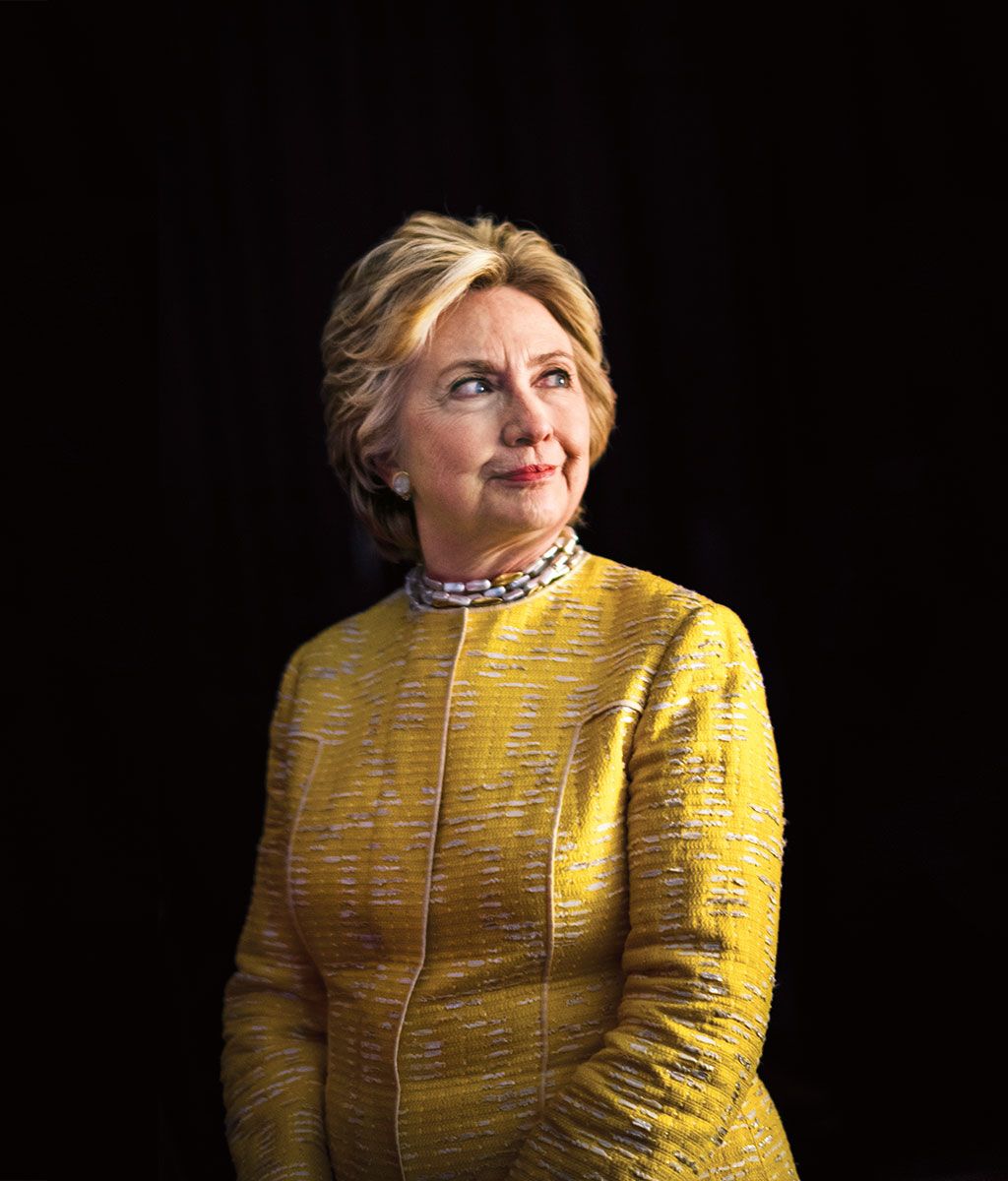

When I walk into the Chappaqua dining room in which Hillary Clinton is spending her days working on her new book, I am greeted by a vision from the past. Wearing no makeup and giant Coke-bottle glasses, dressed in a gray mock-turtleneck and black zip sweatshirt, Hillary looks less Clinton and more Rodham than I have ever seen her outside of college photographs. It’s the glasses, probably, that work to make her face look rounder, or maybe just the bareness of her skin. She looks not like the woman who’s familiar from television, from newspapers, from America of the past 25 years, but like the 69-year-old version of the young woman who came to the national stage with a wackadoodle Wellesley commencement speech in 1969. With no more races to run and no more voters to woo with fancy hair, Clinton appears now as she might have if she’d aged in nature and not in the crucible of American politics. Still, this is not Hillary of the woods. She is reemerging, giving speeches and interviews. It’s clear that she is making an active choice to remain a public figure.

It’s the day after Donald Trump has fired FBI director James Comey, the man who many — including Clinton — believe is responsible for the fact that she is spending this Wednesday in May working at a dining-room table in Chappaqua and not in the Oval Office. Clinton checks with her communications director, Nick Merrill, about what’s happened in the past hour — she’s been exercising — and listens to the barrage of updates, nodding like a person whose job requires her to be up-to-date on what’s happening, even though it does not.

“I am less surprised than I am worried,” she says of the Comey firing. “Not that he shouldn’t have been disciplined. And certainly the Trump campaign relished everything that was done to me in July and then particularly in October.” But “having said that, I think what’s going on now is an effort to derail and bury the Russia inquiry, and I think that’s terrible for our country.”

