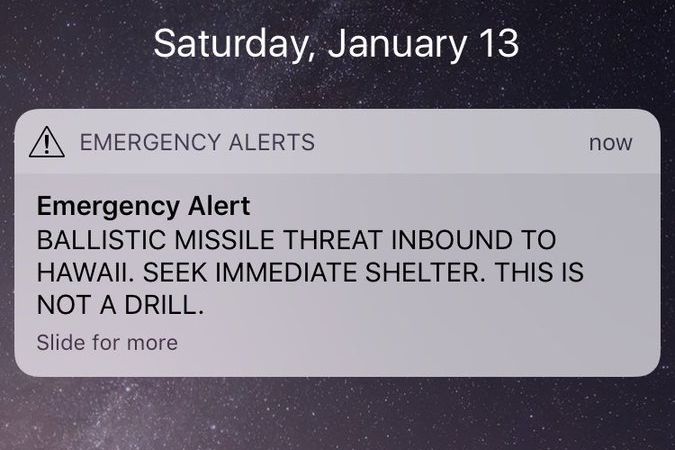

Hawaii’s efforts to prepare for the possibility of a nuclear attack from North Korea took a disastrous turn on Saturday morning when a state employee mistakenly triggered an alert warning Hawaiians that a ballistic missile was on its way, and instructing them to seek shelter. “This is not a drill,” the mobile-phone notification and automated television and radio announcements assured, causing widespread panic in the 38 minutes it took Hawaii authorities to send a follow-up message canceling the false alarm.

In light of the escalating tensions between the U.S. and North Korea, Hawaii has been testing and updating its Cold War–era missile-threat preparations since December, conducting monthly tests of air-raid sirens and working to educate the public about best practices in the unlikely event of an attack. On Saturday, countless Hawaiians experienced what that would actually be like, and the mishap exposed numerous flaws in the state’s emergency procedures, the public’s readiness, and the federal government’s response plans. It was also the worst failure of the already-flawed U.S. Wireless Emergency Alert system since it was adopted in 2012.

How It Happened

The mistake started while a shift change was under way on Saturday morning in the bunker headquarters of the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency (HEMA). During a routine test of the state’s emergency and wireless-emergency alert systems, a state employee selected “missile alert” instead of “test missile alert” from a drop-down menu in the agency’s alert-system software, then confirmed his incorrect selection with another click.

Because of that human error, at roughly 8:07 a.m. local time, the false ballistic-missile alert was sent out to mobile phones across the state, and a longer version of the same pre-written warning was automatically broadcast on the state’s television and radio stations. No outdoor sirens were triggered by the alert, as they are part of a separate system, but some military bases voluntarily activated their sirens in response to the alarm anyway.

Once the alert reached the public, widespread panic followed throughout the state as terrified residents and tourists rushed to take shelter, contact their loved ones, and obtain more information about the impending attack. While many people thought they were about to die, no deaths or injuries have been reported as a result of the screwup.

Staff at HEMA didn’t realize the alert had gone out until other officials called them requesting more information about the threat, and an agency spokesperson said on Saturday that the employee who made the error learned of his mistake only after receiving the missile warning on his own phone. Three minutes after the alert was sent, HEMA confirmed with U.S. Pacific Command that there had been no launch and informed the police. Three minutes after that, the agency issued a cancellation of the alert so it would stop being rebroadcast, but it wasn’t until 8:20 a.m. that HEMA posted the cancellation on their Facebook page and Twitter account. Due to poor contingency planning, it then took them another 25 minutes to be able send a new notification out to people’s phones acknowledging the false alarm, which the agency finally did at 8:45 a.m.

On Saturday, Hawaii governor David Ige and HEMA administrator Vern Miyagi both apologized for the panic, anguish, and anger caused by the false alarm, and they vowed to change the system to prevent such mistakes in the future.

The employee responsible for the error, who has not been identified, has reportedly been reassigned, but not fired. Miyagi said on Saturday that the staffer “feels terrible” about the mistake.

A few state-level investigations are already under way, and tests of Hawaii’s alert system have been suspended until procedures can be put in place to prevent future mishaps. The FCC has also launched an investigation into the incident, and it blasted Hawaii officials on Sunday for the “unacceptable” error, concluding that the state “did not have reasonable safeguards or process controls in place to prevent the transmission of a false alert.” It also urged federal, state, and local authorities to immediately review their emergency-alert procedures to prevent similar mishaps.

