think we know — that it works. We know that we have pretty gender-accommodating public bathrooms because we know people who still fuck and do drugs in them. We know that La Guardia is a dump — but so what? We know this city is, ultimately, ungovernable — that it’s too unruly, that it’s at its best when it’s unruly, and that its unruliness is what gave rise to what people like Trump used to call the American Dream. We know that people like him are the cost of that unruliness, and that you can learn to live with them by mocking them. We thought we knew the country would listen to our warnings, but we’re not going to stop making them. We know, whatever one might think of Bill de Blasio, our giant in Gracie Mansion is up to the task of grandstanding, suggesting he’d erase the city’s ID-card data rather than endanger immigrants. We know the city will be independent, and we know the city will also continue to be itself — a theater of freaks and refugees and the restless who were never elsewhere able to feel at home. We know that an open and tolerant and progress-minded future still lies before us, even if we have to go it alone, and even if that future now looks a few feet smaller at the shoreline.

And we also know that we are not in fact alone — that New York is not an island but an archipelago. Our mayor has resister-cousins in Chicago and Los Angeles and Providence, San Francisco and Seattle and Minneapolis — and those are just a few of the cities mobilizing themselves as immigrant sanctuaries. We know that the number of Democratic counties has shrunk over the last decade or two, as entrepreneurs and other hustlers flooded into cities, and we know that the counties that went blue in this election account for nearly two-thirds of the American economy. We also know that Peter Thiel was basically the only Trumper in Silicon Valley. If you have to live in a bubble, really, you could do worse.

On November 8, I’d woken up and padded downstairs in my slippers to the lobby, where voting booths appear every Election Day — a legacy of disgraced Albany strongman Sheldon Silver, I’d always thought, whose political base was in the brick high-rise garment-worker co-ops, built after the war, that had converted this strip of Grand Street from tenement Lower East Side to almost-middle-class-ness. I stood there, in line, with my wife, whose parents had grown up in these buildings with Silver himself. They got together at 16. The daughter of a postman whose own father had come here from Sicily (via a ship from Palermo after a week on a donkey) and a seamstress turned Coast Guard secretary raised by a single mother of ten after her felon of a father abandoned their family for one of his other two; and the son of a clotheshorse housewife born “uptown” in a tenement on East 10th Street and a milliner who had lived on his own since the age of 7, when his mother died in the influenza epidemic and his father’s new wife threw him out and he started sleeping in a rotation of stairwells in the tenements of his friends — which is where, as a teenager, he met his wife. By the time the urchin had a family, he also owned a hat factory and was called, around the neighborhood, a gentleman. Their son, who sold pot to his friends in the building and was once arrested out of class at Stuyvesant after a knife fight, became a corporate lawyer and eventually general counsel of an investment bank, based in the clouds at the top of the World Trade Center, that lost 658 employees on September 11. You could write a novel. When I first came to meet the extended family, dozens gathered outside on Grand for a funeral procession one summer morning, I was the only one there who hadn’t grown up within a single block of where we were standing — or where I was standing now, as I waited for Risa to vote. When she came out of the booth, in that lobby, she was covered in tears.

It was a hard night. I don’t think I slept, just cried through the early-morning hours with my eyes closed. I got up around dawn and wandered into the living room and toward the window, where Risa keeps a set of binoculars for spying on our neighbors. At first, I’d been horrified. “What, you think I’m going to be the one shmegegge in the co-ops without them?” she said, laughing. “But what will you say if someone sees you looking at them?” She laughed again. “I’ll say, ‘Welcome to New York.’ ”

To the east, the early-morning sun was gleaming off the river under the bridges, and a single taxicab, for hire, turned around the corner of Cherry Street toward the projects where her grandfather had been raised. It felt like a miracle, to see the world moving again — to see it for hire again. I picked up the binoculars. Across the way, to the right of the window, where a crew of Hispanic construction workers spent days watching television in an otherwise unfurnished space, and below the window of the German friend who spotted us smoking joints after we had bailed on her Fourth of July party, saying we were out of town, and above the courtyard where the building’s Orthodox Jews built their sukkot and ate their suppers together every October — someone had hung an American flag. I was crying again. I didn’t know which America it was celebrating: Trump’s or the new resistance’s. But it didn’t matter. Either way, it was ours.

*This article appears in the December 12, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.

*The original version of this article included the story of a Baruch student in a hijab harassed on the 6 train, a story that police say she recanted after we published.