The House of Representatives last week passed draconian cuts to health-care coverage by starting on their right flank, and then pressuring vulnerable swing-district members one by one until they acquired a majority. The Senate is attempting to duplicate the strategy. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has entrusted the formulation of his chamber’s health-care bill to a 13-member working group that includes his most extreme members, like Ted Cruz and Mike Lee, while excluding those most likely to defect. Republicans who have expressed concern about cutting Medicaid, like Susan Collins, Lisa Murkowski, and Shelly Moore Capito, are locked out, as are Republicans who might lose seats in a midterm wave (Jeff Flake and Dean Heller). Most pointedly, McConnell has frozen out his party’s most vigorous critic of the House plan: Louisiana senator Bill Cassidy.

There is a template for the Republican moderate in the last quarter-century. They mutter nervously about their party’s direction, and offer their public prayers for a bipartisan solution, but ultimately fold under pressure from their leadership (or, less frequently, leave their party altogether, like Jim Jeffords or Arlen Specter, who switched parties). Cassidy is unique in several respects. He does not come from a blue or purple state, and has no electoral motivation to buck the party line, or to posture as a holdout. Before 2017 he did not have any public identity as a moderate. Most important, he has dissented from the Republican line on health care in ways that go well beyond the vague inferences of his colleagues and undercut the foundations of their argument. Cassidy’s dissent has gone much farther than many people realize.

Obamacare’s coverage gains should be expanded, not rolled back. The conservative movement fervently opposes on principle any expansion of the welfare state. It has viewed Trump’s election as a rare chance to eliminate a social benefit that the government has already created, which is why the GOP has been willing to endure severe political pain in order to repeal Obamacare. In particular, Republicans argue that Americans have no right to medical coverage, and that having insurance does not make you any better off.

Cassidy has instead maintained that all Americans ought to have access to medical care. “There’s a widespread recognition that the federal government, Congress, has created the right for every American to have health care,” he said in March.

The Congressional Budget Office is helpful. Republicans have either dismissed or wildly distorted the Congressional Budget Office’s estimates of their plans — indeed, the House did not wait for CBO to analyze the most recent version of its bill before rushing ahead on a vote. When confronted with the agency’s studies, Republicans wave them away as biased and false.

Cassidy instead urges that its conclusions be taken seriously. “You have to have an umpire, even if the umpire occasionally gets it wrong, because otherwise you are only accepting analysis by people with motivations [to] define certain answers, and so I am very reluctant to disregard what the CBO score is.”

The Republican plan actually raises premiums. Republicans have boasted that the House plan reduces premiums. This is only true in one narrow, deeply misleading way. The Republican bill would drive older, sicker patients out of the market by making insurance unaffordable for them. The remaining customer base would be younger and healthier. As a result, they would pay, on average, lower premiums than the customer base pays in the current exchanges, because they would be buying insurance that covers less care.

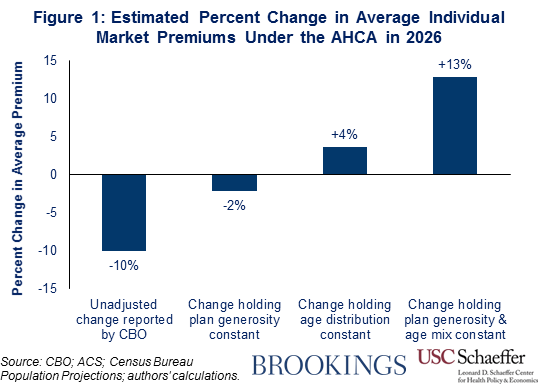

A paper by Brookings neatly displays how, if you look at what it would cost for a given person to buy a given level of insurance coverage, the GOP plan actually increases premiums by 13 percent:

The right’s approach has centered around making insurance skimpier, and targeting coverage at younger, healthier people who need less care. They market this idea with pleasant-sounding market euphemisms. Cassidy talks about these ideas the way most Americans do: They’re trying to give people terrible insurance. “I realized the way you lower premiums is that you have terrible coverage,” he told the American Hospital Association yesterday. Cassidy added, “The House plan was scored by the Congressional Budget Office as actually raising premiums.” Calling terrible insurance “terrible,” and admitting the Republican plan makes decent coverage more expensive — this is pure heresy.