It will be days before newspapers report that Trump asked Comey to move away from the Russia investigation prior to firing him, but the implications are already clear. History, says Clinton, “will judge whoever’s in Congress now as to how they respond to what was an attack on our country. It wasn’t the kind of horrible, physical attack we saw on 9/11 or Pearl Harbor, but it was an attack by an aggressive adversary who had been probing for many years to figure out how to undermine our democracy, influence our politics, even our elections.” Her hope, in the wake of Comey’s dismissal, is that “this abrupt and distressing action will raise enough questions in the minds of Republicans for them to conclude that it is worthy of careful attention, because left unchecked … this will not just bite Democrats, or me; this will undermine our electoral system.”

Watch: Eight reasons why Hillary Clinton thinks she lost the election.

Talking about Comey, even the day after his firing, is a risky thing for Clinton to do. The last time she did it was in a conversation a week earlier with CNN journalist Christiane Amanpour at a Manhattan lunchtime gala for Women for Women International. Amanpour had asked Clinton about why she thought she had lost the election. “I take absolute personal responsibility,” Clinton replied. “I was the candidate, I was the person who was on the ballot. I am very aware of the challenges, the problems, the shortfalls that we had.” But she had also talked about other factors she believes contributed, citing FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver’s research on the impact of Comey’s October 28 letter. “If the election had been on October 27,” she said, “I’d be your president.”

After the exchange, Clinton and her aides had appeared upbeat. The crowd had been enthusiastic, and there was a sense that Clinton had done something that she has long found difficult in public: She had been herself — brassy, frank, funny, and pissed. But on cable news and social media, another reaction was taking shape. The New York Times’ Glenn Thrush, who has reported on Clinton for years, tweeted “mea culpa-not so much,” suggesting that the former candidate “blames everyone but self.” Obama-campaign strategist turned pundit David Axelrod gave an interview claiming that while Clinton “said the words ‘I’m responsible’ … everything else suggested that she really doesn’t feel that way.” Joe Scarborough called her comments “pathetic”; David Gregory suggested she was not “taking real responsibility for the fact that she was not what the country wanted.” And in the Daily News, Gersh Kuntzman delivered a column that began, “Hey, Hillary Clinton, shut the f— up and go away already.”

Later, Amanpour would tell me how surprised she was by the negative reaction. “The idea that she shouldn’t mention the Comey letter when the entire nation and the most respected statisticians are considering its impact is so strange,” she said. “If she were a man, would she be allowed to mention it? As a woman, I am offended by the double standards applied here. Everyone shrieks that Hillary was a bad candidate, but was Trump a good candidate?”

In the natural biorhythms of popular response to Hillary Clinton, which have been trackable for more than two decades, this is the period during which even her detractors would usually be starting to feel rugged admiration for her. Clinton has typically been most loathed when she is running for office, and most beloved after she has lost but is soldiering on, especially if the loss was sufficiently humiliating. But it’s been six months since the cataclysm of November 8, and feelings about her remain fiercely divided. Social media is awash with Hillary fans who imagine alternative universes in which she’s the president, and Etsy booms with crafts made from the words of her concession speech; yet many of her critics — even those who voted for her — are determined that Clinton bear the mantle of worst politician who ever lived, their evidence being that she lost to … the worst politician who ever lived.

The unusually prolonged pummeling is partly because Clinton’s Election Day loss was not just hers but the nation’s; her defeat this time left us not with an Obama presidency but with an out-of-control administration led by a man so inept — and so reviled — that even (some) Republicans are voicing concerns. The nation is grasping for a way to understand how we got here, and blaming Clinton wholly and neatly takes the heat off everyone else who contributed: from the critics who derided her supporters as empty-headed shills to those supporters who were cowed into secret Facebook groups; from the journalists who treated Trump as a ratings-pumping sideshow and Clinton as the suspiciously presumptive president to all of us who permitted cheerful stories about America’s progress on gender and race to blot out the real and lingering inequities in this country.

The anger at Clinton from some quarters — in tandem with the beatification of her from others — reminds us just how much this election tapped into unresolved and still largely unexplored issues around women and power. In the aftermath, the media has performed endless autopsies. We have talked about Wisconsin, about Comey, about Russia, about faulty messaging and her campaign’s internal conflicts. We have fought over unanswerable questions, like whether Sanders would have won and whether Clinton was particularly mismatched to this political moment, and about badly framed conflicts between identity politics and economic issues. But postmortems offering rational explanations for how a pussy-grabbing goblin managed to gain the White House over an experienced woman have mostly glossed over one of the well-worn dynamics in play: A competent woman losing a job to an incompetent man is not an anomalous Election Day surprise; it is Tuesday in America.

To acknowledge the role sexism played in 2016 is not to make excuses for the very real failings of Clinton and her campaign; it is to try to paint a more complete picture. “I think a lot of people didn’t believe those of us who were yelling that it was hard to elect a woman president,” says Jess McIntosh, a Democratic strategist who was the director of communications outreach for the Clinton campaign. “The fact that that woman lost to the least qualified human being on the planet really kind of drove it home.” At a visceral level, the revelation of sexism’s lingering power is why 3 million women marched in protest on the day after Trump’s inauguration and why more than 13,000 women have expressed interest in running for office since the election.

