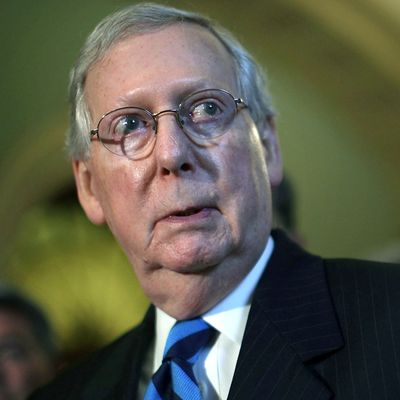

After the sudden opposition of Senators Mike Lee and Jerry Moran all but killed plans to move ahead with a vote on the revised version of the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017, Mitch McConnell quickly announced his next step would be to hold a vote on the “straight Obamacare repeal bill” that Obama vetoed last year. This is precisely what President Trump demanded when he was blindsided by the defections while holding a dinner to talk health-care strategy with other Republican senators:

This movement back to the strategy that was discarded by the GOP before Trump was inaugurated reflects conservative complaints that all of the “replacement” language Congress has been kicking around insufficiently repeals the Affordable Care Act. So, in a way, McConnell is saying to the White House and the dominant wing of his party: Okay, we’ll try it your way.

The prevailing sentiment is that while a “straight repeal” bill might bring restive conservatives back into line (Mike Lee, for example, indicated he’d happily support a motion to proceed to that kind of vote), enough Senate moderates will object to its baleful consequences to kill it. In fact, since the procedure for allowing a repeal vote requires a period of wide-open amendments, the Senate could wind up with a bill that’s even less unifying than BCRA.

As Matt Yglesias reminds us, a straight repeal vote seems scary because so many Republican senators voted for the 2015 version — 48 of them, to be exact (Susan Collins voted against it, and John Kennedy, Todd Young and Luther Strange were not in the Senate yet). Conservative activists and “base” voters already inclined to view moderates as RINO sellouts will be unmoved by the rationalization that the 2015 vote was symbolic given the certainty of an Obama veto.

But senators can rightly argue they did not have a full CBO assessment of a straight repeal bill when they voted for it in 2015. Now they do: In January of this year, at the request of Senate Democrats, CBO scored the 2015 bill and determined that it would reduce health-care coverage by 32 million individuals and nearly double premiums in the individual market. Yes, these estimates were based on a bill that, unlike BCRA, did not touch Obamacare regulations. But it also didn’t include the Medicaid per capita cap that strongly drove down coverage numbers in the House and Senate versions of Trumpcare. If McConnell or Senate amendments modify the 2015 bill to make it more appealing to this or that faction of Republicans, then the precedent established by voting for the original will become meaningless.

Additionally, there are at least nine Republican senators on record in 2017 as opposing an Obamacare repeal without a replacement being ready. So flip-flopping on that more recent position could seem more hypocritical than reversing a vote for a 2015 repeal bill.

Today, three more GOP senators — Rob Portman, Shelley Moore Capito and Lisa Murkowski — have already signaled they are not inclined to vote for a simple repeal. With Collins assumed to be opposed, that’s enough to sink it.

If a “straight repeal” bill is almost certain to go down to defeat, why is McConnell going in that direction? Most likely he wants to preempt any future conservative argument that he never intended to repeal Obamacare fully, and didn’t even try it. And in particular, he wants to deflect any fire coming from the White House, which has been promoting the revived repeal-and-delay strategy in recent days.

McConnell is also giving conservatives a shillelagh with which to beat Republican moderates who fail to go along with repeal, and perhaps even to mount primary challenges against them in 2018 or beyond. He understands that, like every GOP congressional leader, he holds his gavel at the sufferance of the right. After the Obamacare-repeal legislation fails due to the perfidy of the RINOs, McConnell can turn to tax and budget legislation and let the health-care mess simmer on a back burner until pressure mounts for a bipartisan fix of Obamacare.