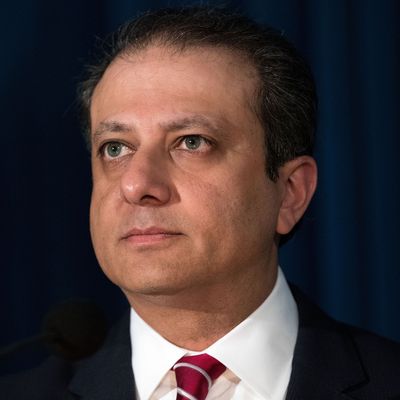

Preet Bharara — still not running for office.

That is the big takeaway from the former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District’s first public appearance since he insisted on being fired by President Donald Trump a little more than one month ago. Since he’s been on the job market, there has been breathless speculation that Bharara might challenge a man he’d just finished (fruitlessly) investigating, Bill de Blasio, in this fall’s mayoral race. Or, even more irresistibly and slightly more plausibly, that Bharara would go up against his great white whale, Andrew Cuomo, in the 2018 race for governor.

In the past three weeks Bharara met with political consultants to talk over the possibilities, and events seemed to line up for just the sort of dramatic unveiling that he’d perfected during nearly eight years of prosecuting Wall Street greedheads and murderous gangbangers. This morning, one of last people Bharara had indicted on political corruption charges — Joe Percoco, former close aide and closer personal friend to Cuomo — went to court and was given a trial date. This afternoon the Times posted Bharara’s first interview since being fired; he called his ouster “a direct example of the kind of uncertain helter-skelter incompetence, when it comes to personnel decisions and executive actions” that have characterized the first months of the Trump administration.

The setting seemed perfect for Bharara to make big news. It was in the Great Hall of Cooper Union, where Abraham Lincoln gave the pivotal speech of his 1860 campaign for president. TV satellite trucks were lined up outside. All 855 seats were filled, some by New York political demi-celebrities, including Silda Wall Spitzer and Zephyr Teachout. The room hummed with what passes for buzz in a crowd of lawyers and good-government types.

Bharara led by flicking jabs at Trump. He joked that the crowd in the room was “a lot bigger than Obama’s crowd … It looks to be about 1.5 million people.” He recounted his dismissal. “Briefly, I was asked to resign, and I refused. I insisted on being fired, and so I was. I don’t really understand why that was such a big deal, especially to this White House. I had thought that’s what Donald Trump is good at,” he said. “How many people remember the dramatic moment on ‘The Apprentice,’ every week, when Donald Trump sat at the conference room table, he manned up, looked the contestant directly in the eye, and said in that voice, ‘Would you kindly submit your letter of resignation?’ I don’t remember that.”

He took a more oblique, though unmistakable, swipe at Cuomo. “Public corruption, I believe we did some of that — nineteen or twenty public officials convicted,” Bharara said. “The dream of honest government still seems a bit far away … And by the way, when a public corruption commission gets abruptly shut down for nonsensical reasons, you’re allowed to be angry and you’re allowed to call B.S. when you see it.”

It wasn’t until about 40 minutes in that Bharara finally let the air out of the electoral balloon — though even that came with a mildly humorous tease that left the door open a crack. “I don’t have any plans to enter politics,” he said, pausing for effect as the audience sighed in disappointment. “Just like I have no plans to join the circus … and I mean no offense to the circus.”

Bharara may find that without the pulpit of a prosecutor’s office or a campaign, it will become difficult for him to hold the attention of the press and the public. Yet it would be too bad if Thursday night’s speech is dismissed for Bharara’s failure to declare a candidacy, or for his reliance on dad humor. The core of his message was an unsexy but essential call for public engagement. “Active citizenship matters,” he said near the end. “It is desperately needed now more than ever … There is a swamp.” Then the jabs at Trump resumed: “To drain a swamp, you need an Army Corps of Engineers, not a do-nothing, say-nothing opportunist who knows a lot about how to bully and bluster, but not so much about truth, justice and fairness.”

Bharara promised he’d stay involved in that effort, though he didn’t say how. Actually, he probably did, when he held up the courtroom as a possible model for democracy, in which “evidence and facts” ruled instead of “insinuation and bad blood.” It was an idealistic, if plaintive, vision for the political system. But it also showed that Bharara seems to know who he is, and how he can best make a contribution — as a lawyer.