What Should Have Happened

In this case, nothing: The agency should have conducted its daily test, not fired off the false alarm, and Hawaiians could have gone about their Saturday morning uninterrupted. But if North Korea had fired an intercontinental ballistic missile at Hawaii, it would have first been detected by the U.S. Pacific Command, which would have instructed the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency to warn the islands using the state’s alert system, which consists of outdoor sirens, mobile-phone notifications, and emergency announcements on television and radio. Subtracting the time it would take to detect the missile launch, alert state officials, and then warn the public, Hawaiians would have 12 to 20 minutes to seek shelter before the missile traveled the more than 4,600 miles from North Korea.

HEMA officials believe that 90 percent of the state’s 1.4 million residents would probably survive the initial blast, though the state has few official fallout shelters to ensure residents are protected during the attack. Regardless, Hawaiians have been advised to remain inside for as long as 14 days following a nuclear strike, and to listen to AM/FM radio stations for additional announcements from officials.

What Else Went Wrong

Beyond the state employee’s initial screwup with the drop-down menu, the false alarm exposed a variety of problems with how the state initiates and responds to such alerts. First and foremost, the fact that one employee alone had the power to send an emergency message to more than a million people with no additional checks and balances was a disaster waiting to happen. HEMA designed the system that way to cut down on the time it would take to send a message, but the agency has announced that triggering the alerts will be a two-person job from now on, with one employee selecting the alert and another employee confirming it. There are also likely to be questions about improving the interface design of the software to prevent future mistakes, but that is often easier said than done when it comes to the software used for a government system.

The other primary problem was how long it took to issue the various corrections following the alert, and the fact that no procedures were in place to handle such an event. It is not yet clear why it took the agency, or anyone else in the state government, 13 minutes to send out some kind of public message canceling the alarm. It’s also not clear if state officials contacted local media stations to get help notifying the public about the mistake, and if they didn’t, why. For many, Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard’s tweet debunking the threat at 8:19 a.m. was the first correction anyone saw. Governor Ige’s Twitter account didn’t flag the mistake until 8:24 a.m.

The 38-minute delay in issuing a followup alert was due to the fact that without a procedure for sending corrections in place, HEMA had to craft a new manual message — as opposed to preapproved, pre-written ones it would automatically use for most emergency alerts — and they then had to get authorization to send the correction from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which oversees the national alert system. It’s not yet clear why that process took as long as it did.

Other state and local authorities had problems too. Stunned police departments throughout the state struggled to respond to the panic, initially to help people find shelter, and later to help notify the public that everything was okay. Honolulu’s 911 system was quickly overwhelmed with more than 5,000 calls, only half of which went through, and some police officers drove around populated areas using their vehicle PA systems to announce the all clear. In many other cases, it was up to neighbors and family members’ word-of-mouth campaigns to spread news of the false alarm.

Furthermore, while the notification could have conceivably gone out to every mobile phone in the state, many never received it and officials aren’t sure why. Some people didn’t receive the original alert but did receive the correction, so it’s possible the quick cancellation of the false alarm prevented some phones from ever receiving the message. But it also seems likely that if the threat had been real, the system still wouldn’t have worked as intended.

The Public’s Response Was a Problem Too

Looking at the reports of how people reacted to the warning, it’s clear that very few were prepared for such a crisis. Many Hawaiians may have already thought through what to do in the event of a tsunami or hurricane, but not a nuclear attack. Those who received the warning on Saturday were forced to immediately answer some important questions: Where was the safest, nearest place to shelter, and did they have enough time to get there? Where was their family and could they reach them? What supplies did they need? And what should parents tell their children?

Indeed, some of the most harrowing accounts of reactions to the alert are about parents trying to calm young children who were asking if they were about to die. People ran out of and into buildings. Some hotel guests were herded into basements. Hawaiians hid in bathrooms while filling their tubs with water, or just sheltered in place behind big furniture. On the roads, there were reports of drivers parking inside tunnels, or running red lights, driving on the shoulder, and simply abandoning their cars in search of shelter. At Honolulu Airport, at least some airline and TSA personnel reportedly had no answers as to what passengers should do following the alert, and it seems no public announcements were made by airport officials.

Some people have also said that they just assumed the worst and stayed where they were, expecting to die. Many people sent texts or made panicked calls to family members to tell them that they loved them.

Saturday’s false alarm provided a massive test of Hawaiians’ readiness for a nuclear attack, and it didn’t go well. The only upside is that researchers, social scientists, and state officials now have a lot of new data to learn from to create better plans for future crises.

The Trump Administration

While Hawaii’s Emergency Management Agency was responsible for the mistake, that doesn’t mean that the episode didn’t expose failures at the federal level as well. Politico reports that White House aides were left “scrambling” to respond to the false alarm on Saturday, since President Trump’s cabinet hadn’t yet tested any formal plans for responding to a missile attack on the U.S. — despite the fact that the Trump administration has presided over the worst nuclear crisis the U.S. has faced since the Cold War. Before becoming White House chief of staff, former Department of Homeland Security chief John Kelly had planned to conduct such an exercise, but it wasn’t carried out after he left the agency. A deputy-level exercise was run on December 19, but not with cabinet secretaries. “Without a principals-level exercise, we shouldn’t have any confidence that the cabinet would know what to do in an attack scenario,” a senior administration official told Politico.

