Reality, Tina Satter’s play-turned-film starring Sydney Sweeney as Reality Winner, is now on HBO.

Reality Winner grew up in a carefully kept manufactured home on the edge of a cattle farm 100 miles north of the Mexican border in a majority-Latino town where her mother, Billie, still lives. From the back porch, a carpet of green meets the horizon, and when a neighbor shoots a gun for target practice, a half-dozen local dogs run under the trailer to hide. Billie worked for Child Protective Services, and in Ricardo, Texas, the steady income made her daughters feel well-off; the fact that they had a dishwasher seemed evidence of elevated social standing. Billie, a chatty redhead with the high-pitched voice of a doll, supported the family while her husband, Ronald, she says, “collected degrees.” It was Ronald who named Reality. The deal had been that Billie got to name their first — Brittany — but their second was his to choose. He noticed, on a T-shirt at their Lamaze class, the words I COACHED A REAL WINNER. He wanted a success story and felt that an aspirational name would increase his chances of producing one. Billie did not object; a deal is a deal.

Ronald was intellectually engaged, though never, during his marriage, employed, and Reality’s parents separated in 1999, when she was 8. Two years later, when the Towers fell, Ronald held long, intense conversations about geopolitics with his daughters. He was careful to distinguish for them the religion of Islam from the ideologies that fueled terrorism. “I learned,” says Reality, “that the fastest route to conflict resolution is understanding.” She credits her father with her interest in Arabic, which she began studying seriously, outside school and of her own accord, at 17. It was this interest in languages that eventually drew her into a security state, unimaginable before 9/11, that she chose to betray. Fifteen years after those first conversations with her father, Reality’s interest in Arabic would be turned against her in a Georgia courtroom, taken as evidence that she sympathized with the nation’s most feared enemies.

Reality was an almost comically mature adolescent, intellectually adept, impatient with her peers, with a compulsive drive to improve herself she would eventually channel into an obsession with nutrition and exercise. Her body was strong and substantial and unadorned: thin blonde hair tied up, no makeup, clothes that suggested a lack of interest in the act of dressing. She was shy and shyly mischievous. In the eighth grade, she organized a food fight so intense that she was banned from walking during graduation, though her mother points out that she was careful not to schedule it during spaghetti day, when it would have been especially messy.

Reality agreed to date her high-school boyfriend, Carlos, on certain conditions intended to improve and to edify. Carlos, who was failing out of school and broke, had to read a particular number of books a week. He had to maintain at least a C average. He had to get a job. He did not have clothes suitable for employment, but Reality would work on that; she had her mother take Carlos shopping for khakis and a polo. “Reality takes in a lot of strays,” says her mother with a sigh, “and I don’t mean just animals.”

She was a talented, stylish painter, and her most frequent subjects were herself, Nelson Mandela, and Jesus. She was an inveterate smasher of phones. She threw one across the room while talking to her father, who struggled with an addiction to painkillers and who she sensed was stoned, and cracked another one falling from a tree she’d climbed in a fit of whimsy. A third phone met its fate when it simply wasn’t working. “How hard is it to be a phone?” she yelled, threw it, smashed it.

Reality was raised six miles from a naval base, in a household where humanitarian and military motives were not taken to be in tension, at a moment, just after 9/11, when the country had mostly unambivalent feelings about the moral might of its armed forces. “What could be more humanitarian,” Billie asks, “than protecting your country and innocent victims of war and terrorism?” As an adolescent, Billie had dreamed of joining the Air Force herself but ended up advocating for abused and neglected children as a social worker. During Reality’s senior year, an Army recruiter came to her high school and zeroed in on her as a smart, athletic potential recruit. He took her out to lunch at a Kingsville Whataburger multiple times a week, for several weeks, until she agreed to take an assessment test.

No one was surprised when Reality’s sister, Brittany, went on to college, absurd amounts of college, such that she walked out of Michigan State with a Ph.D. in pharmacology and toxicology last year. But Reality had then, and has now, a skepticism of academic degrees, which she recently described to me as “hundred-thousand-dollar pieces of paper that say you’ve never had a job.” (“It’s interesting,” her mother notes, “because of her father?”) She wanted her life to start. She wanted to make the biggest difference she could, as soon as she could. It wasn’t until she was getting on the bus for basic training that she told her mother she’d applied to engineering school at Texas A&M–Kingsville, received a full scholarship, and turned it down.

