Say what you want about Donald Trump — the man is good at inheriting valuable things. First, the mogul built a business career off of his wealthy father’s bequeathments; now, his presidency is being buttressed by the economy Barack Obama left him.

Consumer confidence and comfort are both at decade highs, while private-sector payrolls grew by nearly 300,000 last month, according ADP’s National Employment Report. Sure, one can credit some fraction of these developments to the “animal spirits” Trump unleashed by promising to slash taxes and cut red tape (a.k.a. let coal companies poison our drinking water). But seeing as the president has passed no significant legislation — and took the wheel with the economy already enjoying under 5 percent unemployment — it seems safe to thank Obama for the lion’s share of the good news in America’s business pages.

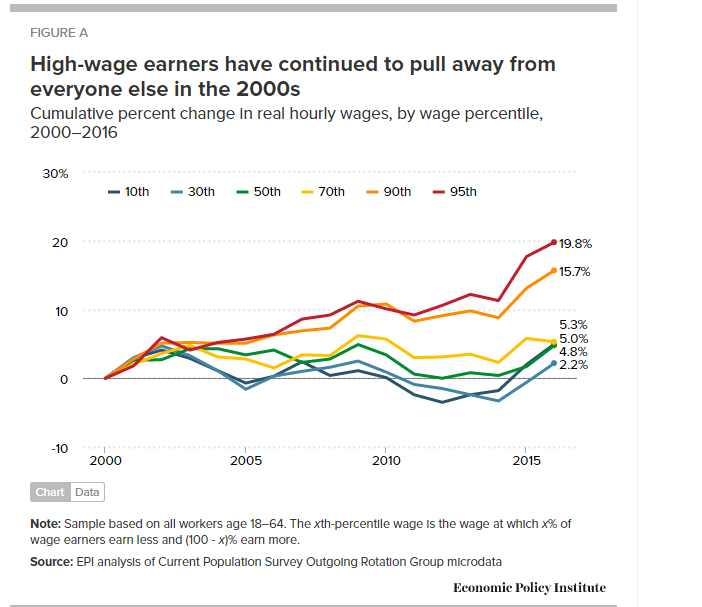

The Economic Policy Institute’s new report on the state of American wages adds further credence to this view. The liberal think tank takes pains to emphasize that the long-term story of wage growth in America is that the rich have been hoarding it all for themselves. But the short-term story is that, by the time Obama decamped from the Oval Office, wages were growing faster at the bottom of the income ladder than they were at the top.

Here are six quick takeaways from EPI’s report.

The recovery is finally reaching the workers who needed it most.

For much of Obama’s presidency, the economic recovery was easy to see on cable-news stock tickers, but hard for most workers to find in their paychecks. In 2010, the top one percent of earners collected up to 93 percent of all the economy’s gains, according to Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez. Incomes among the rest of the population grew by only 0.2 percent that year — after they had fallen by 11.6 percent between 2007 and 2009.

The first six years of Obama’s tenure saw little improvement in the median worker’s earnings, even as the Dow climbed ever-higher. But in 2015, labor markets finally tightened enough to give laborers some bargaining power — and annual median-income growth hit an all-time high.

EPI’s report shows that growth continued in 2016 — thereby narrowing the income gap that had ballooned in the recovery’s early years.

Last year, the median wage rose by 3.1 percent, while workers at the very bottom of America’s income ladder saw their paychecks grow by 2.9 percent — and those in the second-to-lowest percentile saw their incomes swell by 6.4 percent. By contrast, the top 5 percent of earners saw their wages grow by only 1.7 percent.

