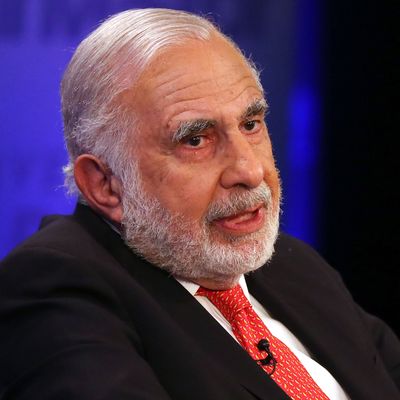

There is no one inside the Trump administration — and not many people, period — richer than Carl Icahn, the 80-year-old financier who last month was named special adviser to the president on regulatory reform. With a net worth of $18 billion, he has more money than all the other billionaires on Trump’s team put together. And in a transition marked by what seems to be a flagrant disregard for the appearance of conflicts of interest, Icahn also arguably belongs atop the list of Trump officials best situated for self-enrichment. Trump has tapped Icahn to “reform” the very agencies that are overseeing his investments, which are concentrated in sectors like energy, auto supplies, and mining. So far, that work includes helping to choose the heads of the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Environmental Protection Administration, as well as telling them which regulations need changing.

Like Trump, Icahn has not announced any plans to sell his businesses to avoid conflicts of interest that might arise from his work for the administration. He apparently won’t file tax returns or go through any sort of congressional vetting. In short, he’s an unaccountable figure with great influence who at the very least seems philosophically committed to cutting regulations that will allow his own businesses to become more profitable — likely with significant environmental and market effects for the public. Icahn is already pressuring the FTC to roll back regulations on clean fuel. He could also push the SEC or the Federal Trade Commission to go easy on companies in which he has a stake, regarding pending mergers or other issues. He could even pressure the SEC to make it easier for players like him to take big stakes in companies without informing other market participants.

The lack of any accountability is premised on the fact that Trump isn’t formally hiring Icahn. “It is one more example of what King Trump is doing, circumventing the rules,” Richard Painter, the former chief ethics counsel to President George W. Bush, told New York. Painter, who has been critical of the Trump family’s business conflicts, said it is “unprecedented” for a special adviser to the president to not be a government employee, even if he is not being paid and working only part-time, as is the case for Icahn. If he were called an employee, Icahn would have to sell his interests in any and all companies substantially affected by the regulations he’s in charge of overhauling or be in violation of the law, according to the ethics expert. Icahn could also be required to file financial disclosures and wouldn’t be allowed to trade on any inside information he might receive from the government as a result of his work. “This is an end-run around criminal statutes,” said Painter.

As wealthy as Icahn is, it’s been a tough few years for him. Billed as a corporate raider in the 1980s and in this century recast in the slightly more genteel role of shareholder activist, Icahn runs an internal hedge fund that, by the end of September, had lost a third of its value since 2014, in large part owing to Icahn’s many soured energy bets. Icahn Enterprises is also hurting. Prior to the election, shares in the deeply indebted, junk-rated holding company had declined by almost two-thirds since peaking in December 2013. This summer, a UBS analyst said that Icahn Enterprises, which houses a dozen companies Icahn owns or controls, was substantially overvalued — trading at what critics estimated to be almost double its net asset value. The portfolio includes casinos, mines, refineries, and auto-related companies. Part of the Icahn Enterprises business model is to squeeze these companies to pay huge dividends to the parent, even when they are struggling.

As a result of his troubled portfolio, Icahn’s personal wealth had fallen by almost $10 billion before the election, from a peak of $24.5 billion (as estimated by Forbes) in early 2014. Now he’s on the rebound, profiting handsomely from Trump. Shares of Icahn Enterprises have jumped more than 25 percent since the election, 8 percent of it on the announcement of his new job. His worst performer is CVR Energy, a refinery that has been pummeled by EPA rules designed to promote renewable fuel. It gained about 20 percent since Scott Pruitt, the Oklahoma attorney general who has sued the EPA several times, was named to head the agency, after Icahn vetted him.

In an interview with Bloomberg, Icahn said he spoke to Pruitt “four or five times” before Trump tapped Pruitt to run the EPA. When it comes to EPA regulation, Icahn is particularly incensed about something he referred to in a recent interview as this “goddamn RIN law.” Refinery owners, including Icahn, have railed against RINs, or Renewable Identification Numbers, for years. RINs are tradable credits that refiners must buy to prove they have met the EPA’s renewable-energy standards by blending their gasoline with plant-based fuels like ethanol, which is often done by gas stations, not the refiners themselves.

Icahn and other refinery owners claim the rising price of RINs could put them out of business. Icahn owns 82 percent of CVR Energy, which has refineries in Oklahoma and Kansas.