Based on her test scores, Reality was selected to be a cryptolinguist, which is to say she was tapped to help the military eavesdrop on people speaking languages other than English. She wanted Arabic, but the ones assigned to her were Dari and Farsi — languages of use to a military vacuuming up conversations from Afghanistan and Iran. She would spend two years becoming fluent and another year in intelligence training before she was sent to Maryland’s Fort Meade. Along the way, she’d be one of a few students admitted to a selective program in Pashto, yet another language in which she would become fluent.

In Maryland, her life, according to those closest to her, involved an exceptionally punishing exercise regimen, volunteer work, and 12-hour shifts listening to the private conversations of men and women thousands of miles away. There was also anxiety. Reality worried about global warming. She worried about Syrian children. She worried about famine and poverty all over the globe. Highly critical of her carbon-spewing, famine-ignoring fellow citizens, she nevertheless thought her humanitarian impulses were compatible with the military’s mission, and wished her fellow Airmen were not just more competent in their jobs but more motivated to do them well, to save the vulnerable from acts of terror.

To those around her, Reality was a never-ending, frequently exhausting source of information on the world, its problems, and our collective obligation to pay attention. She gave her sister a marked-up copy of the Koran, rife with Post-it notes, and told her to read it. With an organization called Athletes Serving Athletes, she pushed wheelchair-bound kids through half-marathons. (“Athletes Serving Athletes,” said her ex-boyfriend Matt Boyle. “She’d never shut up about that.”) She donated money to the White Helmets, a group of volunteers performing search-and-rescue missions deep in rebel-held Syria. She told those around her to watch 13th, a documentary about racial injustice in the prison system.

On Facebook, where she called herself Reezle Winner because the site had rejected her legal name, she friended her yoga instructor, Keith Golden. “I was like, Who the fuck is Reezle?” said Golden. Thereafter he called her “Diesel Reezle.” He had, as everyone around Reality did, the sense that she was an extremely competent linguist. “I’d say, ‘I bet you dominate that military shit, they fucking love you, don’t they?’ And she’d say, ‘Well, yeah, I’m good at my job.’ ”

What remained abstract and distant to the news-consuming public was neither abstract nor distant to Reality. “She was really, really passionate about Afghanistan and stopping ISIS,” says Golden. “We would go to lunch, and that’s pretty much all she would talk about. She was despondent that ISIS was the way that it was, that we can’t do anything to help the whole situation, that it’s so fucked up.”

The people closest to her did not know precisely what Airman Reality L. Winner did during her 12-hour shifts at Fort Meade. They only knew that there were certain days when she knew something big was coming and went to bed early. Reality told her mother that she might have PTSD. If she were to explain the nature of her work stress to a therapist, she would risk being charged with espionage. She exercised, and she journaled. She kept thick diaries full of small text, Post-it notes scrawled to the margins. She wrote down instructions, inspirational quotes, arguments she was having with herself. A couple of times a week, for hours at a time, she would talk to her father, whose health was failing but who was constantly watching the news. They discussed current events of concern to her, like the war in Syria.

Reality would later tell the FBI that she worked in the drone program; as a cryptolinguist, her job would likely have been to translate communications so that drone operators would know whom to target. “It was definitely traumatizing,” says Boyle. “You’re watching people die. You have U.S. troops on the ground getting shot at, you miss something, a bomb goes off, and you get three people killed.”

As a matter of record, she helped kill hundreds of people. A commendation she received in October 2016 praises her for “assisting in geolocating 120 enemy combatants during 734 airborne sorties.” She is commended for “removing more than 100 enemies from the battlefield.” She aided in 650 “enemy captures” and 600 “enemies killed in action.”

In January 2015, ISIS militants locked a 26-year-old Jordanian pilot in a cage, soaked him in gasoline, touched torch to fuel, and filmed him as he slowly burned alive. Reality was deeply upset and full of fury, as she often was, for the Islamic State. “Getting out of work,” she wrote in an email to Golden, “I felt such a rush of emotion that I had been suppressing throughout the shift. I could not escape, or allow myself to put aside thoughts about the Jordanian pilot … I spent hours playing mental chess with the world, who should strike first, hardest, what message should be sent, revenge, etc. … So on all fronts I just felt really helpless and overwhelmed. Naturally my thoughts had turned to yoga, because it is the means by which I can really understand and acknowledge powerful emotions and put them aside to gain more clarity and peace. But I didn’t want to just hide in asana and meditation because it made me feel good. In the pain I felt, I did not want the ‘moral’ to be compassion and forgiveness.”

Golden hadn’t even heard about the pilot. “I had to Google it,” he told me, “because I don’t really follow the news.”

