Democrats and Republicans can’t agree on much, these days. But the profound threat that Vladimir Putin poses to our republic is one. John McCain has suggested that Russian interference in the 2016 campaign was an attack on “the foundation of democracy.” Hillary Clinton has called it a “a cyber 9/11” and “a direct attack on our institutions.” Senators, congressmen, and commentators — from both sides of the aisle — have voiced similar sentiments.

This rhetoric might be a tad hyperbolic, but it isn’t wildly so. A large (and growing) body of evidence suggests that Russian agents aided the campaign of an American presidential candidate, in hopes of furthering their own special interests — and, perhaps, gaining a sympathetic ear at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. In pursuit of this end, the Kremlin disseminated mendacious propaganda over American social media and cable news, while using stolen emails to discredit their preferred candidate’s opponent. It’s possible that Putin might have even explored leveling an attack on our electoral infrastructure itself — thereby directly barring some Americans from having their voices heard at the ballot box.

In a liberal democracy, the legitimacy of a state is founded on the integrity of its elections. Spread doubt about the latter, and the former starts to fall away. If Americans believe that their leaders do not derive their power from the popular will, but merely from the favor of shadowy puppet-masters, then civic engagement and social trust will decay. Voter participation will decline, along with confidence in public institutions. And these developments will, in turn, make it easier for bad actors to manipulate the democratic process. Eventually, cynicism about democracy could make some voters welcome the prospect of authoritarian rule. This is why it’s so vital that Russian interference in our elections is investigated and deterred.

That’s also why Congress must not pass President’s Trump’s regressive tax cuts.

That may sound like a non sequitur. The debate over tax policy in the United States is generally framed as a conflict between rival economic theories. Democrats may claim that cutting taxes on the rich will slow the economy, or drive up the debt, or force cuts to popular domestic programs. But few would put supply-side cuts on a list of threats to liberal democracy in the United States.

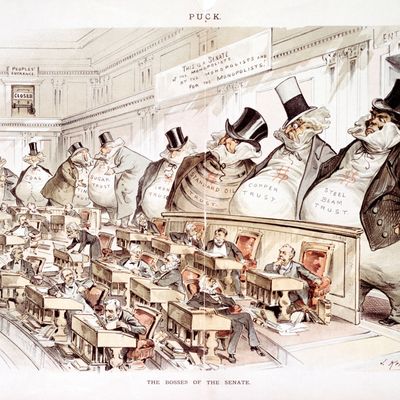

And yet, the idea that increasing economic inequality and sustaining popular sovereignty are incompatible endeavors wasn’t always alien to our politics. In fact, as the Roosevelt Institute’s Marshall Steinbaum recently noted, the New Deal reformers who brought robustly progressive taxation to the United States understood the policy as a means of altering the distribution of power in society. That the rich can easily convert their wealth into political dominance was a common-sense proposition for Americans born into a Gilded Age. Thus, the point of confiscatory top marginal rates wasn’t to maximize efficiency or growth — but to limit the monied elite’s capacity to shape the American political economy to their whims.

This argument for soaking the rich is just as salient now as it was in the robber barons’ heyday: In 2016, American billionaires aided the campaigns of their preferred presidential candidates, in hopes of furthering their special interests — and perhaps, gaining a sympathetic ear at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. In pursuit of this end, well-heeled donors funded propaganda campaigns through social media and television advertisements, while a few sought to use stolen emails to discredit their preferred candidate’s opponent. Some right-wing plutocrats even financed efforts to impose voting restrictions and felon disenfranchisement laws — thereby directly barring some Americans from having their voices heard at the ballot box.

Some may take exception to this (implicit) analogy: American elites attempting to influence our elections through political speech — and Russian operatives trying to do so through cyberattacks — are categorically different phenomena. This is certainly true; but it also does nothing to negate the premise that the political influence of American multi-millionaires, billionaires, and corporations undermines the integrity of our democracy, in many of the same ways that Russian interference does.

Does anyone really believe that RT has done more to distort Americans’ understanding of — and faith in — their political system than Rupert Murdoch’s Fox News? Or that Sputnik has had a more corrosive influence on American discourse than Robert Mercer’s Breitbart? Or that Putin’s oligarchs have done more to disconnect American policy from the popular will than the funders of the Koch network? Or that the Kremlin’s interference in our politics has done more to damage public confidence in our institutions than K Street’s?

Such claims are facially absurd. The furor over Russia’s election hacking is justified. But the discrepancy between how seriously our political elites take the threat that Russian meddling poses to our democracy — and how blithe they are about the one that concentrated wealth poses to it — is not.

It’s true that discussions of big money’s corrosive influence aren’t wholly absent from the American political conversation. But they are typically confined to debates over campaign finance laws. This is unfortunate — and not merely because the Supreme Court has erected a mountainous roadblock on the path to federal reforms. So long as the wealthiest 0.1 percent of Americans own as much as the bottom 90 percent, the threat of creeping plutocracy in the U.S. will remain — even if Citizens United and Buckley v. Valeo were somehow overturned. After all, campaign donations are just one of the many ways that well-heeled elites influence the political process — and not necessarily the most effective. Charles and David Koch’s most fruitful investments weren’t made in discrete presidential campaigns, but in funding a political network that cultivates and mobilizes conservative activists throughout the United States — and think tanks and lobbies that shape elite opinion in D.C.