In some ways, Clinton herself is one of these awakened women; she is much more comfortable talking about gender in the aftermath of her historic run than she ever was during it. Recently, she has even declared herself a member of “the resistance.” “There’s always been this rearguard movement against expanding the circle of opportunity,” she says. “And I believe that a lot of what’s happening now is a resurgence of the anxiety, the fear, the bias that still affects people who are worried that change is coming even faster, that it will have even more consequences.” The unwillingness to acknowledge this backlash, says Clinton, is “part of the reason we are, if not going backward, certainly stalled.”

One evening in April, about a dozen Clinton-campaign alums gathered at Cipriani Wall Street to watch their former boss give a speech at a benefit for New York’s LGBT Community Center. It was a mix of senior and junior staffers — Robby Mook and Jake Sullivan and former finance director Dennis Cheng, plus speechwriters Megan Rooney and Lauren Peterson, chief product officer Osi Imeokparia, Liz Zaretsky and Teddy Goff from the digital team, and Aditi Hardikar, Carl Gray, and Anthony Mercurio from finance. Partway through the lengthy dinner leading to Clinton’s speech, Nick Merrill and Huma Abedin arrived and a signal went up; the staff had been summoned backstage to say hello to the woman whom a few of them hadn’t seen since the election. Ushered into a small room, they clapped as Clinton walked in, then there was a noisy round of handshaking, hugging, and group-picture-taking. When they headed back to their banquet tables to settle in for her speech, two of the men were wiping tears from their eyes.

Mercurio told me that it’d been a terrible week for ex-staffers. Two days earlier, campaign reporters Amie Parnes and Jonathan Allen had published Shattered, a book diagnosing the campaign’s failures as the result of catastrophic internal dissent. Many who were interviewed for this story agreed with portions of the reporting in Shattered — that Clinton listened to too many competing voices, often to the point of inaction; that there were arguments about messaging and resources that turned out to be retrospectively haunting; that the ground game was faulty in some states. What they disagreed with was that any of these problems was unique to their campaign, or that their team was anything other than close and united in their efforts to elect Hillary Clinton. “There was this inference that we were a bunch of mercenaries working for a soulless, distant candidate for whom we felt no genuine affection,” McIntosh would tell me later. “That assertion — that we could not and did not like her — did more to doom us than any internal dissent ever did.”

After Clinton gave her speech, some of the staffers packed into a van and hitched a ride to Chappaqua, where they would spend the night before a day of working on the book. The rest, including Mook and Cheng, headed for a bar, where they drank and laughed and looked at their phones, a habit that has been hard to break. Few at the bar were still on Clinton’s payroll, but they all seemed devoted to her, and to each other — veterans of a losing battle. “We were really good and humane to each other,” says Rooney. “And we really loved her. We still do.”

Affection for her campaign staff is one reason Clinton claims she will not point fingers at her own team in assessing her loss. “I will never say anything other than positive things about my campaign,” she tells me in Chappaqua. “Because I love the people that led it, worked in it.”

Besides, she argues, “what I was doing was working. I would have won had I not been subjected to the unprecedented attacks by Comey and the Russians, aided and abetted by the suppression of the vote, particularly in Wisconsin.” She agrees that there are lessons to be learned from her campaign, just not the same ones her critics would cite. “Whoever comes next, this is not going to end. Republicans learned that if you suppress votes you win … So take me out of the equation as a candidate. You know, I’m not running for anything. Put me into the equation as somebody who has lived the lessons that people who care about this country should probably pay attention to.”

Piecing together what happened, with six months of perspective, Clinton says she thinks she “underestimated WikiLeaks and the impact that had, because I thought it was so silly.” Those hacked emails, dripped out over weeks, says Clinton, “were innocuous, boring, inconsequential. And each one was played like it was some breathless flash. And so you got Trump, in the last month of the campaign, talking about WikiLeaks something like 164 times; you’ve got all his minions out there, you’ve got the right-wing media just blowing it up. You’ve got Google searches off the charts.”

Clinton has been looking at where some of the Google searches for WikiLeaks were coming from. “They were from a lot of places where people were trying to make up their minds,” she says. “Like, ‘Oh my God, I kinda like her, I don’t like him, but she might go to jail. And then what about all this other stuff?’ It was just such a dump of cognitive dissonance …” Clinton trails off and then smiles and nods to herself. “I have a lot of sympathy for voters in a lot of places I didn’t win,” she says. “Because I can see how hard it was.”

The press, she believes, didn’t make it any easier. “Look, we have an advocacy press on the right that has done a really good job for the last 25 years,” she says. “They have a mission. They use the rights given to them under the First Amendment to advocate a set of policies that are in their interests, their commercial, corporate, religious interests. Because the advocacy media occupies the right, and the center needs to be focused on providing as accurate information as possible. Not both-sides-ism and not false equivalency.”

The impulse toward false equivalency is only getting worse, in her opinion. “The cable networks seem to me to be folding into a posture of, ‘Oh, we want to try to get some of those people on the right, so maybe we better be more, quote, evenhanded.’ ” When I mention MSNBC’s hiring of conservatives including George Will, and the New York Times’ new climate-change-skeptic opinion columnist, Bret Stephens, her brow furrows. “Why … would … you … do … that?” she says. “Sixty-six million people voted for me, plus, you know, the crazy third-party people. So there’s a lot of people who would actually appreciate stronger arguments on behalf of the most existential challenges facing our country and the world, climate change being one of them! It’s clearly a commercial decision. But I don’t think it will work. I mean, they’re laughing on the right at these puny efforts to try to appease people on the right.”