Reality’s favorite part of the job was “saving lives,” but this was not, in the end, the way she wanted to save them. She wanted to do something humanitarian and directly so; she had thought the Air Force could make that possible by sending her abroad to places in need of her language skills and drive to help. In her daydreams, Reality passed shoe boxes full of toys to children in refugee camps in a war-torn country on Christmas morning. She knew that this was not realistic, that this was not what was needed, and she treated this dream with a wry, self-deprecating lightness. She gave what was actually needed: money to the Red Cross, donations to the White Helmets. Then she went back to work transcribing the tapped communications of suspected militants 7,000 miles away.

Disappointed that the Air Force was not sending linguists like her into the field, Reality began to look elsewhere for fulfilling work. She was honorably discharged in November 2016, at which point she applied for jobs with NGOs in Afghanistan, hoping to use her Pashto to actually talk to people — maybe refugees, maybe kids on Christmas morning. That same month, she began to test the boundaries of her oath to keep information secret. Reality says she wanted to know how her colleagues had uploaded personal photos onto their secure computers. She searched using the phrase “Do top secret computers detect when flash drives are inserted” and inserted a thumb drive. According to Reality, an admin box popped up. She didn’t have the password. She ejected the drive.

Reality’s search for work abroad was frustrating. Her nonmilitary education stopped at high school, which is perhaps why her applications went nowhere. “They want a degree to hand out blankets,” she told her mother. She was one of an infinitesimal number of Americans fluent in multiple Afghan languages, and yet she could not find a way to get out of an American office park.

During her years in the Air Force, Reality had, for a time, deployed to Fort Gordon, a base near Augusta, Georgia. After she was discharged, she got in her boxy, bumper-sticker-covered Nissan Cube (ADOPT! / MAKE AMERICA GREEN AGAIN! / YOU JUST GOT PASSED BY A TOASTER), packed her belongings — which included an AR-15, a Glock, and a 12-gauge shotgun — and moved back. She taught at a CrossFit place, a high-end boutique gym, and a yoga studio while she tried to find a way to go abroad. Months passed. Around this time, she downloaded a Tor, a browser that allows for anonymous communication. Reality says she was curious about WikiLeaks, about how it all worked. She opened it up at a Starbucks, checked out the site, and was underwhelmed. She closed it again.

Reality did not have a college degree, but she was one of 1.4 million Americans with Top Secret clearance, which is to say that she had something to sell. Contractors are sometimes called body shops, and the bodies they want are security-cleared, readily found on sites like clearedconnections.com, which Reality frequented. Augusta was full of contractors paying good money for cleared linguists, and Reality accepted a job with Pluribus International, a small operation owned by the son of a former CIA operative.

By December 2016, when Reality returned to Georgia, it was common for a certain class of educated and politically sophisticated people to refer to the “deep state,” a term that conjures dark-suited men self-satisfied in their grim capacity for discretion. This image fails to account for the fact that those 1.4 million hold top security clearance; that most of the intelligence budget now redounds to private contractors employing tens of thousands of middle-class Americans; that armies of security-cleared analysts are required to sift through all the data the state collects. If your definition of “deep state” cannot accommodate an idealistic 25-year-old CrossFit fanatic with unmatched socks, you’ve underestimated both the reach and scope of American surveillance.

To get to the second floor of the Whitelaw Building, where Reality Winner appears to have worked from February until June, she first had to drive into Fort Gordon, “Home of the U.S. Cyber Center of Excellence,” past low-slung brick buildings and uniformed military in formation, past massive satellite dishes behind barbed wire, toward the $286 million, 604,000-square-foot sleek white listening post that is NSA Georgia, gleaming and gently curved, surrounded by a parking lot full of the middle-class cars of working intelligence-industry professionals.

I took this drive in October, after I’d been given a visitor pass at the entrance to the Army base. I drove until I arrived at a building that looked like renderings I’d seen before and walked around feeling perfectly invisible. After five minutes or so, a black SUV pulled up with a police officer inside; she demanded my license. “Woman in a burgundy top” was the efficient way I had been identified in her notepad. Another SUV pulled up. The police officer called the men inside “special agents,” though when I asked a guy for his title, he declined to say. There were two officials, then three, then six, and they were “just trying to figure out what’s going on.” I asked a few times if I could leave and was told I could not in fact leave; I asked if I was under arrest and told no, this was “investigatory detention.” I was then turned over to a third jurisdictional authority, military police, who drove me off the base.

