Earlier this year, Senator Bill Cassidy had claimed a role as his party’s primary heretic on health care. The Louisiana Republican slaughtered all manner of party sacred cows, culminating in an emotional appearance with Jimmy Kimmel, where he promised to safeguard health care for the sick and vulnerable. What happened next was depressingly familiar. Cassidy stopped criticizing his team and got onboard with their plan, ceasing his heresies and voting reliably for the various, doomed iterations of repeal and replace that came up through the summer. This was a familiar story of a dissident in a polarized Congress yanked back into line by his leadership.

What happened after that is the unusual part. Having surrendered his independence, Cassidy did not merely settle for the quiet life of an auto-voting partisan. He has transformed himself yet again, this time into a tireless crusader for repeal. While even many of the staunchest right-wingers in Congress have been willing to let the Obamacare repeal crusade die, Cassidy has thrown himself almost single-handedly into its revival.

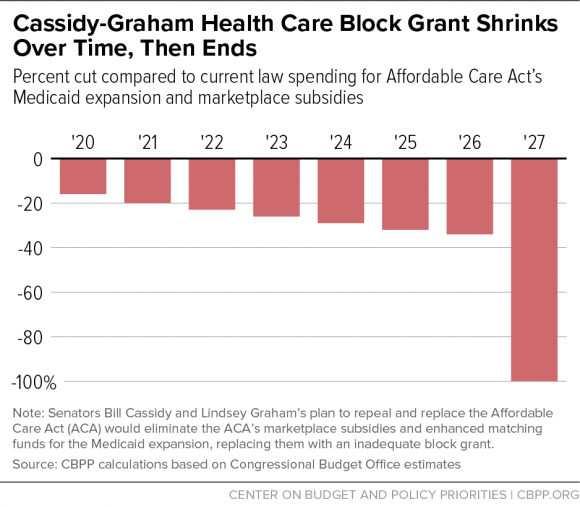

Cassidy has parted ways with his original co-sponsor, moderate Maine senator Susan Collins, with whom he hoped to build a bipartisan coalition, and is now partnering with South Carolina conservative Lindsey Graham. (The latter is now pleading with Breitbart to pressure the Republican leadership for a vote.) Cassidy-Graham is a plan to cut health-care subsidies — both Medicaid and tax credits for people on the individual market — by progressively deeper levels, up to one-third lower after ten years, after which point funding would end entirely unless reauthorized:

It would also allow states to weaken protections for people with preexisting conditions, giving insurers the freedom and incentive to segment their products, so that they charge less to healthier customers and much more to sicker ones.

If the repeal-and-replace fiasco has driven home any lessons, it is that there is no magic solution to the health-care-finance problem awaiting discovery. If you want to make health care affordable to people who are sick and poor, it has to be paid for by people who aren’t. Throwing the problem over to the states, and pretending those politicians can invent a solution that politicians in Washington could not, doesn’t make the trade-off disappear. You can make any paeans you want to the genius of state government, but there’s a reason no states other than Massachusetts (which got a federal grant) ever cracked the universal-coverage problem. Less money means less coverage. Letting healthy people buy plans that don’t cover expensive conditions means people who do have expensive conditions pay a lot more.

What’s so odd is that Cassidy used to recognize this. Should Washington slash the amount of resources for making insurance affordable and throw the problem over to the states? Cassidy didn’t used to think so. “There’s a widespread recognition that the federal government, Congress, has created the right for every American to have health care,” he said in March. What about the Republican proposal to let insurers sell skimpy coverage for less money? Cassidy used to avoid the usual euphemisms and admit this was what most people called “terrible coverage.” (“I realized the way you lower premiums is that you have terrible coverage,” he told the American Hospital Association in May.)

The old Cassidy believed health care had to be written with some care, working through committees. (“I think anytime you bypass regular order in the Senate, the committees of jurisdiction, it’s a little bit problematic.”) The new Cassidy wants to rush his bill into law through budget reconciliation, avoiding hearings and compressing debate.

And the old Cassidy believed the Congressional Budget Office had an important role in studying legislation: “You have to have an umpire, even if the umpire occasionally gets it wrong, because otherwise you are only accepting analysis by people with motivations [to] define certain answers, and so I am very reluctant to disregard what the CBO score is,” he said in March. The new Cassidy insists the CBO should be ignored: “I just don’t care about the coverage numbers, because their methodology has proven to be wrong,” he now declares. “And ours, frankly, empirically, is correct.”

Whether the exact size of the coverage losses from a piece of legislation as vague as Cassidy’s can be calculated is a fair question. But there’s no doubt cutting the federal subsidy by a third will make health care unaffordable to a huge number of Americans. Cassidy’s plan is to rush his bill into law as quickly as possible, before stakeholders or outside analysts can get a proper handle on its enormous effects.

There is no generally circulating theory to explain Cassidy’s reversal. Behavior that can be adequately explained by ignorance usually does not require venality. Few politicians are public policy experts. Cassidy used to believe there was no magic way around the problem of financing health care for people who can’t afford it, a finding that inconveniently put him at odds with his party’s long-standing promises. Now he has probably found a right-wing health care “expert” who has “explained” to him that such a solution actually exists, if you simply transform concepts like state flexibility and innovation into a magic elixir. Whatever the explanation, the brief moral awakening of Bill Cassidy has come to a screeching halt.