To be sure, Trump got plenty of negative coverage in the press as well, but, during the campaign at least, the negative stories didn’t seem to stick to him with the same adhesion. And even now, as investigations of his administration’s connections to Russia splash across front pages, the Times has launched a new feature, a weekly call to readers to “Say something nice” about him. I ask Clinton if she’s seen it. “I did!” she says with a wide smile, taking a beat. “I never saw them do that for me.”

By Election Night, Clinton says, she knew it was going to be close but thought she would be able to “gut it out.” “I was as surprised as anybody when I started getting returns. Because that’s not what anybody — with a couple of outliers — saw in the data. And the feel was good! We had good crowds, we had lots of energy and enthusiasm, and I thought we were going to pull it off. And so did the other side, by the way. They did not believe they were going to win.”

As staffers and friends began to melt down with shock and grief, Clinton, by all accounts, remained preternaturally calm. One staffer speculated that she was able to do so because she is a person who often expects the worst and does not trust the best: “It was an example of reality rising to meet her expectations.”

“I remember having conversations with her which were gut-wrenching to me,” says Mook of that night. “Saying to her, ‘The math isn’t there. It doesn’t look like we can win.’ She was so stoic about it. She immediately went into the mode of thinking, Okay, what do we do next?”

Speechwriters Dan Schwerin and Megan Rooney realized that they were going to have to produce a concession speech. Rooney had drafted one and stuck it in a drawer. As the evening wore on, they started working on it. By the time the results were certain, Clinton and her advisers felt that it was too late to make a speech; she wanted to consider carefully what she had to say, and went back and forth with her team about the stance to take toward Trump. When Schwerin and Rooney came to her suite at the Peninsula Hotel the next morning to go over the draft, Clinton was sitting in her bathrobe at the table. She had slept only briefly, but she was clear: She wanted to take a slightly more aggressive approach, focusing on the protection of democratic norms, and she wanted to emphasize the message to young girls, the passage that would become the heart of her speech. As the pair of writers left her room and walked down the hall, Rooney turned to Schwerin and said, “That’s a president.” Schwerin remembers: “Because here, in this incredibly difficult moment, she was thinking calmly and rationally about what the country needs to hear.” Schwerin said that until then he had held it together. “But I kind of lost it then.”

“I think she has never gotten enough credit for how definitive and clear that speech was, what a smooth transfer of power she was facilitating,” says Mook. “It was so close, there were so many allegations, particularly about irregularities, and she never wavered on the idea that she had to definitively concede and make sure there was a smooth transition of power.”

To hear Clinton tell it, focusing on the immediate tasks was what saved her. “This was a crushing, devastating blow,” she says now. “I just thought we had to get through this with a level of dignity and integrity, and there’d be plenty of time to try to figure out what went wrong and what we could have done differently, but for that moment we just had to stick to the ritualistic process: Okay, when I was sure, I have to call Trump. I want to call Obama. And then I have to figure out what I’m gonna do the next day … I had to get through that before I could go, ‘What the hell just happened?’ and be angry and upset. And be disappointed and feel I let people down and feel everything that I felt.”

She was still in the ritualistic-process mode when she attended Trump’s inauguration. People close to her told me that she’d had doubts about being able to make it through without visibly losing control. “Oh,” says Clinton, “it was hard. It was really … difficult.” But “at the time, we hoped that there would be a different agenda for governing than there had been for running.”

Of course, it quickly became clear from Trump’s speech that there would be no change in strategy. A look of disgust crosses Clinton’s face as she recalls it. “It was a really painful cry to his hard-core supporters that he wasn’t changing,” she says. “The ‘carnage’ in our country? It was a very disturbing moment. I caught Michelle Obama’s eye, like, What is going on here? I was sitting next to George and Laura Bush, and we have our political differences, but this was beyond any experience any of us had ever had.”

I ask her about the report that Bush had said of the speech, “That was some weird shit,” and her eyes light up. “Put it in your article,” she says. “They tried to walk back from it, but …” Did she hear it herself? I ask. She raises her eyebrows and grins.

Remembering Election Night and the inauguration, I can’t help but think that Clinton’s ability to set aside her own feelings might be useful but perhaps not entirely healthy. I ask her if she’s ever been in therapy, and she shakes her head. “Unh-uh. No. I have not.” When I express surprise, she allows, “Well, we had some marital counseling in the late ’90s, around our very difficult time, but that’s all.”

She shrugs. “That’s not how I roll. I’m all for it for anybody who’s at all interested in it. It’s just not how I deal with stuff.”

When she entered the 2016 race, Clinton says, she had hoped that “a lot of the rawness of being a woman competing for the presidency would have dissipated” in the eight years since she had last run. What she found was that indeed, “a lot of the explicit stuff” — the nutcrackers, the television pundits who compared her to their carping ex-wives, the opponents who made fun of her outfits during debates — “had somewhat diminished, but a lot of implicit [bias] was just raging below the surface.” For Clinton, the online commentary, the more subtle but also more intimate social-media disparagement, offered “the revelation that there were still very deep, raw feelings about gender that had not been resolved.”

Early in the campaign, Clinton spoke to historians, psychologists, and others who’d examined gender bias about what she should expect. “They were very clear that this was going to be an uphill battle,” she says. Particularly dire were the warnings from Sheryl Sandberg, the Facebook COO whose 2013 book Lean In had become a flash point in discussions around feminism, class, capitalism, and the roadblocks that remain for ambitious women. “The takeaway from Lean In,” says Clinton, “is that there is a stark difference between men and women when it comes to success and likability. So the more successful a man is, the more likable he is. The more successful a woman is, the less likable she is. And it’s across every sector of society.”

