It is a testament to the power of self-delusion that Republicans have convinced themselves that their political self-interest demands that they pass a deeply unpopular tax-cut plan. The House has designed a proposal that not only violates Senate budget rules but seems virtually designed to seed an endless supply of attack ads against congressional Republicans.

A Washington Post poll provides a good starting point for measuring public opinion at the outset of the tax debate. Only one-third of Americans support the plan, against half opposing it. Sixty percent of the public believe it favors the rich. To the extent that people learn more, support is likely to fall even lower.

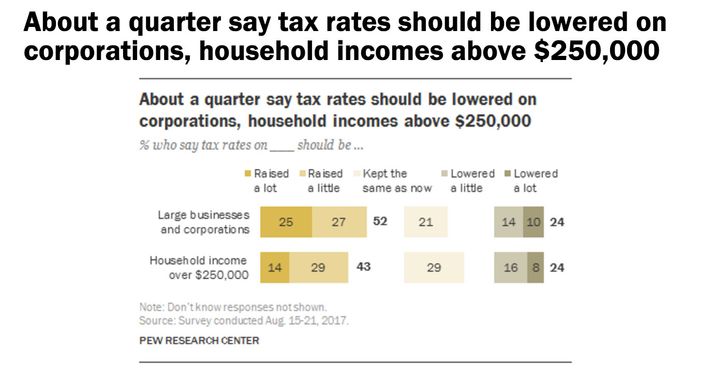

The bill contains three categories of political poison. First, it cuts taxes on rich people and corporations, a wildly unpopular goal. Americans want to raise taxes on corporations and people with high incomes. Republicans would do the opposite:

The bill accomplishes this unpopular change by reducing the corporate income tax rate, raising the threshold at which the top income tax rate applies, from $400,000 to a million dollars, phasing out the estate tax, and creating a 25 percent income tax bracket for “pass-through firms.” The latter provision is rife for both abuse and lawyerly gaming. Any time the tax code makes a lot of money hinge on a technical difference, the opportunities for fraud will multiply. In this case, high-income earners who want to reduce their income tax rate from 39.6 percent or so to 25 percent can create a phony firm in which they are an investor.

“Here’s a tax-planning trick that occurs to me right off,” suggests NYU tax law professor Daniel Shaviro.“I’m a plutocrat and so are you. If we just got the $$ from our own businesses, in which we’re working actively, we’d only get the low rate for 30 percent of our net business income. But if we invest in each other’s business, 100 percent, since we’re passive as to the other person’s business.”

Even the Wall Street Journal editorial page, which defends the plan, recognizes the problem. “Republicans should not want to defend Wall Street lawyers paying a lower rate than wage earners in Omaha,” it warns. But they will be.

The second problem is that the bill raises taxes for a large number of middle-class families. It does so by scaling back personal exemptions and reducing the inflation adjustment. Around a quarter of middle-class families will pay more taxes under this plan. That’s millions of people. (Or, to translate it into attack ad–ese, “MILLIONS of Middle-Class American families will get a TAX HIKE so CORPORATIONS CAN PAY LESS!”)

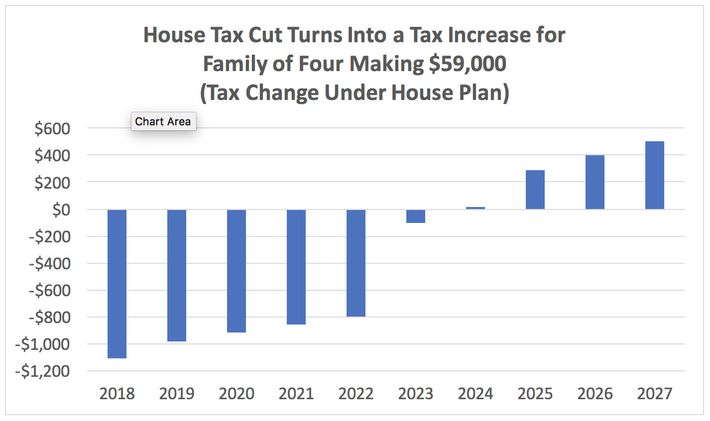

House Republicans tout a married couple with two children earning $59,000 as the prototypical beneficiaries of their plan. It is true, such a couple would pay lower tax in the first few years. But as time goes on, their tax cut will turn into a tax increase:

Many of those couples, or perhaps actors portraying them, will be seen on television between now and November 2018 making sad faces around their kitchen tables.

Finally, the House Republican plan eliminates specific tax breaks that are both worthy and popular. There are two fiscal requirements for a tax plan to pass the Senate. It can increase the deficit by no more than $1.5 trillion over the first decade, and it cannot increase the deficit at all after ten years. The House plan utterly fails the second test, which makes it unpassable in anything like its current form, and raises the question of why they’re bothering to take all the political risk.

But it does meet the first requirement. And in order to keep its net cost down to $1.5 trillion, when the tax cuts it gives out cost much more, Republicans went scrounging through the cushions of the tax code for loose change. And the nickels and dimes they’re saving to pay for the corporate and estate tax cuts include things like eliminating the tax credit that offsets the (frequently exorbitant) cost of adoption. Or the tax credit for small business to create access for disabled employees. Or the tax credit for clinical tests for treatment for rare diseases — which, the New York Times explains, is “central to the business model for such firms and eliminating it could mean that big pharmaceutical companies will have little reason to invest in drugs that help small patient populations.” Or repealing the Work Opportunity Tax Credit, which creates an incentive for hiring veterans.

The plan reads as if it was reverse-engineered from 30-second political attack ads. And while it seems very unlikely that Republicans actually designed their proposal by asking Democratic ad-makers for a list of the most sympathetic people in America — veterans, orphans, the disabled, people suffering rare diseases — the effect will be the same.

Republicans could have written a tax-cut plan that hurt nobody. Or they could have written a sweeping tax reform that could stand for years. Incredibly, they have done neither. They have taken on all the political downside of tax reform — but because their plan can’t pass the Senate, they will get none of the upside.