In his inaugural address, President Trump vowed that “the forgotten men and women of our country will be forgotten no longer.” He then suggested that the government has a responsibility to provide its “righteous people” with “great schools for their children, safe neighborhoods for their families, and good jobs for themselves.”

The hedge-fund billionaire who bankrolled Trump’s campaign takes a different view. Robert Mercer reportedly believes that “human beings have no inherent value other than how much money they make,” and that “society is upside down” because “government helps the weak people get strong, and makes the strong people weak by taking their money away, through taxes.”

Thus far, Trump’s governing style has been more in keeping with his donor’s private views than with his own official ones. The president has backed a health-care plan that finances a tax cut for millionaires by throwing millions of “forgotten” Americans off of Medicaid — while proposing a budget that would slash spending on public housing, food assistance, after-school programs, and development funds for poor rural and urban areas.

These actions represent the “normal” part of the Trump presidency. The fact that the new Republican president is serving as a loyal general in the one percent’s class war would be wholly unremarkable, had Trump not campaigned as a populist outsider. But then, if Trump hadn’t run as a populist outsider, it’s quite possible that there wouldn’t be a new Republican president. The mogul’s success in the primary and general elections had many causes, but one was likely his avoidance of conservative platitudes about bootstraps and “makers and takers.”

Typically, Republicans attribute the despair of impoverished communities to the moral failings of individual poor people. But Trump never lamented the “culture of poverty.” Instead, he blamed the misery of the “forgotten” on rapacious elites who had failed to protect the “righteous” people’s economic interests.

This message — when liberally (or, perhaps illiberally) salted with appeals to white racial resentment — proved to be a winning one. In a country that saw its economic elite engineer a financial crisis — and then reap the lion’s share of the gains once growth resumed — the market for paeans to job creators has contracted sharply. This is true even within the Republican Party, which has grown increasingly reliant on the support of downwardly mobile white voters.

Trump wasn’t the only Republican to recognize that his party’s “we built that” shtick had fallen out of fashion. Paul Ryan took back his whole “makers and takers” spiel in March of 2016. And during their years-long assault on Obamacare, Republicans mostly attacked the law from the left: Instead of arguing against the morality of taxing the wealthy to expand Medicaid, many conservatives lamented that Obamacare had left too many Americans with insurance they can’t afford to use.

Trump gave the GOP the rebrand it desperately needed. But, thus far, he’s made few alterations to the actual product. And, judging by their failed attempt to pass a supply-side tax cut dressed as a health-care bill, Republicans believe that the only thing their agenda ever lacked was a racist reality star as its salesman.

But they are wrong about that: Movement conservatism is failing politically because its policies have never had less to offer the voters it relies on.

New research on the surging death rate among white, non-college-educated Americans offers a harrowing testament to this fact. In 2015, Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton discovered that an epidemic of suicides and substance abuse was driving up the mortality rate of middle-aged, working-class, white Americans — even as medical advances were pushing down that rate for college-educated whites and every other racial and ethnic group.

Last week, Case and Deaton published a new paper exploring the causes of this development. It identifies a number of accessories to the crime: Stalled progress on the prevention of heart disease and climbing rates of obesity and diabetes contributed to their morbid finding.

But the prime culprit in their story is the collapsing social mobility and living standards of working-class Americans.

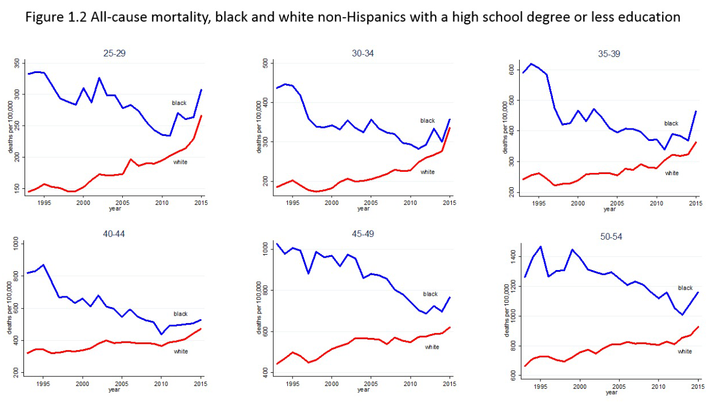

Since the great recession, black and white non-college-educated workers have seen their mortality rates rise, across every age group. And working-class African-Americans still suffer higher death rates than white ones do.