Sandberg predicted to Clinton that her reception during the campaign would be very different from the 69 percent approval rating she’d gained as secretary of State. “Sheryl was right-on,” says Clinton. “Once I moved from serving someone — a man, the president — to seeking that job on my own, I was once again vulnerable to the barrage of innuendo and negativity and attacks that come with the territory of a woman who is striving to go further.” So how did knowing that ambition is negatively correlated with likability for women affect Clinton’s approach in seeking the most powerful office in the land?

“Well, this is the joke,” she says. “You gotta be authentic! So you go out and try to be as effective as you can in presenting yourself and demonstrating the qualifications you have for the job, but you’re always walking a line about what will find approval from the general population and what won’t. It’s trial and error.”

Her team recalled the persistent feeling of being in uncharted territory. As McIntosh says, “Should she have showed more emotion? I don’t know. We don’t know whether women who show less emotion get to be the president. Should she have been less hawkish? I don’t know. We don’t know if we can elect a pacifist woman president. We can’t point to where she diverges from a path that other women have taken because she was charting that path, and that might fuck with your analytics a bit, as it turns out.”

The campaign was sometimes frustrated by the fact that Clinton couldn’t play the same game as her opponents. “Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump both excelled at channeling people’s anger,” says Schwerin. “And there was a way in which this anger was read as authentic. But there’s a reason why male candidates can shout and are called passionate, and if a woman candidate raises her voice to whip up a crowd, she’s screeching and yelling.” Clinton understood this, says Schwerin. “So she’s controlled. She doesn’t rant and rave, she’s careful. And then that’s read as inauthentic; it means that she doesn’t understand how upset people are, or the pain people are in, because she’s not angry in the way those guys are angry. So she must be okay with the status quo because she’s not angry.”

Clinton says the second debate with Trump, during which he loomed menacingly behind her, was one of the hardest situations of the whole campaign. “Because what he was doing was so … uh …” — she pauses to search for words — “so personally invasive: following me, eyeing me.”

She considered confronting him, turning around and saying, “Get away from me!” But she figured that would just give him what he wanted. “I saw him destroy all of his Republican opposition who eventually tried to confront him on a debate stage, and he reacted with such contempt. He will gain points, and I will lose points.” Acknowledging how tight her grip on the microphone was during that debate, Clinton says, “Think of all the times where you are either mentally or physically gripping yourself, [willing yourself] not to respond, not to lash out, not to display the anger that you feel, because you know it will redound to your detriment. So you swallow it. You try to be honest with yourself, to know you’re feeling it but then say, ‘Okay, I’ve got a goal here and I’m not going to get knocked off-balance.’ ” Clinton maintained control. “So I ended up with another ‘win,’ ” she says. “But I also ended up with him really satisfying a lot of his potential voters. One of these guys, I can’t remember who” — it was Nigel Farage — “said, said, ‘Oh, he was the alpha male! He was the big gorilla in the …’ — whatever they call gorilla groups! I think that for people already committed to him, they loved it.”

But was she right that she couldn’t have expressed her anger in that debate? There are plenty of people who yearned for Clinton to get mad; during the campaign, an imagined litany of Clinton’s fury titled “Let Me Remind You Fuckers Who I Am” went viral. “Oh, I am [pissed],” she says. But as a woman in public life, “you can’t be angry for yourself. You just can’t. You can be indignant, you can be annoyed, you can be frustrated, but you can’t be angry … I don’t think anger’s a strategy.”

You mean it’s not a strategy for you, I clarify. “For me, yeah.” She pauses. “But I don’t think it’s a good strategy for most people.”

But this was an election that was, in many ways, about anger. And Trump and Sanders capitalized on that.

“Yes.” Clinton nods. “And I beat both of them.”

Thirty-six hours after her interview with Amanpour and the opprobrium that followed, a steamrollered Clinton walked into a downtown event space for the Ms. Foundation’s Gloria Awards, looking like Charlie Brown having just had the football yanked away again: Gone was the loose, open Clinton, back was the tight, fake distance and distrust.

Clinton dutifully did a photo line with Gloria Steinem and the co-chairs of the Women’s March, some of whom have been her fierce critics, and was then mobbed by a group of former staffers. “It’s a reunion!” she bellowed gamely as this evening’s group — including her former director of engagement De’Ara Balenger, former deputy national political director Brynne Craig, and former digital-outreach chair Zerlina Maxwell — piled on. But Clinton looked strained, tired, as she moved away from them to go over speech logistics.

As the young women from her campaign formed a knot and began a heated conversation about the blowback Clinton had received over the past few days, their former boss started to edge closer to where they were standing, her ear turned slightly to their exchange. The conversation got more boisterous and more profane, and Clinton got closer. As the group remarked on the way Clinton’s critics had whipped each other into a frenzy, she could no longer help herself. “Well of course they did,” she chimed in. “They’re boys.”

The conversation continued, its subject now present and nodding along. Clinton asked if the group had heard that searches for the word misogyny rose by 10,000 percent after Amanpour used the word. Can you believe that six months after this election, people still didn’t know what misogyny means? I asked in reply. A smile barely flickered around Clinton’s lips before she deadpanned: “Why, yes. I guess I can believe that.”

Clinton has a complicated relationship with feminism, and with women more broadly. While Clinton won black, Latina, and Asian women by huge margins, 53 percent of white women preferred the candidate who called women pigs and dogs to the one from their own demographic. Of course, no Democrat since Bill Clinton has won white women, and Hillary did better with them than Obama did in 2012. But the reminder of this old dynamic — that male power over a majority population, women, would not be possible without the willing support of members of that majority — came as a nasty surprise to some on the campaign.