The Whitelaw Building is one of many facilities built all over the country with the government largesse produced by 9/11, in a decade when spending on intelligence more than doubled and the intelligence community, once concentrated in and around greater Washington, D.C., spilled over into places like St. Louis and Salt Lake and San Antonio. It is a pair of coordinates in the “alternative geography” described at length by Dana Priest and Bill Arkin in their 2010 “Top Secret America” series for the Washington Post, one small part of a huge, hidden world of mile-long business parks, unmarked city buildings, and ghost floors in bland suburban high-rises.

Surveillance requires surveillors; mass surveillance requires more of them. In 2011, according to a document leaked by Edward Snowden, the number of people who worked for the 16 agencies that the government considers to be part of the intelligence community was 104,905. But that number doesn’t include contractors, to which most intelligence funding — 70 percent, according to a PowerPoint leaked to investigative journalist Tim Shorrock — now accrues. Precisely how many Americans are involved in the country’s $70 billion intelligence project remains unknown, probably, even to members of the inner circle; senior officials marvel at its size and redundancy. The intelligence contractors Booz Allen Hamilton, CRSA, and SAIC each employ well over 15,000 people, and there are hundreds of smaller companies like the one for which Reality worked. A single Army research-laboratory contract inked in 2010 involved 11 “prime” contractors and 180 subcontractors. This contract, and these numbers, also come to us via leak.

With so many having access to so much, the fabric of secrecy is stretched thin, vulnerable to puncture. And so the Obama administration launched an unprecedented crackdown against whistle-blowers, charging more of them under the Espionage Act of 1917 than all previous administrations combined. To “detect and prevent” potential leakers, the Obama administration introduced something called “insider threat” training.

“What do insider threats look like?” asks a student guide prepared by the Center for Development of Security Excellence. “They look like you and me.”

Materials used for this training encourage employees to look out for co-workers who “display a general lack of respect for the United States.” The phrase “way of life” comes up frequently, as in “Through unauthorized disclosures … we all risk losing our way of life,” and “When you protect classified information you are protecting our nation’s security, along with the warfighters who defend our American way of life.”

Reality characterized her own insider-threat training as “five hours of bitching about Snowden.”

“I have to take a polygraph where they’re going to ask if I plotted against the government,” she messaged her sister in February. “#gonnafail.”

“Lol! Just convince yourself you are writing a novel.”

“Look, I only say I hate America three times a day. I’m no radical.”

Reality Winner would have been making the best money of her life at Pluribus, but she had never been particularly interested in what money can buy. She rented, sight unseen, an 800-square-foot house in a part of Augusta the Atlanta Journal-Constitution calls “hardscrabble” and her ex-boyfriend calls “blighted”; her neighbors parked their cars on brown, patchy lawns. (“I did not look at a map when I signed the lease,” she’d later tell the FBI, “but I’m well armed.”) The rooms were filled with workout equipment, sneakers, and sticky notes on which were scrawled workout regimes (“Bench 5x5, Back Squat 5x5”) but also stray thoughts about issues with which she was preoccupied (“Peace-making is less of a rational-economic model of dividing resources and territory fairly”; “Further research: Deserts versus rainforest”). Months later, when her mother walked me through the house, she’d point to Reality’s room and say, “The world’s biggest terrorist has a Pikachu bedspread.”

Reality was searched for thumb drives and cell phones every morning as she walked into the Whitelaw Building; her lunch, security guards noted as they pawed through it, was very healthy. She translated Farsi in documents relating to Iran’s aerospace program, work for which she had no particular affinity and which seems to have bored her. For those mornings when she did not feel like reading more documents about Iran’s aerospace program, she evidently had access to documents well outside her area of expertise. She had access, for example, to a five-page classified report detailing a Russian attempt to access American election infrastructure through a private software company. This would be, ultimately, the document she leaked. According to the analysis in the report, Russian intelligence sent phishing emails to the employees of a company that provides election support to eight states. After obtaining log-in credentials, the Russians sent emails infected with malware to over 100 election officials, days before the election, from what looked like the software company’s address.

In November, the man Reality referred to as “orange fascist” became president of the United States. That fall, Reality and her then-boyfriend Matt Boyle stopped seeing one another, and four days before Christmas, her father died. Though she kept it to herself at the time, she would later tell her sister that she would cry for 30 minutes a day, every day, during the weeks after his death. (“That sounds like Reality,” says Boyle. “She would give herself exactly 30 minutes.”) “I lost my confidant,” she later wrote in a letter, “someone who believed in me, my anger, my heartbreak, my life-force. It was always us against the world … It was Christmastime and I had to go running to cry to hide it from the family. 2016 was the year I got really good at crying and running.”

