The Senate GOP’s tax bill cannot pass the Senate. This statement is not a conjecture about political realities, just a report of a mathematical one.

For 11 months now, the challenge facing Republican tax writers has been clear: Find a way to radically reduce the tax burdens of corporations, owners of “pass-through” businesses, heirs to multimillion-dollar estates, and a critical mass of the middle class — without increasing the deficit ten years after such tax cuts go into effect.

That final, formidable obstacle derives from the rules of the Senate. The GOP’s tax agenda is too conspicuously regressive to attract much — if any — Democratic support. But the party only has 51 seats in the Senate, which is nine too few to pass regular legislation over a Democratic filibuster. Thus, Republicans need to pass their tax cuts through budget reconciliation — a special process that allows bills to clear the Senate without facing a filibuster, so long as said bills don’t increase the deficit one decade after passage. This requirement is named “the Byrd rule,” after the senator who established it.

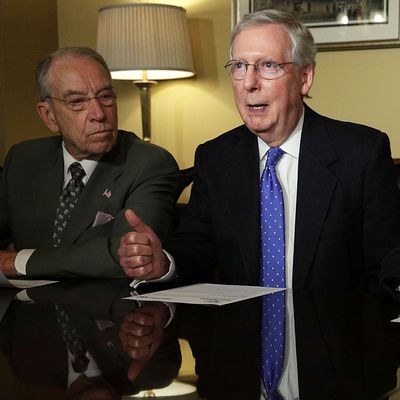

The Republican Party has produced a lot of tax plans over the first year of the Trump presidency. But none have complied with the Byrd rule. And the bill that Mitch McConnell’s caucus unveiled Thursday was no exception.

This fundamental failure was obvious from the moment the text of the legislation was released. But it wasn’t clear just how far Senate Republicans had fallen short, until Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation released their official score of the bill Thursday night.

To meet the conditions of budget reconciliation, the bill would have to produce no revenue losses, beginning in 2028. Thus, Republicans ostensibly hoped that the JCT would find their bill producing smaller and smaller deficits over time. Instead, the committee found that the GOP plan would produce its largest deficit — $216.7 billion — in 2027.

You can’t erase $200 billion in annual deficits through budget gimmicks, alone. You can’t do it through giving the existing bill a nip and tuck. Heck, you can’t even do it by ripping out the heart of the GOP plan: Republicans could leave the current corporate tax rate at 35 percent, and their bill would still be too expensive to pass.

What’s more, the Senate legislation relies on the repeal of the state and local tax deduction for more than $1 trillion of its new revenues. But House Republicans have already signaled that they don’t have the votes to repeal that benefit. So, in all probability, Mitch McConnell has far more than $200 billion a year to make up, if he wishes to pass Trump’s tax plan into law.

All of which is to say, nothing resembling the president’s tax plan will ever comply with the Senate’s existing rules. It is not mathematically possible. This shouldn’t be surprising: Republicans aren’t just trying to deliver massive tax-rate cuts without increasing the long-term deficit — they’re also committed to doing so without attaching any significant spending cuts, or eliminating the most popular (and expensive) tax deductions.

The GOP still might be able to pass a modest, temporary tax cut. But Paul Ryan’s dream of passing a giant, permanent reduction in America’s corporate tax rate is dead — unless the filibuster dies first.

Right now, the Senate bill’s primary problem is mathematical. But the roots of that math problem are political. While Senate Republicans need 60 votes to pass their plan under the upper chamber’s existing rules, they can change those rules with 51.

McConnell has repeatedly ruled out a formal abolition of the filibuster. But that rule can be informally eliminated through a variety of means. The Joint Committee on Taxation may say that the GOP bill adds to the deficit in 2028. But Senate Republicans don’t need to let Congress’s official umpire call balls and strikes. They can technically solicit a score from a maniacal supply-sider — one who will tell them that their bill actually pays for itself by producing 10 percent growth — and then declare the Trump plan Byrd-compliant. Or they could use the existing score, and then just overrule the parliamentarian when she declares the bill noncompliant. Or they could rewrite the Byrd rule, so that it only prohibits bills from adding to the deficit 40 years after they’re passed — and then, phase out all of their tax cuts in 2050 (which would make them about as “permanent” as any legislation in a democracy ever can be).

Any of these measures would, for all practical purposes, end the legislative filibuster. If the majority party can pass whatever it wants through budget reconciliation by adjusting the rules to suit their ambitions, then it’s game over. In the long run, this would probably be a positive development for our democracy. But the conservative movement has a long-term interest in preserving the status quo: A system where Democrats need 60 votes to enact new regulations or expand the welfare state, but Republicans need only 51 to cut spending, is a system that benefits the right. Considering how easy it is to imagine Democrats reclaiming power in the next few years — and how hard it is to see the party assembling 60 Senate votes — it would seem rather myopic for Republicans to go nuclear at this point in time.

Even if scrapping the filibuster made long-term strategic sense for the right, it’s far from clear McConnell would have the votes to kill it. John McCain is a die-hard institutionalist. Jeff Flake and Bob Corker have both suggested they’ll oppose any tax plan that radically increases the deficit. And it’s pretty hard to see Susan Collins signing on to a plan to make the Senate more partisan and less deliberative. None of these senators have anything to lose by sticking to their guns. Collins is one of the most popular senators in the country; Flake and Corker will soon be leaving the Senate; McCain is (in all likelihood) not long for this Earth.

Nevertheless, it is technically within Senate Republicans’ power to gut the filibuster. And it is manifestly not within their power to pass the Trump tax cuts under existing Senate rules. So, the only relevant question about the Senate bill’s prospects, at this point, is whether McConnell has the votes for a procedural revolution in the upper chamber.

If he doesn’t, Republicans might still enact some kind of tax cut. But it won’t be anything like the one that they’ve spent the last 11 months promising to pass.