Cutting taxes means cutting care. Republicans have sequenced health care before tax cuts because they want to repeal Obamacare’s taxes on rich investors. This strategy, insisted on by Paul Ryan, would use Obamacare repeal to grease the skids for lower taxes. Ryan’s health-care plan reduces taxes on the rich by nearly a trillion dollars, a sum that is offset by lower spending on health-care subsidies.

And while Republicans absurdly deny that their plan would take insurance away from anybody, it’s mathematically obvious that cutting health-care subsidies for the poor and middle class by a trillion dollars is going to result in about a trillion dollars less medical care for the poor and middle class.

Cassidy has come out squarely against using health-care reform to finance a tax cut. “I am a critic of the American Health Care Act,” he continued, to applause from the American Hospital Association yesterday. “I think it’s to set up tax reform and all the money used for coverage is instead going to be used to pay down the bill for tax reform.” When Jimmy Kimmel suggested last night, “I can think of a way to pay for it, is don’t give a huge tax cut to millionaires like me, and instead, leave it how it is. That’s my goal,” Cassidy (appearing on the program) replied, “Tell the American people to call their senators and endorse that concept.”

Donald Trump did not simply run on repeal. Republicans in general have made two promises to the American public. They have attacked Obamacare and promised to repeal it, and also promised to replace it with an alternative that would have lower premiums and deductibles. Given that Republicans oppose any method that would finance better insurance that has lower premiums and deductibles, these two promises turn out to be completely incompatible. Most Republicans have chosen to pretend they only promised repeal, and did not promise to replace Obamacare with better insurance.

Cassidy has emphasized the replace aspect over the repeal aspect. When the CBO found in March that the House plan would throw 24 million Americans off their insurance, Cassidy called it a betrayal of Trump’s commitment. “That’s not what President Trump promised,” Cassidy told CNN. “That’s not what Republicans ran on.” In his remarks to the American Hospital Association yesterday, Cassidy explained, “It’s not that [voters] wanted to get rid of Obamacare, they wanted something better,” he said.

++

Cassidy is neither a liberal nor an unqualified defender of Obamacare. He has criticized the status quo for its very real shortcomings — a lack of competition in rural markets, insufficient subsidies for modestly affluent customers whose incomes place them above the subsidy cutoff, and a clumsily designed individual mandate. Taken as a whole, though, Cassidy’s remarks point toward a wholly different direction on health care than his party’s leadership has indicated. Cassidy would construct a plan with different goals: fixing Obamacare rather than tearing it down, and prioritizing more coverage over lower taxes for the rich. And his approach would require a very different political coalition than the one constructed by Ryan and McConnell: Cassidy’s ideas would alienate right-wing Republicans and rely in part, perhaps even mostly, on Democrats.

Working on such a plan with Cassidy would present Democrats in Congress with a difficult choice. They would have to compromise at least some of their ideological objectives in order to make a deal with him. They would also have to surrender what is currently shaping up as their most potent attack and their best chance to retake the House in the midterms. (Either the passage of the cruel Republican plan, or the collapse of the exchanges, or both, could well create a Democratic-wave election.)

But for that scenario even to become a possibility, Cassidy will have to stop McConnell’s steamroller. The math at this point is very simple. Republicans hold 52 Senate seats. They need 50 votes (along with a tie-breaking vote by Vice-President Mike Pence) to pass some version of the House health-care plan, which is designed to be enacted through a budget-reconciliation measure that cannot be filibustered. Ryan hopes the Senate will pass some iteration of his plan within “a month or two.” And it will — unless three or more Republican senators oppose it.

The history of the Republican Party over the last generation — starting, roughly, with the Age of Newt — is a history of conservatives grinding the moderate wing into dust. If Cassidy is going to prevail, he will have to hold two or more of his wavering colleagues, and himself, in the face of what is sure to be unrelenting pressure from the White House and the conservative-movement apparatus. The only reason to think he might succeed, where most before him have failed, is that none of Cassidy’s predecessors have contradicted the party line so baldly and boldly.