To this day, Republicans haven’t forgiven Chief Justice John Roberts for casting the deciding vote that upheld the core of the Affordable Care Act. But along with his tie-breaking vote in the 2012 decision, Roberts also did something conservatives give him far less credit for, and he even convinced two of his more liberal colleagues to join him. He dealt a crippling blow to Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion, declaring that the requirement was essentially extortion: Agree to expand health-care coverage or lose all of your existing Medicaid funding. This, Roberts wrote, was akin to “a gun to the head” of the states, and thus unconstitutional.

Blocking that kind of unlawful coercion is federalism in action, which conservatives have fought long and hard to defend as a local check against federal overreach. And now that Donald Trump is running the federal government, it’s a principle that liberals and progressives are embracing with open arms, as Democratic-leaning states and localities mobilize to shield themselves from federal policies they consider retrograde or just plain damaging to their residents and interests. Hand over undocumented immigrants to Trump’s deportation machine? Perish the thought. Let the chief executive faithlessly sabotage the health-insurance market in an otherwise liberal bastion? Over our dead bodies. Or how about Jeff Sessions’s intended crackdown on local marijuana laws? Get out of town.

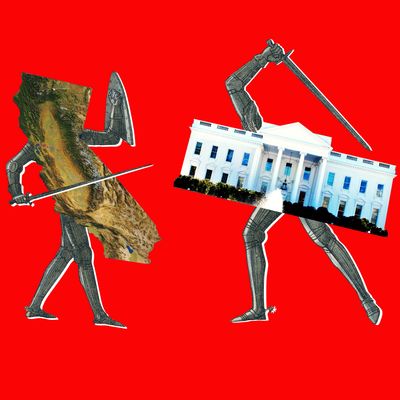

“Progressive federalism” is not a phrase you hear often, but the Trump era may have prompted a liberal awakening to the benefits of local pushback against centralized executive fiat. When the president announced his ill-begotten travel ban a week after he took office, it was up to states like Washington and Minnesota to score the first major victory against the executive order’s implementation. And so it’s been with other hotly contested legal battles — over sanctuary cities, clean air, the payment of certain subsidies under Obamacare. It has fallen to Democratic attorneys general and municipal leaders to be standard-bearers for the legal resistance against Trump, who otherwise seems committed to trampling on states’ rights, conservative principles be damned.

For Heather Gerken, the new dean of Yale Law School and one of the leading scholars in support of progressive federalism, Republican control of Congress and the presidency has given new urgency to her work. In the aftermath of the election, she co-authored a user’s guide in the journal Democracy on how localities can best harness the power of federalism to serve progressive ends. That’s not to say Democratic enclaves will necessarily carry this flag for the long haul. In an interview, she told me that people on both sides of the political spectrum tend to opportunistically wield federalism for their partisan ends — and not because of some high-minded constitutional commitment. “Both sides are fair-weather federalists. Both sides use it instrumentally to achieve their goals,” she said.

The leaders of the liberal resistance, naturally, won’t just cop to favoring federalism because it now suits them. During a recent press conference to announce a new lawsuit challenging Sessions’s war against jurisdictions that won’t turn over undocumented immigrants to the feds, Xavier Becerra, California’s attorney general, suggested his effort wasn’t about opposing Trump, but rather about standing up for our founding document. “I don’t see this as a fight against the federal government,” Becerra said, according to the Recorder, a legal publication. “We’re fighting to protect the Constitution.”

That’s the kind of lofty and legalistic talking point that Republicans have elevated to an art form. For example, Becerra’s counterpart in Texas, Ken Paxton, has insisted time and again that the scores of lawsuits his office felt compelled to file against President Obama were all about the rule of law and preventing federal encroachment in local affairs. “To protect civil liberties and prevent the concentration of power, the Constitution divides authority through the separation of powers and federalism,” Paxton wrote in a recent letter defending his decision to threaten more litigation over an Obama-era program aimed at protecting young undocumented immigrants who were brought to the U.S. as children. If Texas really cared about federalism, it should’ve gone after the federal program that helps these kids years ago.

Now that the shoe is on the other foot, Democrats are the ones relying on similar litigation tactics and conservative precedents to oppose Trump. And they’ve won some significant victories so far, which in turn have had the effect of slightly moderating the administration’s stance on some issues. In April, a federal judge in San Francisco admonished the Department of Justice that it can’t just threaten to strip funding from cities and counties simply because they refuse to do the government’s bidding on immigration. And he did so borrowing from Chief Justice Roberts’s language in the first Obamacare challenge before the Supreme Court: “The threat is unconstitutionally coercive,” wrote U.S. District Judge William Orrick about Trump’s executive order against immigrant-friendly sanctuary cities.

More dramatic still is what’s been happening in the second most powerful court in the country, the federal appeals court in Washington, where the Trump administration has been waging a fierce regulatory battle with New York’s Eric Schneiderman and other state attorneys general who insist that their states have skin in the game of how the federal government should enforce its own laws. In back-to-back decisions earlier this month, judges in that court recognized that these states should be able to intervene in cases where Trump, if left to his own devices, could simply decide that ozone pollution standards don’t matter, or stop making millions in cost-sharing payments to insurers that make coverage affordable to poor Obamacare beneficiaries.

In these court confrontations, tellingly, lies a key difference in how progressives and conservatives employ federalism. For conservatives, it’s all about stopping executive policy they don’t like: Texas alone spearheaded efforts to invalidate federal rules and directives aimed at protecting transgender students and patients, workers considering joining a union, and the undocumented parents of American citizens and permanent residents — all in the name of upholding the Constitution and laws and their state budgets and businesses. Progressives, on the other hand, really like some of these policies and have jumped in the fray to save them from non-enforcement or outright repeal by the Trump administration. And in the face of new actions by Trump’s team, their strategy has been to play offense, as in the bid by “sanctuary” states and localities to get the federal government to leave them alone on immigration.

These interventions have emboldened the Democratic base and maybe even contributed to the political aspirations of attorneys general and other local politicians. Federalism is now a tool to #resist. But is there a principled way for progressives to seize the moment and learn to love federalism for federalism’s sake, rather than just as a means to score political points against Trump or salvage a policy they favor?

Writing in National Review, Ilya Somin, a George Mason University law professor and longtime libertarian scholar of federalism, expressed hope that the Trump era could well be the time to “make federalism great again” for both progressives and conservatives — a moment for politicos and legal thinkers from both sides to find common ground and form a “new bipartisan and cross-ideological appreciation for limits on federal power.”

Yale Law’s Gerken, for her part, is skeptical that one can make a bright-line rule for federalism, but she says that there are issues, such as national security and the enforcement of federal civil-rights laws, that everyone should agree belong in the realm of the national government vis-à-vis the states. “I’ve never met a [federalist who says] that a state should control our nuclear arsenal,” she says. “There are always things no matter what side you’re on that you believe should be centralized. And there are almost always things that you think should be decentralized. The real question is, how much weight do you put on the scale for the values of federalism, and what you think federalism can achieve, given your goals?”