Back in August, sitting on the Gracie Mansion porch, I asked Mayor Bill de Blasio why, after all he had accomplished in his first term, his poll numbers were so middling. He smiled and didn’t hesitate. “You will be able to judge what people think of me on November 7th,” he said. “Look at Bloomberg and look at a lot of others: A lot of turbulence along the way and Election Day proved in some cases to be very different. So let’s withhold our final assessment till that point.”

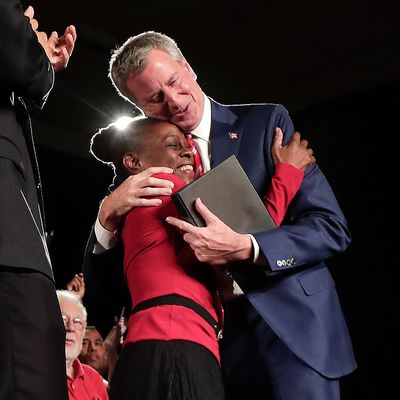

The results are now official. De Blasio demolished Republican candidate Nicole Malliotakis by almost 40 points, with more than 1 million New Yorkers voting, to become the first city Democrat to win a second term since Ed Koch in 1985. There is no way around it. Give the man his due. If you go by yesterday’s numbers, New York absolutely loves Bill de Blasio.

Whether fellow politicians, particularly in Albany, share that feeling is a very different question, one that will determine how much he can accomplish in the next four years. The most immediate indicator of how much weight the mayor’s romp carries will come in the insider race to choose the next speaker of the City Council. Typically the Bronx and Queens Democratic county organizations team up and select the council leader, but four years ago they were outflanked by de Blasio, who joined with Brooklyn’s boss and newly elected council progressives to help install Melissa Mark-Viverito. This time the race is wide open and the field crowded, so the mayor’s backing could be decisive. De Blasio has kept his preferences quiet; at times there have been hints he is leaning toward Donovan Richards Jr., a young African-American councilmember from southern Queens. Yet the leaders in the contest seem to be two Manhattan members, Corey Johnson and Mark Levine.

Getting his pick of speaker should make it easier for de Blasio to advance his legislative agenda. With the emphasis on should, because the mayor is now a term-limited lame duck, and a bunch of ambitious fellow Democrats will now be angling to run for citywide office in 2021. One key way for them to raise their profiles will be by fighting with the mayor, usually from the left. City-council votes on land use — necessary to advance the mayor’s affordable housing and homelessness plans — will become heated, as will proposals to more tightly regulate the NYPD.

“The quietness before the election is about to be reversed,” says Mitchell Moss, a professor of urban policy and planning at NYU. “The term-limits law has backfired — no incumbent wants to risk giving up a seat, so we have no competition for eight years. Those pent-up political tensions will erupt starting with the speaker’s race, where geography, gender, and race will combine to create friction. De Blasio is going to have a tough time defining the next four years, because everyone else will be trying to define themselves — not just councilmembers, but people like Scott Stringer and Tish James who want his job.”

Because the 2017 mayoral race was never competitive, de Blasio had the luxury of playing it safe when it came to laying out what he wants to do in the next four years. He was actually more specific than was probably required. The mayor has added 100,000 units to his affordable housing goal; he has begun an expansion of prekindergarten to 3-year-olds; he has said he wants to force landlords to retrofit old buildings to make them greener; and he has proposed raising taxes on the rich to pay for subway repairs. Most of those are worthwhile ideas; none of them are particularly new ground. They should also present relatively easy wins compared to three other seemingly intractable problems: reducing homelessness, increasing educational gains for the city’s poorest students, and creating a more humane jail system. “He has promised that he is going to discontinue the use of cluster sites for the homeless and bring people to neighborhoods where they came from, and he’s promised to close Rikers Island,” says Joseph Viteritti, a Hunter College professor and author of The Pragmatist: Bill de Blasio’s Quest to Save the Soul of New York. “It is going to be controversial and expensive to pull both of those off. He’s also probably going to need to revisit his Renewal Schools strategy.” The mayor has spent $580 million so far, with meager results; part of a new solution could well include a new schools commissioner — Carmen Fariña took the job only reluctantly four years ago.

De Blasio’s ability to fund that program — while also going on a civil-service hiring spree across just about every city agency — is indicative of probably the biggest factor underlying his big victory: the city is not just safer but flush with cash. Steady national economic growth, the global trend toward re-urbanization, and the tailwinds of the Bloomberg years have swollen municipal revenues. The mayor’s first-term success in converting progressive values into policy was made significantly easier by the city’s surpluses. Yet there are financial warning signs. “The city’s tax revenue growth is not keeping pace with the city expense budget growth,” says Kathy Wylde, president of the Partnership for New York City, a major business group. “When things are going well, you can get away with a lot that you can’t when things are going badly.” The Republican tax plan now being debated in Washington could cost the city billions. “Our fear is that the reversal of state and local taxes and the general federal withdrawal of financial support for infrastructure and health care is going to threaten New York,” Wylde says. “The question is, if we start getting headwinds, how will de Blasio respond?”

In 2013 de Blasio’s campaign focus was closing the city’s income-inequality gap. His victory speech last night was a variation on that theme: making New York the fairest city of them all. The local issues and values he emphasized in that cause — including equal pay for women, support for broad immigration, and tax hikes for the wealthy — all have national resonance, and de Blasio wasn’t shy about making the connection clear. “Tonight New York City sends a message to the White House: You can’t take on New York values and win, Mr. President,” he said, to loud cheers. “Your hometown will fight back.” The mayor stumbled when he tried to become a national player in his first term, but he sees his resounding win, on a night when Democrats reasserted themselves across the country, as an invitation back into the conversation in 2018. Closer to home, he’ll try to leverage his landslide to push Andrew Cuomo to the left as the governor ramps up his own reelection bid. That strategy has bought de Blasio plenty of headaches in the past. This time he’s hoping it yields more money to repair New York’s crumbling subways.

The city has, fortunately, gone four years without suffering a major natural disaster, massive terrorist attack, or drastic economic downturn. Extending the streak through 2021 would be good for everyone. But the laws of political physics almost demand that Bill de Blasio is in for a true test, one that will be a great deal more stressful than the electoral challenge he just passed. “I don’t think anyone walks in the door fully formed to be mayor of New York City. You have to learn on the job,” he told me two months ago. “The good news about that from my perspective is the more you do it the more it makes sense.” That’s a good thing, because yesterday’s reelection landslide was a formality, and the goodwill it generated will likely prove to be temporary.