Her father had always talked about going to Belize to see the ruins, and so she decided to go on a three-day trip in memory of him. She returned to a workplace at which she was increasingly unhappy. It bothered her that the screens at NSA Georgia were always tuned to Fox News, and it bothered her enough that she filed a formal complaint. In her free time, she sought out the staff of David Perdue, the U.S. senator from Georgia, and arranged a 30-minute meeting to discuss climate change and the Dakota Access Pipeline; on Facebook, she explained that she had drawn for Perdue’s staff “a parallel between the 2011 interview of President Bashar al Assad claiming utter ignorance of the human rights violations his citizens were protesting” and Trump’s claim that the White House had received no calls about the Dakota Access Pipeline.

In those first months on the job, the country was still adjusting to Trump, and it seemed possible to some people that he would be quickly impeached. Reality listened to a podcast called Intercepted, hosted by the left-wing anti-security-state website the Intercept’s Jeremy Scahill and featuring its public face, Glenn Greenwald, and listened intensely enough to email the Intercept and ask for a transcript of an episode. Scahill and Greenwald had been, and continue to be, cautious about accusations of Russian election meddling, which they foresee being used as a pretext for justifying U.S. militarism. “There is a tremendous amount of hysterics, a lot of theories, a lot of premature conclusions being drawn around all of this Russia stuff,” Scahill said on the podcast in March. “And there’s not a lot of hard evidence to back it up. There may be evidence, but it’s not here yet.”

There was evidence available to Reality.

The document was marked top secret, which is supposed to mean that its disclosure could “reasonably be expected” to cause “exceptionally grave damage” to the U.S. Sometimes, this is true. Reality would have known that, in releasing the document, she ran the risk of alerting the Russians to what the intelligence community knew, but it seemed to her that this specific account ought to be a matter of public discourse. Why isn’t this getting out there? she thought. Why can’t this be public? It was surprising to her that someone hadn’t already done it.

Those who criticize whistle-blowers often suggest that the offender ought to have followed a more “responsible” course — what Obama once called in his criticism of Snowden the “procedures and practices of the intelligence community.” There are reasons notorious leakers have stopped doing so, and those reasons involve a man named Thomas Drake. In 2002, Drake had concerns about a wasteful and unconstitutional $1 billion warrantless-wiretapping program later revealed to be among the worst and most expensive failures in the history of U.S. intelligence. He alerted the NSA’s general counsel, informed Diane Roark, a Republican staffer on the House Intelligence Committee in charge of NSA oversight, and, anonymously, informed congressional committees investigating the mistakes that led to 9/11. He alerted the inspector general of the Department of Defense, which launched an investigation. Colleagues warned him that he ought to stop. Eventually, the FBI raided Drake’s home and the Justice Department charged him with “willful retention of national defense information.” An assistant inspector general later claimed that the Pentagon was punishing Drake for whistle-blowing and had improperly destroyed material related to his defense. Drake lost his job, his pension, and his savings. His marriage fell apart. He now works at the Apple store in Bethesda, Maryland.

William Binney, a longtime NSA technical director, went to both the inspector general of the Department of Defense and Roark, with complaints about massive amounts of wasteful spending; the FBI raided his home, pointed a gun at him while he was in the shower, and revoked his security clearance. He was 63. (For good measure, they raided Roark’s house, too.)

Drake and Binney, among others, had attempted to work through the system, only to be retaliated against. But something shifted in 2010, when a 22-year-old private named Bradley Manning sent a trove of secrets straight to WikiLeaks. Snowden, 29, went to particular journalists he trusted (one of whom was Greenwald). These whistle-blowers spent far less time at their respective agencies or contractors and had considerably less faith that their superiors might be sensitive to their concerns. They were in their 20s, a time of great ideological foment for many intelligent people, and an age at which many are at their most ideologically rigid. Snowden and Manning were not career service people who had grown concerned with the way some work being done by colleagues violated the values of the institution in which they still believed, but newcomers — an IT contractor and a soldier — suddenly face-to-face with the whole system of American surveillance. And Snowden, in particular, knew exactly what happened to people who followed proper channels.

“The disclosure system, the whistle-blower system, the ability to bring wrongdoing and questions about policy, is fraught with corruption,” says Drake, who speaks mostly in a kind of outraged abstraction. “It does not protect the whistle-blower, the truth-teller. It’s designed to ferret them out and hammer them from within.”

For those inside the web of secrecy, that makes a bad mood on a bad day, a snap decision in the midst of a quarter-life crisis, potentially catastrophic.