“The thing that stood out to me the most,” says Mook, “is when we would hear women say, ‘Do we really want a woman president?’ And we would find that women were much more ready to say that than men, and that really surprised me because I guess it just never occurred to me that anyone would want to disqualify themselves.”

The campaign was determined to be better at emphasizing the historic nature of Clinton’s run than it had been in 2008, when strategist Mark Penn had advised Clinton to run like a man, but striking the right note about women — to women — remained tricky. Early conversations with persuadable women voters showed that they would balk at framing Clinton’s candidacy as historic, citing fears that such an argument would alienate men.

Then again, after Trump accused Clinton of “playing the woman card,” the campaign produced actual wallet-size “Woman Cards” that could be purchased for a dollar and proved to be its greatest merchandising and PR success.

Though you might not know it from the media coverage, there were many, many women who not only voted for Clinton but were excited about it. “Look at all of the deep dives into who exactly Trump voters were, what motivated them, where they had been let down, what they believed,” says McIntosh. “Look at the coverage of Bernie Sanders’s supporters: Who’s filling the stadium, what gender and age and race were they? Those stories did not exist about enthusiastic Hillary voters even though there were more enthusiastic Hillary voters than for the other candidates. That lack of validation made it easier for the brutal response women experienced when they said they liked her.”

The brutal response McIntosh is referring to was the way in which expressions of unreserved support for Clinton were often met with accusations of featherbrained fangirl-dom, or vagina-voting. This dynamic led plenty of supporters to shut up about their enthusiasms or to take them underground, to their online clubs. There was “no reason for people to believe that there were actually millions of people who genuinely adored her,” says McIntosh. Another story that never really landed: “The majority of our donors were women,” says Mini Timmaraju, Clinton’s former director of the women’s vote. “That’s never happened before in a presidential campaign.”

More than one male staffer spoke of a dark joke from the campaign, one that reflected their awareness of how little credit was given to Clinton and the women who worked for and supported her. The joke was that if Clinton won, the story would be about how the brilliant men running her campaign had managed to drag her limp body over the finish line.

In mid-April, Clinton was in a classroom at La Guardia Community College, waiting for Andrew Cuomo, who was about to sign into law his college-affordability legislation. She was fretting about everyone’s wardrobe — she said she’d just moved her winter clothes out of her closets but was still struggling with layering — and admiring the reversible pantsuit that Huma Abedin was wearing, urging her to show off the seams and details. It’s made by a company founded by two young women who were supporters, and Clinton was hawking for them like a garment-industry old-timer: “They make them all in New York, and they’re not unreasonably priced!” she said. “I just want to support more of these young-women-owned businesses, and I think it’s so sweet that they are making pantsuits!”

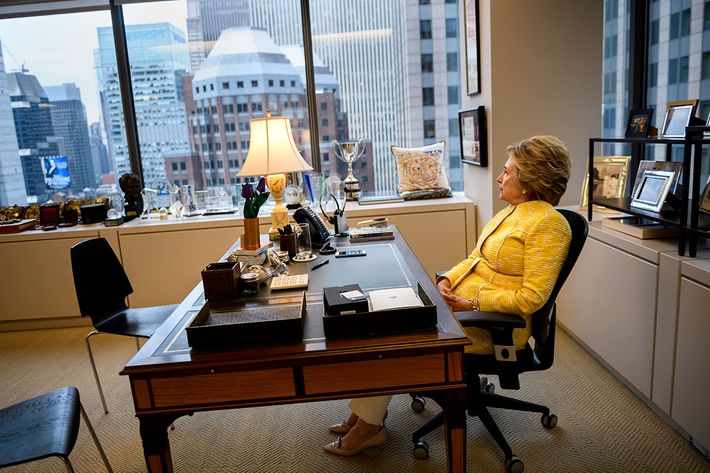

Clinton’s focus on seasonal wardrobe choices and cleaning out her closet was evidence of how odd her life is now. For the first time in a long time, she does not have a crowded schedule of events; some weeks include multiple commitments and writing time, but there have been comparatively vast stretches during which there has been very little to do.

The slow pace was especially uncanny in the early weeks of the Trump administration, when the new president was issuing one executive order after another while Clinton and her staff could only watch in paralyzed horror. “It was like the inverse of Veep,” Merrill says. “Instead of an unqualified person being thrust into a position of huge responsibility, there was a hugely overqualified person with no responsibilities.”

