One of the ways Donald Trump’s budget claims to balance the budget over a decade, without cutting defense or retirement spending, is to assume a $2 trillion increase in revenue through economic growth. This is the magic of the still-to-be-designed Trump tax cuts. But wait — if you recall, the magic of the Trump tax cuts is also supposed to pay for the Trump tax cuts. So the $2 trillion is a double-counting error.

Trump has promised to enact “the biggest tax cut in history.” Trump’s administration has insisted, however, that the largest tax cut in history will not reduce revenue, because it will unleash growth. That is itself a wildly fanciful assumption. But that assumption has already become a baseline of the administration’s budget math. Trump’s budget assumes the historically yuge tax cuts will not lose any revenue for this reason — the added growth it will supposedly generate will make up for all the lost revenue.

Here’s how the White House attempted to explain all of this.

But then the budget assumes $2 trillion in higher revenue from growth in order to achieve balance after ten years. So the $2 trillion from higher growth is a double-count. It pays for the Trump cuts, and then it pays again for balancing the budget. Or, alternatively, Trump could be assuming that his tax cuts will not only pay for themselves but generate $2 trillion in higher revenue. But Trump has not claimed his tax cuts will recoup more than 100 percent of their lost revenue, so it’s simply an embarrassing mistake.

It seems difficult to imagine how this administration could figure out how to design and pass a tax cut that could pay for itself when Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush failed to come anywhere close to doing so. If there is a group of economic minds with the special genius to accomplish this historically unprecedented feat, it is probably not the fiscal minds who just made a $2 trillion basic arithmetic error.

Update: Asked about this absurd mistake, Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin’s explanation does not inspire a great deal of confidence:

This is apparently the best defense they could come up with: Eh, we’ll fix it later. It’s only the budget for the federal government of the United States of America.

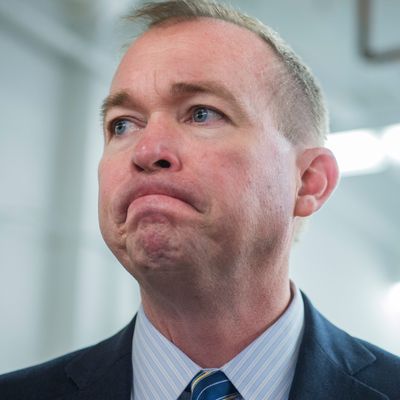

Meanwhile, Mulvaney tells reporters that the assumption was “reasonable” because… reasons:

I’m aware of the criticisms, and I would simply come back and say, look, there’s other places where we were probably overly conservative in our accounting. We stand by the numbers. We thought that the assumption that the tax reform would be deficit-neutral was the most reasonable of the three options that we had. We could either assume that our tax reform was deficit-neutral. We could assume it would reduce the deficit. We would assume it would add to the deficit. And given the fact that we’re this early in the process about dealing with tax reform, we thought that assuming that middle road was the best way to do it.