The classified report on the Russian cyberattack was not a document for which Reality had a “need to know,” which is to say she wasn’t supposed to be reading it in her spare time, let alone printing it, and were she to print it for some reason, she was required to place it in a white slatted box called a “burn bag.”

Why do I have this job, Reality thought, if I’m just going to sit back and be helpless?

Reality folded up the document, stuffed it in her pantyhose, and walked out of the building, its sharp corners pressing into her skin. Later that day, President Trump fired James Comey, who had been leading an investigation into Russian election-meddling. Reality placed the document in an envelope without a return address and dropped it in a standing mailbox in a strip-mall parking lot. Court documents suggest she also sent a copy to another outlet, though which one we don’t know.

When the envelope first arrived at the Intercept, there was considerable doubt that the document within it was real. The reporters decided, per standard journalistic practice, to contact someone who could verify its authenticity. What is less standard — what Thomas Drake calls “abhorrent” and Tim Shorrock calls “just shameful” and investigative journalist Barton Gellman called “egregious” — is for a reporter to provide a copy of the document itself, which could help reveal precisely who had provided it. On May 30, according to court filings, an unnamed reporter sent pictures of the document to a contractor for the U.S. government and told the contractor that they’d been postmarked in Augusta. The contractor initially said that the documents were fake but, after checking with someone at the NSA, reported that they were real. (The Intercept declines to comment for this story, though its parent company is contributing to Reality’s defense.)

On June 5, under the headline “Top Secret NSA Report Details Russian Hacking Effort Days Before 2016 Election” and bylined by four reporters, the Intercept published a scan of the leaked document with some redactions. The document it had incidentally given to the NSA — which had then sent it to the FBI — and which was now freely available on the internet, shows creases that suggest it was printed, folded, and carried, rather than submitted online. It contains watermarks indicating that it was printed on May 9, 2017, at 6:20 a.m., from a printer with the serial number 535218 or 29535218. The NSA knew, from its internal surveillance, that only six people had printed the document. Of those six, only one had emailed the Intercept asking for a transcript of a podcast.

Reality quickly confessed to the FBI agents who came to her home to get her, a confession she would later contest because she was not read her Miranda rights. As she awaited her bail hearing, she was held in the Lincoln County Detention Center, an afterthought of a holding cell in small-town Georgia. Seven other women, all of whom were there on drug offenses, passed their days alongside Reality in a single room stacked with bunk beds, loud with the blare of television. This would be the place Reality would have to await trial — a process that would take many months — if she were not granted bail at a preliminary detention hearing.

She called her sister and sounded terrified. “Oh, boy, Britty, I screwed up,” she said. “I don’t know if I’m getting out of this one … I just, I can’t even get over the little things, like I was supposed to teach yoga today, I was supposed to be on a date last night. I know it’s stupid, but that’s my whole life, that’s all I had—”

“It’s not stupid,” said Brittany, and pointed out that her husband’s first concern was that Reality would refuse to eat any of the jail food.

“I was like, ‘The only thing she eats is kale, so …’ ”

“I know, I feel absolutely terrible, there’s so much white bread here, I … I—”

“I’m sorry I’m laughing at you,” said Brittany, laughing.

They joked about Orange Is the New Black, and Reality, embarrassed but unable to shake the worry of obligation, asked her sister to arrange for a substitute for a cycling class she taught, then returned to feelings of hopelessness.

“I feel like I’m being a diva,” she said, “like there are freakin’ Syrian refugees that have nothing but still go from one day to the next.”

“I think it’s still going to be okay,” said Brittany.

“I didn’t think. I did not think of the consequences for even a second.”

“You’re going to get through this.”

“I keep telling myself to act more like I did something wrong,” said Reality, and laughed.

“Well, maybe you’re right,” said Brittany, “I don’t mean to discount the effect of being pretty and white and blonde. I’m kidding.”

“I’m definitely playing that card. I’m going to look cute like …”

Brittany was laughing.

“I’m going to—”

“Cry a lot.”

As an advocate for children at Child Protective Services, Billie Winner was familiar with courtrooms and proceedings. Reality, she reasoned, was not a flight risk. She could safely come home and await trial. It would all work out.

Reality, blonde hair in a bun, in an orange jumpsuit with the words inmate stitched in yellow on the chest, was led into the courtroom in handcuffs by two armed U.S. Marshals. Inside the room, her cuffs and a chain around her waist were removed, but the Marshals stood before her the entire time. Her mother and stepfather waited outside the room to be called in.