It is hard to see how one can impose tight restrictions on political organizing and policy research in a free and open society — let alone, one with constitutional protections of speech as robust as our own. Pushing for more public financing of elections should be part of any plan for limiting the influence of big money in politics. But steeply progressive taxation is just as essential to that goal — and liberals would do well to emphasize this point in the upcoming debate over Donald Trump’s tax plan.

The president’s initial framework for tax “reform” would deliver 80 percent of its benefits to the top one percent of American earners, according to a preliminary analysis from the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center. It’s possible that the Republicans’ final plan will be a bit less regressive than that — but not much less so. The heart of Trump’s package is a giant tax cut for corporations, which will deliver the bulk of its (figurative and literal) dividends to wealthy shareholders and corporate executives. Other core provisions of the plan include the abolition of the tax on estates worth more than $5.5 million and a giant cut in the rate paid by wealthy “small business” owners (including the owner of a little mom-and-pop shop called “the Trump Organization”).

The stakes of these regressive cuts might strike some Americans as abstract. After all, as they raid the federal treasury for their billionaire benefactors, Republicans do intend to set aside a bit of hush money for the witnesses in the middle class. And since the GOP does not (currently) plan to attach spending cuts to their tax package, most American households will come out ahead in the near-term. Progressives can (and should) argue that these tax cuts will threaten popular domestic programs down the road. But Democrats shouldn’t rely exclusively on decrying the tax cuts’ second-order effects; not when the first-order one is to exacerbate economic inequalities that are strangling our democracy.

And there is no question that reducing the tax burden of the wealthy will swell those inequalities. Conservatives maintain that such disparities in income are a worthy price for the economic growth that supply-side tax cuts will provide to all Americans. But as the economists Thomas Piketty and Emanuel Saez have documented (along with countless other members of their profession) the correlation between regressive tax cuts and economic growth exists in Republican dogma, not empirical reality:

[D]ata show that there is no correlation between cuts in top tax rates and average annual real GDP-per-capita growth since the 1970s. For example, countries that made large cuts in top tax rates, such as the United Kingdom or the United States, have not grown significantly faster than countries that did not, such as Germany or Denmark.

While the Reagan tax cuts did not give the U.S. a significant edge over its peers in economic growth, they did give America’s economic elite a far larger share of growth than their peers in other Western countries. Crucially, this is not solely due to a predictable increase in the American rich’s post-tax income: Between the 1970s and 2013, the top one percent’s share of pre-tax income more than doubled from under 10 percent to over 20. This is not because globalization and automation inevitably create a winner-take-all economy. Japan and continental Europe have been reshaped by those forces, and yet saw no similar explosion in the income share of their rich.

Conservatives might attribute the growth in the one percent’s share to the beneficent incentives of low income-tax rates: Wealthy Americans responded to tax cuts by producing more, and thus increased their pre-tax income. And yet, if growth in the one percent’s paychecks wildly outpaces growth in the broader economy, then the rich probably aren’t getting richer by creating more value — but by extracting it. As Piketty and Saez write:

[W]hile standard economic models assume that pay reflects productivity, there are strong reasons to be sceptical, especially at the top of the income distribution where the actual economic contribution of managers working in complex organisations is particularly difficult to measure. Here, top earners might be able to partly set their own pay by bargaining harder or influencing compensation committees.

Naturally, the incentives for such “rent-seeking” are much stronger when top tax rates are low. In this scenario, cuts in top tax rates can still increase top income shares, but the increases in top 1% incomes now come at the expense of the remaining 99%. In other words, top rate cuts stimulate rent-seeking at the top but not overall economic growth – the key difference with the…supply-side, scenario.

Thus, even if tax cuts for the rich aren’t financed by spending cuts, ordinary Americans have nothing to gain from them — and much to lose. Since the Reagan tax cuts, workers have seen their share of productivity gains plummet; the gap between the wealth of rich and poor households — along with that between white and black ones — has exploded; the middle class has become more reliant on debt to finance their homes, automobiles, and children’s educations; the amount of money that corporations and wealthy individuals invest in influencing American politics has skyrocketed; and policy-making has become ever-more tilted to the needs of these economic elites as a result.

Virtually everything that we fear Russian interference could do to our democracy, these inequities have done already. Over the past four decades, Americans have become increasingly convinced that their nation’s political and economic systems are rigged against them. In November 2015, a Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) survey found 64 percent of Americans agreeing with the statement, my “vote does not matter because of the influence that wealthy individuals and big corporations have on the electoral process.” One year later, 75 percent of 2016 voters told Reuters/Ipsos that they were looking for a “strong leader who can take the country back from the rich and powerful.”

Meanwhile, social trust, civic engagement, voter participation, and confidence in public institutions have all fallen precipitously. Polls show Americans are losing faith in democracy itself, and are growing more sympathetic to authoritarian appeals.

Absent this context of disillusion and distrust, it’s unlikely that Trump’s demagogic campaign (or the Kremlin’s attempts to aid it) would have stood much chance of success.

“The economic royalists complain that we seek to overthrow the institutions of America,” Franklin Roosevelt famously said at the 1936 Democratic convention. “What they really complain of is that we seek to take away their power. Our allegiance to American institutions requires the overthrow of this kind of power.”

As Republicans work to consolidate the power of those royalists in the coming months, Democrats should (once again) call for their overthrow.