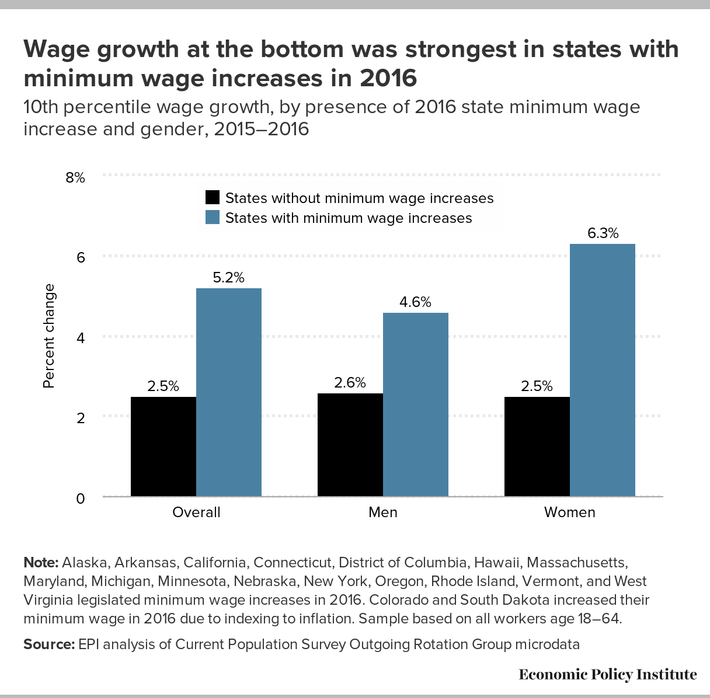

Minimum-wage increases seem to be working.

Part of the story behind the wage growth at the very bottom appears to be a raft of state-level minimum-wage increases that went into effect in 2016. In the 17 states that raised their wage floors, the bottom 10 percent of workers saw their pay increase 5.2 percent; in the rest of the country, that figure was 2.5 percent.

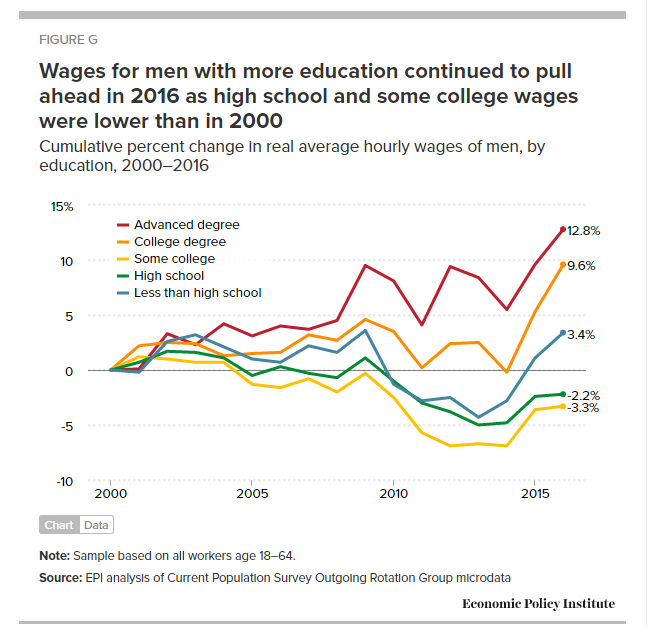

Men without college degrees have had a rough decade.

Since 2000, men who earned some college credits, but lack a bachelor’s degree — and those who finished only high school — have seen their paychecks shrink.

By contrast, wages for women have grown over that period at all levels of educational attainment.

For both genders, a college diploma has been no guarantee of rising prosperity in 21st-century America: The bottom 50 percent of college-educated workers still make less today than they did in 2000 or 2007.

On average, women earn 83 percent of what men do.

“At every education level, women are paid consistently less than their male counterparts, and the gap is particularly striking at higher levels of educational attainment.”

The racial wage gap is still going strong.

Black workers have seen weaker wage growth than whites or Latinos since 2000, and the bottom 60 percent of black workers’ wages remain below their precrisis peak.

Last year’s progress on inequality was a minor victory in a decades-long class war that the one percent is winning.

Since the late 1970s, American policy makers have made it evermore difficult for workers to unionize, drastically reduced enforcement of antitrust laws, allowed minimum wages to stagnate, and prioritized low inflation over low unemployment. The end result of these and other policy decisions is that the top one percent of earners enjoyed a wage growth of 156.7 percent from 1979 to 2015 — while the bottom 90 percent saw their paychecks rise by a mere 20.7 percent, far below the growth in worker productivity.

The Obama administration arguably abetted the growth of wealth inequality in the United States, by failing to take more aggressive action to stem the foreclosure crisis. But the president’s signature health-care law — and the smaller-bore policies of his labor department — redistributed income and economic power from America’s wealthiest to its working class. These measures, along with a tightening labor market, have just begun to arrest America’s descent into a second Gilded Age.

But Donald Trump has a fondness for all things gilded. And the Trump-Ryan agenda amounts to a plan to redistribute as much wealth as (politically) possible to the richest among us. Plus, the Federal Reserve is on the cusp of hitting the brakes on the economy, opting to stymie wage growth for the sake of curbing inflation.

So it probably won’t be long until Trump has turned his inheritance into a garish testament to American inequality. Again.