Reality had written everything down. Assistant prosecutor Jennifer Solari described journals the FBI had seized from Reality’s home: notes she had made in a foreign language the prosecutors could neither read nor identify, jobs abroad she wanted to apply for, “two notebooks containing … numerous doodles of the defendant’s own name.” Among the minutiae of her life, the workouts and the worries, scribblings about dental insurance at her new job, prosecutors also found this: “I want to burn the white house down, find someplace to live in Jordan or Nepal. Ha ha. Maybe.” She had written, elsewhere, “Perhaps bin Laden was the Judas to Omar’s Christ-like vision of a fundamental Islamic nation. Yaqoob would know. Where is Yaqoob? Pakistan.”

Billie was the first to take the stand. She was asked why her daughter “took up an interest at the age of 17 in learning Arabic or Farsi or Dari or any of those?” and whether she had ever heard her daughter make plans to meet with the Taliban. She was asked whether her daughter had ever been in trouble, and she told the old story of the eighth-grade food fight Reality had insisted not be on spaghetti day.

Over the course of the hearing, the prosecution pointedly used the phrase “not criminal, but … of interest.” It’s not criminal, but it is “of interest,” to know how to change a sim card. It’s not criminal, but it is “of interest,” to own “four phones, two laptops, and one tablet.” And then there was the fact of a woman’s traveling alone to Belize “by herself for only three days, including travel. Nothing criminal about that, Your Honor, but it seems odd.”

The prosecution cross-examined Reality’s stepfather; when they called her his stepdaughter, he corrected them: my daughter.

“You and your wife were largely unaware of what your daughter did in terms of her employment,” the prosecutor said.

“She carried a Top Secret security clearance.”

“Right. So you really didn’t know what it was—”

“They can’t discuss what they do.”

There was also the question of character, and here the prosecution made frequent reference to jailhouse calls between Reality and her sister, which, it turned out, had been recorded: There was the conversation about Orange Is the New Black. “This defendant has shown her intent and her plan to manipulate this court,” said Solari, “by playing a cute white girl with her cute little braids and perhaps shedding some tears.”

I’ve spoken to Billie about her daughter for hours at a time, and it’s only the memory of the bail hearing that brings her to tears. “They took her words,” says Billie, lifting her glasses, closing her eyes, pressing her fingertips to her brows, “and they twisted them around.”

This is perhaps the most surprising thing about the story of Airman Reality Winner, linguist, intelligence specialist, a woman who spent years of her life dropping in on conversations among people this country considers potential enemies: It did not occur to her, in a moment of crisis, that someone might be listening.

Since her June arrest, Reality’s access to the outside world has been severely circumscribed; she is only allowed to see people for a single hour on Saturday and Sunday mornings, and those people, friends and family, must be on a list of nine that she gives the jail in advance.

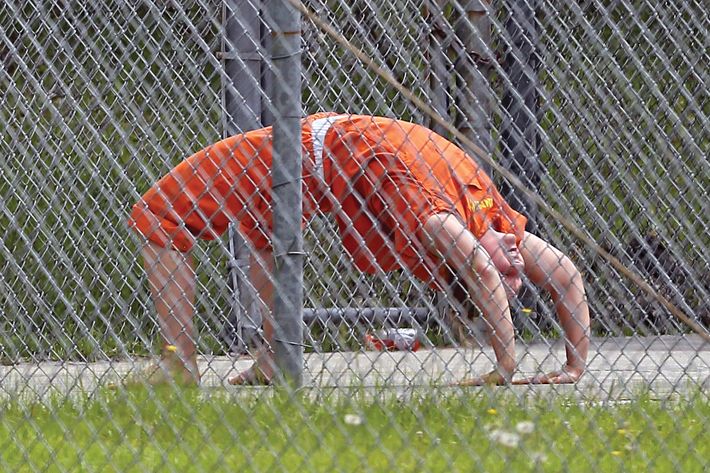

In September, in a letter that included a hand-drawn heart under the valediction “peace and love,” Reality agreed to add me to that list, and a few weeks later I flew to Atlanta and drove three hours to the small town where she is being held. At the town center of Lincolnton, Georgia, sits a monument to the Confederacy. Attached to the courthouse, described by the state tourism board as “in the neo-classical revival style” — behind it and not visible from the road, in what is best described as “riotproof institutional”— is a one-story brick box lined with wire fencing. This is the Lincoln County Detention Center, a decidedly strange place to hold a federal prisoner on national-security charges, where the first person to be charged under the Espionage Act during the Trump administration watches Breaking Bad with women doing time for methamphetamine abuse. The jail is attached to a fenced concrete platform topped with coiled barbed wire, which I recognized immediately because I had seen it in pictures of Reality published on TMZ under the headline “Reality Winner Still Working Out Behind Bars.”

