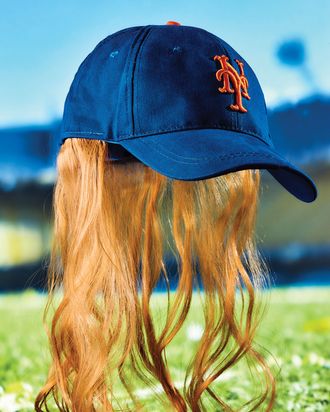

One of the more absurd, madcap musical chairs of recent Mets vintage — and, boy howdy, have there been plenty — was April’s foofaraw involving an injury to pitcher Noah Syndergaard.

Last year, the Asgardian ace threw his fastball harder on average than any starter in baseball, a blazing, terrifying, that-doesn’t-really-seem-fair thunderbolt that consistently ran to an almost-impossible-to-believe 97.6 mph, the highest in baseball history. This spring, he showed up to training camp boasting that he’d added 17 pounds of muscle that would allow him to throw still harder. And he was as good out of the gate as any Met has been in decades (three starts, 19 IP, 2 ER, 20 K, 0 BB). Then he began complaining of a “dead arm” but refused to submit to an MRI, declaring that he knew his godlike body best and that he was fine. The Mets believed him — partly because they wanted to and partly because, as Mets general manager Sandy Alderson put it, “I can’t tie him down and throw him in the tube” — and let him make his next start. You probably know what happened next: Syndergaard left the game early, in pain, and afterward learned he’d miss at least two months.

According to research by baseball writer Joe Sheehan, here are the 12 hardest-throwing starting pitchers in recorded Major League Baseball history (since 2002, when velocity was first reliably quantified and documented): Noah Syndergaard (97.6 mph), Yordano Ventura (96.5), Nathan Eovaldi (95.8), Gerrit Cole (95.6), Carlos Martinez (95.6), Garrett Richards (95.5), James Paxton (95.5), Stephen Strasburg (95.4), Matt Harvey (95.4), José Fernandez (95.2), Felipe Paulino (95.2), and Wily Peralta (95.1).

In a macabre coincidence, two of them, Ventura and Fernandez, died in tragic accidents within the past eight months. Felipe Paulino aside, all the others are still active pitchers. Which is to say: Pitchers are throwing harder at this moment than at any other time in baseball history. You will also note that 11 of the 12 — the only exception (so far) being St. Louis’s Carlos Martinez — have had some sort of serious elbow problem. They tally seven Tommy John surgeries; four, including Syndergaard, have already gone on the disabled list this season.

Sheehan cleverly argues that high velocity in baseball — specifically the 95-mph-average threshold for starting pitchers — is basically like the Demon in The Right Stuff, the sound barrier that “no man could ever pass.” And the stats back him up. If you want to be a successful Major League Baseball pitcher, particularly in today’s game, you have to throw as hard as you possibly can. But if you do that, you will shred your elbow.

That injury risk is, now, simply the price of admission. (It also, it’s worth noting, makes the Mets’ long-term strategy of devoting their resources to young, hard-throwing starting pitchers seem particularly insane. You can’t build a future on power arms; you can barely build a present.) Average pitch velocity in the game has risen nearly two miles per hour in the past decade alone, and it has led to what has become known as the “three true outcomes” style of baseball, in which strikeouts, walks, and home runs — the three plays that do not involve fielders — are taking up a larger percentage of at-bats than ever. And strikeouts, in particular, are higher than at any other time in baseball history. Strikeouts result from velocity. Velocity results in injury. Baseball is incentivizing an activity that is tearing its young pitchers’ arms apart. Believe it or not, this is almost by design.

About 15 years ago, NFL general managers started to realize that running backs, long one of the celebrity skill positions in the sport, were both injury-prone and replaceable; rather than building an offense around a franchise back, they ran their players into the ground and then discarded them. We haven’t yet seen a cultural shift in the status of starting pitchers in baseball, but one might be just around the corner. Because here’s another factoid to keep in mind about those 12 pitchers who throw harder than anyone else in the documented history of the sport: Most of them haven’t made it to a payday in free agency.

Oh, sure, they made a few years’ salary, often at the Major League Baseball minimum, now $535,000 — obviously not too shabby. But in the context of baseball economics it is mere pennies. The best-paid player in baseball, the Dodgers’ Clayton Kershaw, earns $35.6 million a year, and some believe Bryce Harper, when he becomes a free agent in 2018, could sign a multi-year contract worth $400 million.

In the world of baseball, as in most sports, young talent is always more valuable to the team than old. This is not just because young players’ skills and athleticism haven’t atrophied yet; it’s because they’re cheap. A player doesn’t reach true free agency until he has spent six years in the majors, and earns only the league minimum until his third season, when he reaches “arbitration,” a process of generating small, graduated raises that is infamously management-friendly. A team — and this is key — also has total control over a player for the first six seasons of his career; if you draft a guy or sign him from another country, you own the rights to his services for his first six full seasons. After that, he can, for the first time, at last test the free market for his skills. Which means that any team — but especially those that can’t afford to compete for big-ticket free agents — has an incentive to get whatever value out of its young players it can in those first six years. No matter the long-term consequences.

The result is a system where ball clubs are encouraged — are essentially commanded — to squeeze every last bit of life out of their young pitchers, until their arms are ruined … conveniently, right around the time they’re due to hit the open market. Recently, Martinez — remember, he was the only pitcher whose arm hasn’t been hurt yet — signed a long-term contract in which the team bought out his arbitration period and some of the years he would’ve been eligible to sign elsewhere as a free agent. But it, too, was a below-market deal, for only $11.5 million a year — less than half of what outfielder Josh Hamilton made in both 2016 and 2017, despite having not played a single game either season.

Ask Syndergaard about this. After last season, the Mets essentially planned the future of their entire franchise around him. But they offered him only a $605,500 one-year contract heading into the 2017 season; according to most calculations, he had been worth about $45 million the previous year. Syndergaard was so frustrated by the offer — the minimum required — that he refused to sign, but that was just a symbolic gesture. He had no choice but to play for the Mets: The Mets have the rights to Syndergaard through the 2021 season. Who knows what will happen between now and then? Maybe Syndergaard will have had Tommy John surgery? Maybe his arm will wait to truly explode in 2020? Syndergaard, had he been allowed to hit the open market before the season, could have conceivably been paid $25 million a year. But he wasn’t allowed. And now his entire career is on the brink, five years before he can cash in.

But that’s the life of a pitcher. Be cheap, throw hard, and unload every bullet before you start getting expensive. Teams have finally decided that since they can’t figure out how to keep pitchers healthy — and they can’t, as chronicled memorably in writer Jeff Passan’s 2016 book The Arm — they would rather not bother themselves with it. They’ll just run them ragged, pay them little, ruin those elbows, and happily move along. Noah Syndergaard blew out his arm; Matt Harvey blew out his; when pushed to reach these velocities, everybody ultimately does. Who’s to blame? Maybe you just blame the suckers who are rube enough to take such a shit job as “pitcher” in the first place. Pitching used to be the best way to make money in sports; it might now be the worst, and it is entirely by design. Mamas, don’t let your babies grow up to be pitchers.

*This article appears in the May 1, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.