Since 1990, the Temporary Protected Status program has shielded foreign nationals from deportation if the executive branch determines that they’re likely to find unsafe conditions — such as from a natural disaster or conflict — if they return home. For many years, renewing TPS status was seen as an obscure bureaucratic matter. About 320,000 people now benefit from the program.

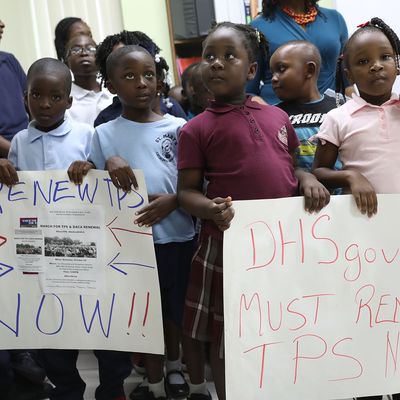

However, a program that lets people from troubled nations stay in the U.S. indefinitely does not jibe with the Trump administration’s approach to immigration policy. After announcing it would not renew the temporary status of 2,500 Nicaraguans earlier this month, on Monday acting Homeland Security secretary Elaine Duke said 60,000 Haitians should prepare to exit the U.S. within the next 18 months.

The Haitians were given protected status after an earthquake ravaged the country in 2010. Department of Homeland Security officials noted that the program was always meant to be temporary, and said the “extraordinary conditions” that led to the Haitians being allowed to remain in the U.S. “no longer exist.”

“Since the 2010 earthquake, the number of displaced people in Haiti has decreased by 97 percent,” said Duke. “Significant steps have been taken to improve the stability and quality of life for Haitian citizens, and Haiti is able to safely receive traditional levels of returned citizens.”

The administration had faced bipartisan calls to renew the Haitians’ provisional residency. In a Miami Herald op-ed, Senator Marco Rubio said those “sent home will face dire conditions, including lack of housing, inadequate health services and low prospects for employment … Failure to renew the TPS designation will weaken Haiti’s economy and impede its ability to recover completely and improve its security.”

The Service Employees International Union estimates that those covered by TPS, including Haitians and many Central Americans, have 270,000 U.S.-born children and thousands of American grandchildren. According to the Washington Post, a senior official said the 18-month “wind-down” period was provided “to allow families with U.S.-born children to make decisions about what to do, and make arrangements.”

The decision does not bode well for the largest group of TPS beneficiaries, the 200,000 Salvadorans granted protected status after earthquakes hit the country in 2001. A decision on whether they must return to their country, which is plagued by gang violence and high unemployment, is expected in January.