As Oklahoma’s attorney general, Pruitt also criticized the EPA-run program that created the market for RINs. Icahn told Bloomberg, “I’ve spoken to [Pruitt], and I do think he feels pretty strongly about the absurdity of these obligations,” referring to the rules mandating that refiners buy RINs.

Painter points out that all of this would be illegal if Icahn were officially a government employee. “It would be a crime to participate in any conversations that have a direct impact on his financial holdings,” said Painter. “If in the course of interviewing someone for that job, he starts bringing that topic up and pushing for that regulation to be rescinded, at that point, that’s a criminal offense if he’s an employee.”

Icahn general counsel Jesse Lynn told New York that the mogul “is well aware of his obligations under the law generally and with respect to 18 U.S.C. § 208” — the criminal conflict-of-interest statute prohibiting an executive-branch employee from participating personally and substantially in a government matter that will affect his own financial interests — “and he will follow the law as he always has.” Icahn will not do anything to “trigger” his status as a “special government employee” either, he said. Such employees are officers or employees who are retained, designated, appointed, or employed to perform temporary duties, with or without compensation, for not more than 130 days during any period of 365 consecutive days.

Icahn also vetted candidates to oversee the SEC, which is investigating at least five companies in which he owns significant stakes. The SEC this year confirmed ongoing enforcement probes of Herbalife, Hertz, and Navistar, according to Probes Reporter, which tracks such investigations via FOIA requests. CVR Energy and Freeport McMoran, two other Icahn holdings, are also under investigation by the SEC, said Probes Reporter CEO John Gavin. On Wednesday, Trump said he plans to nominate Wall Street lawyer Jay Clayton as SEC chairman.

As Painter puts it, letting Icahn choose the SEC chair “is like letting one of the teams in the game pick the umpire. It’s flat-out wrong.” Regardless of Icahn’s official status, Painter thinks the investor should be selling his investments.

The FTC is another agency whose actions directly affect Icahn’s pocketbook, but whose regulatory scheme he could nonetheless be reviewing. The FTC battled Icahn-controlled Herbalife for years before reaching a $200 million settlement, which requires the company to be overseen by an independent monitor for seven years. But critics worry that an Icahn-friendly FTC won’t do anything to Herbalife if it breaks the terms of the deal, which prohibits payments for recruitment, the hallmark of a pyramid scheme.

The FTC under Republicans long had a hands-off attitude toward multi-level marketers like Herbalife, notes Bill Keep, dean of the School of Business at The College of New Jersey and a prominent MLM critic. He fears that happening again. “My concern is that the FTC will revert back to their 2011 stated position which was that any additional reporting from the MLM industry would outweigh the costs,” he said, noting that the FTC came to the opposite conclusion with Herbalife and promised to apply its new standard industry-wide.

Another of Icahn’s companies, American Railcar Industries, is already suing its regulator, the Federal Railroad Administration, which found that its tank cars were leaking and ordered that hundreds of them be tested. Soon, this will not be Icahn’s problem anymore: Last month he agreed to sell American Railcar to a Japanese bank for about $3.4 billion.

“I am proud to serve President-elect Trump as a special advisor on regulatory reform,” Icahn said in the statement announcing his new role. “Under President Obama, America’s business owners have been crippled by over $1 trillion in new regulations and over 750 billion hours dealing with paperwork. It’s time to break free of excessive regulation and let our entrepreneurs do what they do best: create jobs and support communities. President-elect Trump is serious about helping American families, and regulatory reform will be a critical component of making America work again.”

In a CNBC interview the day after the announcement, Icahn tried to preempt any potential questions about conflicts. “It’s almost as ridiculous as saying, you know, Donald shouldn’t talk to a Jamie Dimon or Brian Moynihan about bank regulation because they are CEO of a bank,” he said, referring to the CEOs of JPMorgan and Bank of America. “It’s sort of a crazy issue.”

“To suggest that there is something nefarious about him offering his opinions on regulations affecting the refining industry just because a portion of his large and diversified investment portfolio happens to be in that sector is … ludicrous,” Icahn’s general counsel Lynn told New York.

Jason Miller, the transition team’s former communications director, who stepped down over Christmas weekend in the midst of an apparent sex scandal, said the administration will take steps to address any Icahn’s conflicts. “Obviously, there are proper oversights and there will be plenty of transparency when it comes to how this all ultimately comes together,” he told reporters in a media briefing following the announcement.

Icahn was the first, and for a long time only, major Wall Streeter to back Trump, who suggested Icahn should be his Treasury secretary shortly after launching his campaign. “Carl was with me from the beginning and with his being one of the world’s great businessmen, that was something I truly appreciated,” said President-elect Trump in a statement announcing Icahn’s new role. “His help on the strangling regulations that our country is faced with will be invaluable.”

Icahn said early on that he didn’t want the Treasury job. Now he’s accepted a role in the Trump administration that promises to be much more lucrative.