Right-wing critics of Obamacare have been predicting for years that the law would enter an actuarial “death spiral,” in which healthy customers flee and insurers raise rates to unsustainably high levels as only the most sick and expensive patients remain. The alleged death spiral has played a crucial role in Republicans’ rhetoric, undergirding their claim that the law is collapsing of its own accord. When President Trump repeatedly insists Obamacare is “collapsing,” “dead,” or “gone,” he is popularizing in vulgar form an analysis that people like Paul Ryan have been spreading for years.

The most obvious sleight of hand in this argument is that, even if it were true that the Obamacare exchanges were entering a death spiral and collapsing, it would hardly justify the Republican health-care bill. The exchanges account for a bit less than half the coverage gains in Obamacare. The rest of the newly insured come from expanded children’s health insurance and, especially, Medicaid.

Remember, Medicaid expansion is how Obamacare provides insurance to the poorest Americans (those with incomes up to 133 percent of the poverty level). The allegedly collapsing exchanges only insure people with incomes above that level. And the spine of the GOP plan is hundreds of billions of dollars in cuts to Medicaid. There’s not even a patina of an argument that Medicaid is collapsing. The supposed “death spiral” in the exchanges is the Republican pretext for cutting a completely different program.

In any case, the “death spiral” is a fiction. An S&P analysis last spring found that insurers in most markets had found a stable and profitable price point. The conclusions received some attention, but the guts of the analysis deserve a bit more attention. What S&P found was that health costs of people buying insurance on the exchanges have converged with health costs of people who get insurance through their employer.

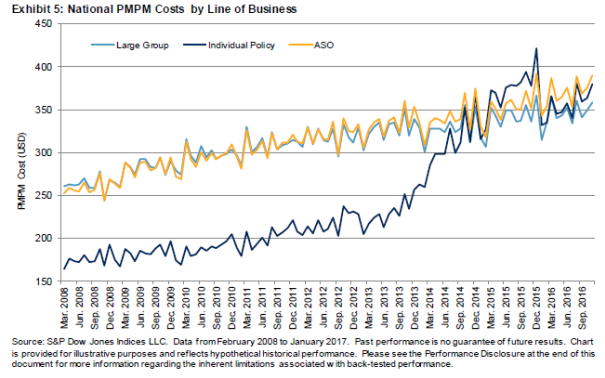

Look at the chart below from the report:

The dark blue line is the per-patient cost of people in the individual market. The light blue line is people in the employer market. Before Obamacare, individual insurance costs were much lower because insurers weeded out anybody who had a preexisting condition, and only sold insurance to people who were extremely healthy. Then, when Obamacare passed, the regulated exchanges enabled people with expensive medical needs to buy affordable individual insurance for the first time.

The costs of those patients ran well above the employer market in the first year or so it was available. That happened in part because many of the newly insured Americans had waited years for coverage and had a backlog of medical needs. That’s why the dark blue line shot up well ahead of the light blue line in 2014 and 2015. That trend is what a death spiral would look like — the dark blue line would keep rising well ahead of the light blue line. But that hasn’t happened. Since last year, the costs of patients in the individual market and patients in the employer market have converged.

So why are we reading all these stories about insurers pulling out of markets and premiums going way up? Oliver Wyman, an actuarial firm, examines the markets and concludes that at least two-thirds of the higher premiums next year are due to political uncertainty created by the Trump administration and Congress. The administration is threatening to withhold payments insurers are owed under the law, and also not to enforce the individual mandate. These deliberate efforts to subvert the exchanges are having their intended effect. But the underlying expected cost of insuring patients is low — without a government engaged in deliberate sabotage, the firm estimates premiums would only rise 5–8 percent, a very modest level by the historic standards of health insurance costs.

Obamacare can be improved, especially in rural markets where hospitals and doctors are spread far apart and competition has always been difficult to produce. But the threat to the exchanges is the same as the threat to Medicaid: not any inherent flaw in the operation of the programs, but a governing party that ideologically opposes the transfer of resources that is needed to make health care available to the poor and sick.