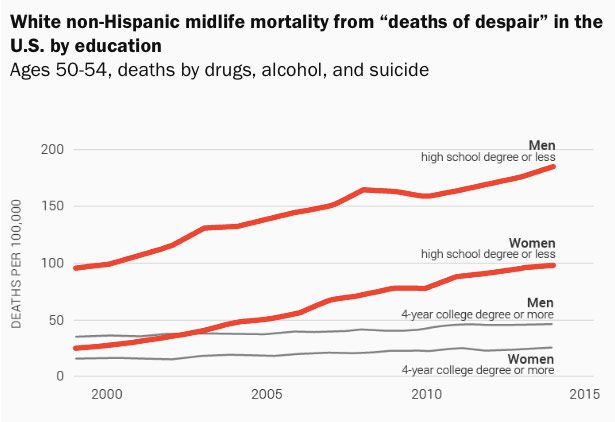

However, only the non-college-educated white population has seen a nearly continuous rise in its mortality rate over the last two decades. And that jump has been driven by a uniquely high spike in “deaths of despair.”

Case and Deaton suggest that, even though African-American workers are more materially disadvantaged than their white peers — and have also suffered greatly from America’s industrial decline — the demographic has found some cause for optimism in their nation’s lurching progress toward racial equality (their data set ends the year before Trump launched his campaign).

By contrast, non-college-educated white workers have seen their economic prospects drop from a higher peak — and no countervailing narrative of cultural progress has arrested their sense of decline. This foreboding can pervade whole communities, and lead their most vulnerable members to seek relief in drinking, drugs, or death.

Case and Deaton argue that the erosion of traditional families and religious communities has contributed to the demographic’s despair, as movement conservatives always insisted. But just as Trump did on the campaign trail, the economists suggest that these breakdowns are “rooted in the labor market.” People don’t struggle economically when they fail to get married and adopt middle-class social norms. They fail to do those things when they struggle economically — building strong familial and communal ties is simply much more difficult when no one with your skill set is earning a living wage.

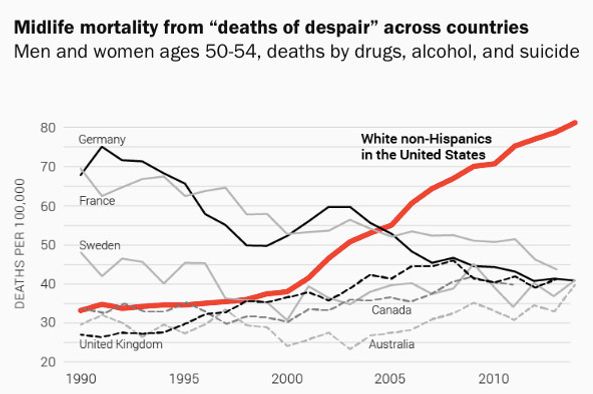

Movement conservatism’s other anti-poverty prescription — instilling self-reliance in the poor by kicking them out of their welfare hammocks — also withers under the paper’s scrutiny. The United States has the thinnest safety net of any major, western nation. And it is also the only such country in which non-college-educated white workers are dying much younger than they used to.

Of course, there are plenty of other factors that contribute to this discrepancy. American physicians began routinely prescribing opioids for chronic pain beginning in the mid-1990s, after a U.S.-based company aggressively marketed oxycodone for that purpose. And America’s singularly high rate of gun ownership likely boosts its suicide rate.

Nonetheless, the rationale behind House Republicans’ push to add work requirements to Medicaid — that providing a minimum standard of health care to the indigent unemployed breeds an unhealthy dependency — is hard to reconcile with the superior health outcomes of workers in European nanny states.

The tenets of movement conservatism have always been belied by the lived experience of working people. But this tension is a lot more conspicuous today than it was when Reagan brought morning to America. Since then, the GOP has grown more radically right wing; income has grown more concentrated at the top; and Republicans have grown ever more dependent on the nonaffluent for votes.

Now, even the GOP base supports more government spending on health care and opposes tax cuts for the rich.

Trump’s rise has alerted some conservatives to the bankruptcy of their ideology. In March 2015, David Brooks attributed the plight of the white working class to a “plague of nonjudgmentalism” — explaining that what the downwardly mobile really needed was a stern lecture on its moral failings:

People born into the most chaotic situations can still be asked the same questions: Are you living for short-term pleasure or long-term good? Are you living for yourself or for your children? Do you have the freedom of self-control or are you in bondage to your desires?

Exactly two years later, Brooks decided that, actually, those people could probably use a stronger social safety net, too:

The central debate in the old era was big government versus small government, the market versus the state. But now you’ve got millions of people growing up in social and cultural chaos and not getting the skills they need to thrive in a technological society. This is not a problem you can solve with tax cuts.

… If you want to preserve the market, you have to have a strong state that enables people to thrive in it. If you are pro-market, you have to be pro-state. You can come up with innovative ways to deliver state services, like affordable health care, but you can’t just leave people on their own. The social fabric, the safety net and the human capital sources just aren’t strong enough.

Republicans can continue putting the superstitions of misanthropic billionaires above the needs of their downscale voters. But in doing so, they will send more “forgotten men and women” to early graves. And, eventually, the righteous people may take the GOP down with them.