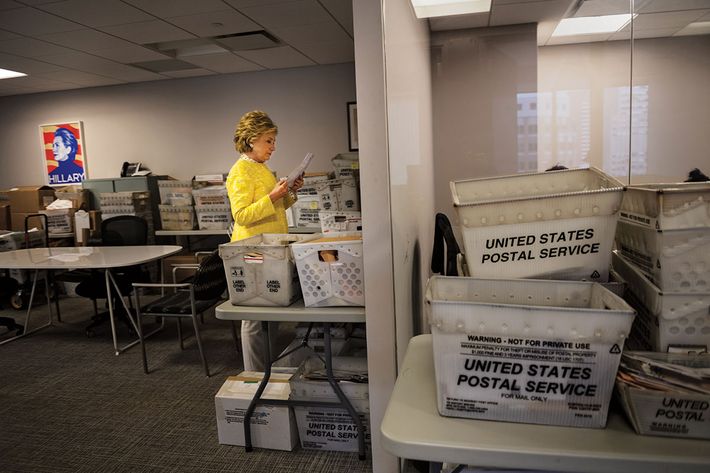

Yes, she did a lot of walking in the woods and around Chappaqua. And yes, she caught up on her sleep — she speaks often these days of the benefits of rest and good food and being outdoors. She answered mail and had scores of off-the-record exit-interview meetings, and she and Bill saw most of the shows currently on Broadway. They have dinners together and spend time with their grandchildren, whose jungle gym is right outside the window where Hillary works. Bill has recently re-immersed himself in the Clinton Foundation, but Hillary is not involved in its day-to-day operations, instead focusing on her writing and speaking engagements. On trips to Texas and to Wellesley, and in the comfortable Times Square office she has kept since 2013, she is accompanied by those staffers who’ve stayed on: Merrill and Abedin; two young assistants, Opal Vadhan and Grady Keefe; and Robert Russo, who works on her correspondence.

Simon & Schuster plans to publish Clinton’s book on a rushed schedule in the fall. Billed as a collection of essays riffing on her favorite quotations, it’s a project that sounded anodyne from the press release. But Clinton’s drive to get some of her thoughts on the election out of her head, along with the urging of friends that she should let rip, has led her to work toward a fuller chronicle. She has called the process, which is taking up most of her time these days, “excruciating.”

Clinton and her team understand that she will be excoriated for whatever she writes. “There’s never going to be enough self-blame for the people who demand it,” says Schwerin of the book. The appetite for the abasement of Hillary Clinton has long been insatiable. Over the course of 25 years, stories about whether Clinton should apologize, about how she apologized, or about her unwillingness to apologize — for everything from dissing Tammy Wynette to voting for the Iraq War — have been frequent and fetishistic. In November, Clinton became the first person to lose a presidential race to say “I’m sorry” for the loss in her concession speech. A press release for a new collection of her emails and speeches to Goldman Sachs, entitled How I Lost and with a foreword by Julian Assange, reads as an apology from Clinton for being “incapable of beating even a sexist dumbass,” as if sexist dumbasses were easy to defeat in America.

When I ask Clinton about the eagerness to blame her and her alone for the election result, she gets impatient. “Oh, I don’t know, you’d have to talk to a psychologist about it. There’s always, what’s that word … Schadenfreude — ‘cut her down to size,’ ‘too big for her own britches’ — I get all that. But I don’t see this being done to other people who run, particularly men. So I’m not going to engage in it. I take responsibility, I admit that I’m not a perfect candidate — and don’t know anybody who was — but at the end of the day we did a lot of things right and we weathered enormous headwinds and we were on our way to winning. So that is never going to satisfy my detractors. And you know, that’s their problem.”

There’s a lot of gallows humor around Clinton these days. Waiting for Cuomo at La Guardia, she was talking about what it’d been like looking back on all the editorial endorsements she got during the campaign, some from even conservative papers. “I want to be buried with my editorial endorsements,” she said with a laugh. “I want an open casket and they can all be piled on top of me. You won’t even be able to see my body.” Abedin and Merrill joined in. “I can’t seem to get a last look at Hillary, but here’s the Cleveland Plain Dealer!” shouted Merrill, imagining the funeral.

The joke was cut short when Cuomo walked into the room. Suddenly, Clinton’s wryness was gone and she was high-pitched and effusive. They talked about Easter, about how she’d like to fill some of those plastic eggs for the kids but Chelsea told her that Charlotte can’t yet eat jelly beans. Cuomo suggested doing “those marshmallow things instead.” It was all very ordinary and small-talk-y until you remembered that Donald Trump is president and Hillary Clinton is discussing the merits of Peeps versus jelly beans.

When the event was over, as Clinton was leaving La Guardia, an office full of women started shrieking from behind a door that had been closed by security. Clinton paused, then opened the door to let them in. “Oh my God, she opened the door herself,” one of them screamed as they huddled around her, taking selfies and shouting, “Don’t give up, Hillary!” After Clinton left, one of the women shouted across the office, “I want her to run again!” But when I asked her name, she looked stricken. “I just hope she keeps speaking out,” she said and turned away.

Almost everywhere Clinton goes, it seems, someone starts crying. It’s not just friends and staffers. And though it was more intense in the weeks immediately following the election, it hasn’t entirely let up. At restaurants, in grocery stores, on planes, and in the woods, there are lines of people wanting selfies, hugs, comfort.

“It’s been unlike anything I’ve ever seen,” she says. “I mean, it doesn’t end. Every time I’m in public. I was having lunch with Shonda Rhimes last week and a woman stopped at the table — well-dressed, probably in her 40s or 50s — and she said, ‘I just can’t leave this restaurant without telling you I’m just so devastated,’ and she just started to cry. I was on the other side of the table, or I would have done what I have done countless times since the election, which is just put my arms around her. Because people are so profoundly hurt. And it is, yes, predominantly women. But men say it in a different way. Men are, ‘I voted for you and I don’t know what the hell happened.’ But for women who supported me or who feel bad that they didn’t, not because they voted for somebody else but because they didn’t vote …”

This is the dynamic that is perhaps the most intense for Clinton. “Not so much anymore, but in the immediate aftermath, from after the election to probably the first of the year,” she says, “I had people literally seeking absolution.”

I look at her, surprised. “Oh, yeah,” she says, nodding. “ ‘I’m so sorry I didn’t vote. I didn’t think you needed me.’ I don’t know how we’ll ever calculate how many people thought it was in the bag, because the percentages kept being thrown at people — ‘Oh, she has an 88 percent chance to win!’ I never bought any of that, but lots of people did.”