In jail, Reality continues to be the kind of person who would order a boyfriend to read a particular number of books a week. She teaches yoga in the space between beds, frets about the low calorie intake of a pregnant inmate, asks her mother to contribute to the commissary funds of the others. She is teaching herself Latin from a textbook in order to read Ovid in the original; above her bunk, stuck to the wall with toothpaste, is a picture of Nelson Mandela. During Bible-study sessions, she asks so many challenging questions of the instructor that the others have begun to see her as a useful distraction; they can get some extra sleep while she takes up the teacher’s time. In letters to friends and family and to me, she throws side-eye to her captors. “I hope this finds its way to you expediently,” she writes, “—looks at the vague, yet menacing government agents—”

On the Saturday morning in October when I came to visit Reality, the day was bright and warm, but through a set of double doors, in the fluorescent-lit waiting room of the Lincoln Country Detention Center, weather ceased to exist. A guard behind glass took my license through a slot, checked it against Reality’s visitor list. She led me into a narrow room and disappeared.

Reality and I spoke between glass on thick black phones tied to the wall by silver cords. She smiled shyly and spoke in complete sentences aphoristic in their tidiness. She was disappointed because when she had asked on Friday to go outside to have her allotted 30 minutes on the concrete platform surrounded by electrified wire, she had been told no. There was no outside time on weekends, so she would have to wait until Monday to ask again for the privilege of seeing some natural light. Alone in the room, on a recorded line, we talked, for a few brief minutes, about Kingsville, life in captivity, her father.

“He never shied away from ideology,” she said of their post-9/11 conversations. “Even though we were 10, 12, he told us exactly what they believed.”

As she took me through his thinking, the guard who had let me in opened the door and began to watch us.

“I had a map of the world above my bed,” said Reality, “but I didn’t know that—”

“Are you a reporter?” asked the guard.

“What’s going on?” Reality said, snapped out of calm into anger.

Forced back into the waiting room, I pleaded with the guard, who never stopped, during our interaction, slowly shaking her head. To talk to Reality, I would have to talk to a sheriff, who was not available and would in any case refer me to the Feds, who would refer me to a byzantine and self-evidently impossible process for obtaining the state’s permission to interview her. That Reality clearly wanted to tell her story was not sufficient reason to let her. Moments after I left, she called her mother. “They’re silencing me,” she said.

If her case goes to trial as scheduled in March, it will be watched by a growing class of intelligence professionals burdened by knowledge of a surveillance state, its programs and excesses, its featureless physical structures. They will watch as Reality’s lawyers struggle to defend her, because she likely will not be able to argue that leaking evidence of Russian interference in an American election is in the interest of the American public. In recent Espionage Act cases, prosecutors have successfully argued that the intention of the leaker is irrelevant, as is the perceived or actual value of the leak to the public. Accused, Reality finds herself trapped in this strange logic of secrecy, in which her dutiful discretion with members of her family is taken to be evidence that her family cannot defend her character, and the only room in which her intentions do not matter is the one in which she is set to be tried.

I drove out of Lincolnton, not without relief, past the concrete block surrounded by wire in which Reality was hoping to be allowed, out of sight of the courthouse, into a warm autumn morning, the leaves turning, and past a lush lawn canopied by oak trees where a large family was preparing for some kind of party. There were tablecloths on the foldout tables. This seemed to me amazing, to be outside and having a party, to have thought of tablecloths. I was headed to Augusta to talk to Reality’s mother and see the house where Reality had been seized. I was headed toward Fort Gordon, where the Army is building another Cyber Command center, next to the one in which Reality worked, where receivers will suck more conversations from the air and more cleared linguists will translate them. I was headed to the Savannah River, and when I got there, I pulled off. On the banks of this river, I was aware, the state of Georgia had begun building a massive high-tech training center to support the NSA.

I didn’t want to see the river and think about satellites, just as I didn’t want to think about intimate conversations in Iran violated by linguists in Georgia, or sisterly banter on Facebook probed by prosecutors in Washington, so I thought about a story the family had told me, about a vacation to SeaWorld when Reality and Brittany were just girls. The Winners took in a show, watched sleek gray dolphins leap in unison, their sweet-sounding squeals elicited on command. Brittany was loving it. At which point her little sister — ever the explainer, ever the scold — declared that in captivity, the dolphins’ signals bounce crazily off the walls; their capacity for echolocation drives them mad. For Brittany, the show was ruined. It had been easier not to know what was hidden below the visible, beneath the bright surface of the cage.

*This article appears in the December 25, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.