Imagine what the political world would look like for Republicans had Hillary Clinton won the election. Clinton had dragged her dispirited base to the polls by promising a far more liberal domestic agenda than Barack Obama had delivered, but she would have had no means to enact it. As the first president in 28 years to take office without the benefit of a Congress in her own party’s hands, she’d have been staring at a dead-on-arrival legislative agenda, all the low-hanging executive orders having already been picked by her predecessor, and years of scandalmongering hearings already teed up. The morale of the Democratic base, which had barely tolerated the compromises of the Obama era and already fallen into mutual recriminations by 2016, would have disintegrated altogether. The 2018 midterms would be a Republican bloodbath, with a Senate map promising enormous gains to the Republican Party, which would go into the 2020 elections having learned the lessons of Trump’s defeat and staring at full control of government with, potentially, a filibuster-proof Senate majority.

Instead, Republicans under Trump are on the verge of catastrophe. Yes, they are about to gain a Supreme Court justice, no small thing, a host of federal judges, and a wide array of deregulation. Yet they are saddled with not only the most unpopular president at this point in time in the history of polling, but the potential for a partywide collapse, the contours of which they have not yet imagined. The failure of the Republican health-care initiative was a sobering moment, when their early, giddy visions of the possibilities of full party control of government gave way to an ugly reality of dysfunction, splayed against the not-so-distant backdrop of a roiled Democratic voting base. They have ratcheted back their expectations. But they have not ratcheted them far enough. By the time President Trump has left the scene, what now looks like a shambolic beginning, a stumbling out of the gate, will probably feel like the good old days.

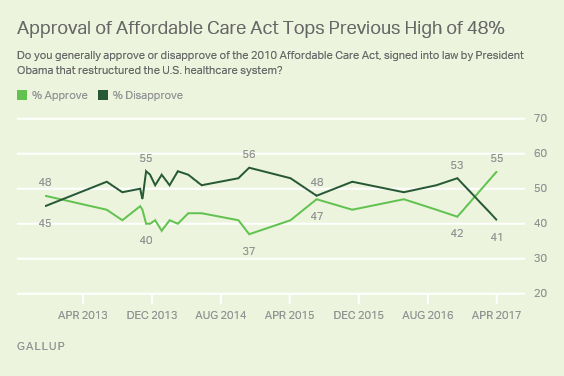

The Republican Party recovered from its cratering under the Bush administration by having the good fortune to lose control of the White House at precisely the moment that a global financial crisis began to inflict deep, ruinous pain upon the public. They used that backlash to gain control of Congress and stymie Obama’s agenda, especially any measures to hasten the recovery or patch up Obamacare, frustrating his supporters. A sense of how deeply the GOP’s position depended upon not holding the White House can be seen in public support for Obamacare. The unpopularity of the law has been the bedrock of the Republican strategy for nearly eight years. Republican control of government has made it … popular.

Health care presents the party with an especially acute dilemma, forcing them to choose between promises they made to the public (lower premiums, lower deductibles, protections for sick people) and conservative ideological commitments that make them impossible. But it is by no means unique. Trump won the presidency by running a campaign that went far beyond the usual sunshine every president sells on the campaign trail. Trump’s populist vision collapsed every policy dilemma into a simple question of negotiating skill that he could solve easily and painlessly. Trump has few clear paths to bolster his popularity while holding together his partisan base. Building the wall will be difficult and time-consuming. Renegotiating Nafta in a dramatically favorable way, as Michael Grunwald explains, is probably impossible. Republican standbys like cutting taxes for the rich and loosening regulations on Wall Street and greenhouse gases are feasible, but all deeply unpopular. All those achievements would also be easily reversible in a way Obama’s biggest policy accomplishments were not. The tax cuts will almost certainly have to expire automatically after a decade. Trump’s deregulatory agenda will be reversed by the next Democratic president.

Speaking of Obama’s policy accomplishments, here’s the best argument you’ll see on why his victories will not be so easily erased.

Trump mortgaged everything to win the election by making promises that he lacked any remotely practical plan to fulfill. The gains for him and his party will be scant, and the political costs of obtaining them high.

