The Republican Party’s primary objections to Obamacare were twofold: The law transferred resources from rich to poor, and was passed by a Democratic president.

But the GOP declined to prosecute its case against the Affordable Care Act on these grounds. Instead, Republicans focused their fire on the ACA’s most unpopular provision — the one so politically poisonous, even Barack Obama resisted endorsing it on the campaign trail.

The individual mandate allowed Republicans to fight the ACA with conservative economic orthodoxy — without getting into a losing argument about the wealthy’s divine right to every cent of their passive income. By requiring every American to buy insurance or face a financial penalty, the individual mandate achieved a malevolent synthesis of nanny-state overreach and crony capitalism. Or so conservatives could reasonably argue (in between bad-faith scaremongering about how the first African-American president was trying to take away white people’s Medicare, to fund another handout for the undeserving poor).

The mandate made it easy for Republicans to frame the most egalitarian piece of lawmaking in a generation as a bid to sacrifice the liberty of the many to line the pockets of a few big insurers. And yet, Obama had no choice but to insist on the measure, because his law would fall apart without it.

Universal health care and a for-profit insurance industry can be reconciled. Plenty of countries feature both. The trick is forcing insurers to offer affordable coverage to everyone (including the very sick) — while forcing everyone to purchase insurance (including the young and healthy). That way, insurers can afford to absorb the losses inherent to covering known liabilities.

But without a coercive mechanism, such a system falls apart. The old and sick flood the insurance market, while the young and healthy stay on the sidelines. This leads insurers to adopt higher premiums, which chases even more young people out of the market, which creates a need for even higher premiums — sending the whole structure into a death spiral.

The specter of such death spirals has figured prominently in the 2017 GOP’s case against the ACA. When unable to muster a positive case for their health-care bills, the party has fallen back on the claim that keeping things as is isn’t an option, because Obamacare is collapsing.

There is a sliver of truth to the GOP’s complaint. While the ACA’s marketplaces are broadly stable, many exchanges in rural counties have ceased to function. But to the extent that Obamacare’s marketplaces are failing, they are doing so because of too little government coercion, not too much: The problem is that law’s mandate is far weaker than those enforced by other countries with similar systems. Switzerland provides universal health care through for-profit insurers — but it will also throw people in jail if they refuse to buy a plan.

This has put congressional Republicans in a difficult position: They have promised to eliminate the unpopular, coercive element of Obamacare — and to fix a problem with the law that can only be solved through even more heavy-handed government coercion.

Last week, the Senate released a health-care bill that solved this conundrum by pretending it didn’t exist: The Better Care Reconciliation Act preserves the structure of the Obamacare marketplaces, reduces subsidies, and abolishes the individual mandate — while replacing it with nothing.

Even the bill’s lonely champions know that this is not an option.

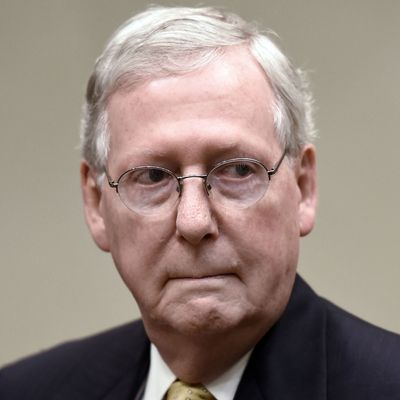

And so, on Monday, McConnell unveiled the GOP’s small government approach to forcing Americans to buy something they don’t want. As Vox reports:

The Senate health care bill will aim to penalize Americans who have breaks in insurance coverage, an updated draft released Monday shows.

The new bill includes a six-month waiting period for those who want to purchase individual market coverage but have had a more than two-month break in coverage at some point in the past year

Under this rule, if you miss a payment on your insurance, go without coverage for an extended period of time — and then develop a serious illness — you will have no means of obtaining coverage on the individual market for six months. Which is to say: Instead of coercing Americans into buying insurance through a small financial penalty, the GOP would do so by locking some cancer patients out of access to insurance for a potentially fatal amount of time.

Before Monday’s announcement, McConnell’s bill had already attracted widespread opposition. Hospitals, physicians’ groups, disability advocates, the AARP, and many other health-care stakeholders had lambasted the plan. Five Republican senators had declared their opposition to the bill as written, countless others had expressed grave concerns, and virtually none had offered an enthusiastic endorsement of the legislation. Since the bill’s unveiling, President Trump’s job approval rating has fallen four points, according to Gallup.

From one angle, this isn’t too surprising. The Senate bill is broadly similar to the House’s — and only 16 percent of Americans see Paul Ryan’s scheme to finance a large tax cut for the rich by throwing poor people off of Medicaid in a good light.

But it’s still a bit remarkable that the Senate generated an Obamacare alternative this unpopular, even as it gifted itself the privilege of omitting any replacement for the current law’s most-despised necessity.

Thus far, Republican opposition to McConnell’s bill has been split between moderates who find it too cruel, and conservatives who find it ideologically impure. The six-month waiting period might allow these dissidents to make common cause. And yet, the odious provision — or something like it — is required to prevent the bill from gutting the individual market. On Monday, the Congressional Budget Office found that the the absence of a mandate in the initial bill would help increase the ranks of the uninsured by 15 million next year.

Making matters even more difficult for McConnell, any alternative to the individual mandate could also face opposition from the Senate’s parliamentarian: The GOP is trying to execute Obamacare repeal through reconciliation, a process that allows bills to be passed by a simple majority vote in the Senate — so long as the legislation deals strictly with budgetary matters. It is hard to see how new rules about who is and is not allowed to buy insurance at a given moment in time would meet that requirement.

All that said, the CBO’s largely grim report contained one bit of good news for the GOP: The budget office argued that the suddenly smaller nongroup insurance marketplace would be stable – subsidies to consumers and insurers would be enough to prop up the more austere exchanges, even without a mandate. So, Republicans may actually be able to go without any coercive mechanism – provided they’re willing to accept a double-digit coverage loss as the cost of that evasion.