Karen Handel’s close-but-not-that-close win in Georgia’s sixth district, the fourth Republican victory in four special elections, has officially made the party’s failure to capture a House seat in 2017 a capital-T Thing. “Let’s be clear: something ain’t working for Democrats, party insiders privately tell us,” reports Politico Playbook. Representative Ro Khanna, sounding like an upset fan calling into a sports talk radio show, called for the party to “fire its consultants” and replace them with three of his favorite opinion journalists. “Deep down [Democrats] know they needed – and still need – a win in a high-profile race in which the fight was between Trump/Republicans and Pelosi/Democrats,” writes Chris Cillizza. “There are no moral victories in politics. No matter what the losing side says — and they always say this — the only thing that really matters when it comes to special elections is the ‘W’ and the ‘L.’”

It’s certainly true that Jon Ossoff’s underperformance of the polls (he was nearly tied in the polling average, and is losing by almost 4 points) should incrementally adjust one’s view of the Democrats’ prospects. But the reason the party has lost all four special elections is glaringly simple. It is not some deep and fatal malady afflicting its messaging, platform, consultants, or ad spending allocation methods. Republicans have won the special elections because they’ve all been held in heavily Republican districts.

The special elections exist because Donald Trump appointed Republicans in Congress to his administration, carefully selecting ones whose vacancy would not give Democrats a potential opening. It feels like Democrats somehow can’t win, but that is entirely because every contest has been held on heavily Republican turf.

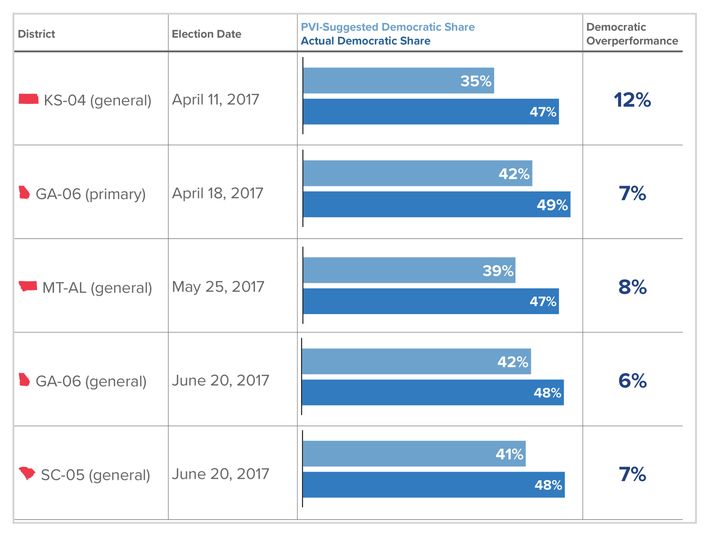

The overall measure of Democrats’ standing at the moment is not whether they have won, but how they have performed relative to the partisan composition of the districts in which they are running. That gauge remains quite positive. As Dave Wasserman points out, in the four special elections, they have overperformed the partisan baseline in their districts by an average of 8 percentage points:

If that performance holds up in the midterm elections, it would be enough to make Democrats solid favorites to win a House majority. (The undemocratic makeup of the House map means Democrats need to increase their votes by some 6–7 percent in order to gain a majority. Of course, since the midterms don’t take place for more than a year, things could change in either direction. President Trump might change course and pass a popular domestic initiative, or benefit from a foreign crisis, or some kind of racialized conflict provoked by his draconian law-enforcement policies.

On the other hand, Trump’s standing could well deteriorate between now and then, given that the only crises he has faced so far are ones he’s created, and his managerial prowess has not exactly inspired confidence. In 2009, Democrats not only won four straight special elections to replace departing House Democrats, they also flipped a House seats from a retiring Republican. Imagine how despondent Democrats would feel if they lost a Democratic seat with Trump in office. At the time, Democrats saw the victory as evidence that they were safe from a midterm wave. “This election represents a double blow for national Republicans and their hopes of translating this summer’s ‘tea party’ energy into victories at the ballot box,” crowed the Democrats’ House campaign chairman. As it turned out, the situation deteriorated pretty badly over the next year.

So what accounts for the deep gloom overtaking Democrats? There are the atmospherics of repeatedly losing, which overpower any circumstantial explanation. There is also a long-standing party division over tactics, which gives all sides an incentive to play up the direness of defeat in order to emphasize their own customary remedies. (“My strategy will make our party stronger, but we’re doing fine anyway” is an argument nobody in history has ever made.) And then there is the psychology of surprise. A few months ago, a 4-point Ossoff defeat would have met expectations. After a frenzied nationalized race, it comes as a massive blow, which requires explanations large enough to bear the weight of the trauma it has inflicted upon Democrats.

Matthew Ygelsias’s take on Ossoff’s defeat urges Democrats to change course, citing, among other models, “Jeremy Corbyn’s surprisingly strong showing.” Corbyn, of course, lost his race, just as Ossoff did. And Corbyn, unlike Ossoff, ran nationally (rather than in a heavily conservative district) and faced a deeply discredited incumbent. An average Labour nominee not encumbered by Corbyn’s left-wing baggage would probably have won a clear victory. But since Corbyn did lose by less than he had been expected to a few weeks before, momentum transmuted his narrow defeat into a galvanizing victory, just as it transmuted Ossoff’s narrow defeat into a debacle.

The final reason for the overreaction is that everybody has priced irrationality into the system. That is, even people who know perfectly well that a swing of a few points one way or another in a single race tells very little about national conditions expect other people to overreact. It is quite possible that Handel’s victory will encourage nervous Republicans to continue holding the line for Trump’s unpopular agenda. But, to the extent the race increases the odds of Congress passing a health-care bill that polls below 20 percent, it would raise, not lower, the chance that Democrats make midterm gains. (Not that many Democrats would take that trade-off.) The irrational-response factor helps rather than hinders Democrats.

But perhaps the better response is to take irrationality for granted, and start to act … rational?