Trump could try to break with his party to sign popular bipartisan bills to patch up Obamacare, reform taxes in a way that does not help the rich, and build up infrastructure. But this would cost him the Republican lockstep support he needs to quash investigations into his corruption and campaign ties to Russia. Even a shrewd politician would have difficulty navigating the box in which Trump finds himself trapped.

And Trump is not a shrewd politician. A string of horrifying leaks has depicted a man far too mentally limited to do his job competently. The president is too ignorant of policy — he simply agrees with whomever he spoke with last — to even conduct basic policy negotiations with friendly members of Congress who want him to succeed. Nor does Trump know enough to even identify competent people to whom he can delegate his work. He’s a rank amateur who listens and delegates to other amateurs. (In a normal administration, the hilariously broad portfolio charged to his political novice son-in-law would be seen not as a joke but as a crisis.)

And all of this assumes a relatively straight-line political path. Trump has not yet faced a crisis that isn’t of his own making, as every presidency does with regularity. Trump’s partisan opponents cannot be gleeful at the fallout from an erratic, uninformed president and an understaffed Executive branch trying to manage a major calamity. Partisan politics in a two-party system is a zero-sum exercise. But the world is not a zero-sum place. One Republican staffer, dismayed by Trump’s flailing, told Ezra Klein, “If we get Gorsuch and avoid a nuclear war, a lot of us will count this as a win.”

Avoiding nuclear war should be understood as shorthand for a long list of national disasters that could ensue from Trump’s incompetent leadership — pandemics, wars, natural-disaster response — that would be terrible for the country as a whole and also terrible for the Republican Party. The damage could last a long time.

The last Republican presidency failed so spectacularly it created a generational chasm. Young voters, who mostly followed the same pattern as their elders before George W. Bush, have broken heavily Democratic in every election since 2004. The 2016 election showed slight signs of erosion in the pattern when white voters under 30 supported Trump, 48–43. That is far smaller than the margin by which older whites flocked to Trump, and also far smaller than the margins Republicans will need to sustain among white voters to stay competitive nationally. As the white proportion of the electorate continues to shrink, Republicans will need to either improve among minorities or else steadily increase their share of the white vote, which currently hovers around 60 percent.

But the experience of Trump as president has reversed whatever small momentum the party had gained by 2016. Voters under 30 disapprove of his performance by margins exceeding two-to-one. My recent magazine story describes Trump’s strategy of dividing the country along racial lines, in a way that would allow his party to claim an ever-growing share of the white vote. But the issues Trump hopes to use to attract younger whites to him instead repel them. “In the CNN survey, about three-fourths of white Millennials opposed the border wall and about three-fifths rejected the temporary seven-nation immigration ban,” explains Ron Brownstein. “In the Pew survey, both Millennials overall and young whites were also more likely than any other age group to say the United States benefits from increasing racial and ethnic diversity, more likely to say they personally knew a Muslim, and least likely to say American Muslims were sympathetic to extremism.”

The power of ethnonationalism, which I tried to communicate in the story, is that it manipulates the most base and emotionally accessible ideas about politics. But that power is also a source of danger to the party that tries to weaponize it: If it backfires, it activates equally powerful emotions against it. And while the fight to preserve the American ideal from Trump’s ethnonationalism is hardly assured, there is every sign it will backfire.

Michael Anton’s now-iconic essay, “The Flight 93 Election,” made the case for Trump as a desperation gamble. (Hence the metaphor to a hijacked airline flight whose passengers had to choose a desperate and probably doomed fight over certain death.) Anton, now a staffer in Trump’s administration, saw another four years of Democratic presidencies as the end of white America and conservative America. Most Republicans — even those, like Anton, deeply suspicious of Trump — ultimately agreed. Almost the entire GOP decided its hatred or fear of Clinton overrode their misgivings about their own nominee, and, with varying levels of enthusiasm, supported Trump. They brought disaster upon their country, but as a small measure of compensatory justice, they have also brought it upon their party. By the time Trump has departed the Oval Office, they will look longingly at a staid, boxed-in Clinton presidency as a road not taken.