In particular, Clinton recalls one night at the theater. “It was intermission, and a woman came over holding the hand of a young woman. She literally dragged her daughter over to see me. And she said, ‘My daughter has something to tell you … Tell her.’ And this girl says to me, ‘I am really sorry; I didn’t think you needed my vote and I didn’t vote.’ And her mother says [yelling], ‘Yes, she didn’t vote! You didn’t vote! You’re part of the problem!’ I said, ‘Okay, well, next time I hope you’ll vote.’ And she said, ‘But I marched!’ ” Here Clinton smiles. “And I said, ‘I’m really glad you marched. I’m so glad you marched.’ ”

There is twisted irony in the fact that the millions of women who poured onto the streets in January would have changed the outcome of the election had they come together before November, yet the march never would have happened had Hillary Clinton not lost the presidency. This is often the backtracking path of progress for the women’s movement in this country. Recall Anita Hill’s claims of sexual harassment by Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas in 1991; women suffered a material loss with long-lasting consequences when Thomas was confirmed in spite of Hill’s testimony. (Thomas’s part in gutting the Voting Rights Act was likely a contributing factor to Clinton’s 2016 loss.) But the fury that Hill’s treatment provoked in women proved catalytic. In 1992, a record number of women ran and were elected to Congress, and EMILY’S List blossomed into one of Washington’s most powerful political institutions.

Similarly, since the election, the outcry, the march, the organizing, the resistance “has been really powerful,” says Clinton. She is hoping to build on the momentum with her new 501(c)4, Onward Together, which is supposed to direct the fire hose of fund-raising dollars that powered her campaign to grassroots groups working to oppose the Trump administration. One of those groups is Emerge America, which trains female candidates to run for office. Another is Run for Something, a group designed to draw young people into politics; its 27-year-old co-founder Amanda Litman worked on Clinton’s digital team. “It has to be sustained,” says Clinton. “And here is my big worry. The other side is sustained by greed and hate and power and ideology, and they never quit. They get up every day looking to take advantage and drive their agenda forward.”

Having been on the receiving end of the right’s anger for decades, Clinton knows from relentless hate. They still chant “Lock her up” at Trump rallies, just as they did at the New York Stock Exchange as she gave her concession speech. “You know, these guys on the other side are not just interested in my losing, they want to keep coming after me. I mean, think about that for a minute. What are they so afraid of? Me, to some extent. Because I don’t die, despite their best efforts. But what [really drives them] is what I represent.”

Clinton knows that had she won, she would have governed in a time of deep anti-feminist backlash. “You know what?” she says. “I would have loved to have had that problem. Look, I know what’s out there. I have lived it. I have come of age at a time when expectations and norms and institutions changed for women.” Clinton understands that for many in America, she embodies those changes and has spent her career absorbing the anxiety they provoke. “Part of what my opponent did, which was brilliant,” she says, “was blow the top off: You can say whatever you want about anybody else, and I’ll tell you who to be against. I’ll tell you who you should be resentful of.” The stories her campaign tried to tell, she says, “were boring in comparison to the energy behind malicious nostalgia.”

Clinton is no longer trying to win Ohio (which is a good thing, because she lost it by eight points), but she still is trying to figure out how to tell those Democratic stories. “Forget the detractors, forget the kibitzers, forget the nasty guys and women,” she says of what the left must do to move forward. “And figure out how we communicate with people who feel what we’ve been talking about, who know there’s something much bigger than me and my campaign. The values that 66 million people voted for are worth fighting for.” But she acknowledges that the message is more difficult than ever to get across: “We’re up against suppression, we’re up against an even greater domination of the media by the right. We are up against the propaganda machine. I mean, they have a reelect campaign already started! They have raised millions of dollars. They know that they’re in a fight.”

Tapping into a comparably powerful energy is one of the challenges ahead for the left, says Clinton. “We just have a different set of values. Part of our challenge is to recognize that, honor that, but keep people focused on the fact that we are in a fight for the future. We can’t be them, and we have got to be better at being us.”

On a cool May morning, Clinton returned to Wellesley to give another commencement speech. It was 48 years since the address that introduced America to the woman who would eventually come within 78,000 votes of the presidency, and it was just over six months since the speech in which she conceded that her dream of being the first female president would never be fulfilled. It was clearly an emotional experience for Clinton. When her voice got scratchy and she asked for a lozenge, she joked, “We’ll blame allergies instead of emotion.”

She acknowledged to all the younger versions of herself in the crowd that “things didn’t go exactly the way I planned,” just as things may not go as they plan, either. “But you know what? I’m doing okay … Long walks in the woods. Organizing my closets. I won’t lie: Chardonnay helped a little, too.”

But as much as she joked about her loss, it was not a speech of retreat. Here on her home turf, Clinton was much more fiery than she had been during and right after the campaign, drawing sharp comparisons between the era in which she was at Wellesley and now, noting that back then “we were furious about the past presidential election of a man whose presidency would eventually end in disgrace with his impeachment for obstruction of justice after firing the person running the investigation into him at the Department of Justice.”

She reiterated the message to young women in her concession speech: “You are valuable and powerful and deserving of every chance and opportunity in the world. Our future depends on you believing that,” she said. “Don’t be afraid of your ambition, your dreams, or even your anger. Those are powerful forces. … Be bold, try, fail, try again, and lean on each other, hold on to your values. Never give up.”

*This article appears in the May 29, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.