It’s also not yet clear if the federal government, which obviously has its own access to the Wireless Emergency Alerts system, could have sent their own correction message to Hawaiians faster than state authorities did. For its part, U.S. Pacific Command was apparently hesitant to issue its own alerts without coordinating with Hawaii officials, fearing the messages would only exacerbate the confusion.

And Trump Kept Golfing

It being a Saturday, President Trump was golfing at his course in West Palm Beach, Florida, at the time of the Hawaii alert and its immediate aftermath, eventually returning to his Mar-a-Lago residence around the time Hawaiians found out the alert was a mistake. It’s not clear if he was informed of the alert while he was golfing or not, especially since there wasn’t an actual missile launch to worry about. Trump’s National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster later briefed the president about the incident, according to an administration official. The White House subsequently released a statement that seemed to indicate that they considered it Hawaii’s problem. “The president has been briefed on the state of Hawaii’s emergency management exercise,” it read. “This was purely a state exercise.”

Trump, whose public responses to tragedies within the U.S. are inconsistent at best, said nothing about the scare on Saturday night, though he did eventually tweet about “fake news” again. Talking with reporters on Sunday, Trump said that the Hawaii false alarm “was a state thing, but we are going to now get involved with them,” adding that his administration hoped the mistake wouldn’t happen again.

The president then seemed to reference the crisis with North Korea in relation to Hawaiians’ newfound fear of nuclear war. “Part of it is people are on edge, but maybe eventually we will solve the problem so they won’t have to be so on edge,” explained Trump, who recently boasted that he had a bigger and more powerful nuclear button than Kim Jong-un, leading to a surge of Americans buying anti-radiation pills. President Trump has also sought to expand America’s nuclear arsenal and to cancel or weaken the U.S. nuclear deal with Iran, and he has casually threatened to annihilate North Korea, which used to be the only country in the world with a leader prone to such hyperbolic outbursts about nuclear war.

As the New York Times’ Max Fisher and others have pointed out since Hawaii’s crisis on Saturday, nuclear standoffs are historically prone to dangerous errors and misunderstandings, and it’s worth considering what could have happened if North Korea had concluded that Hawaii’s false alarm was some kind of U.S. deception meant as a prelude to war.

America’s Flawed Emergency Alert System

The false alarm in Hawaii was also the latest and most dramatic example of the problems with the U.S. Emergency Alert System, particularly its newest, yet already-outdated tool, the Wireless Emergency Alerts system. Wireless emergency alerts, which appear as notifications on mobile phones, are supported by every major U.S. mobile carrier. WEAs include three types: Amber Alerts for missing children; alerts about imminent threats to the public’s safety; and alerts issued directly by the president. Federal, state, and local authorities can issue the first two kinds of alerts, assuming the agencies have been granted that authority by FEMA, which manages the system. But while alerts sent to mobile phones are undoubtedly the easiest way to reach the largest percentage of the American public in this day and age, the system has numerous flaws and the escalating calls for improving the system will only get louder after Saturday’s fiasco in Hawaii.

Most of the criticism of the WEA system centers on the fact that the wireless alerts are more of a blunt instrument than a precise tool. For instance, it is difficult to target specific localized areas with the alerts. Emergency officials in California recently chose to avoid the system when it wanted to notify residents about the deadly threat posed by last month’s devastating wildfires, as the officials were afraid of causing mass panic outside the danger zone. The alerts are also, for now, only available in English, and are limited to 90 plain-text characters with no links, phone numbers, or images allowed.

The FCC has already been tasked with updating the system. Current FCC commissioner Ajit Pai recently announced a proposal to improve the geotargeting of WEAs. But the FCC already tried to overhaul the WEA system in late 2016, requiring participating wireless companies to allow better geotargeting and 360-character multi-language alerts that could include hyperlinks, telephone numbers, and images. The telecom industry responded by resisting the changes and pushing for delays, citing logistical, training, and network concerns. Some in the industry have also sought to delay regulations that require telecom companies to enable testing for local- and state-level authorities.

The wireless alert system is actually a part of a larger system called the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System, or IPAWS. The whole system, which also includes television and radio alerts, is accessed by authorities using a web interface that serves up cached messages related to different emergency situations. The problem exposed by the Hawaii incident, according to retired admiral David Simpson, a former chief of the FCC’s Public Safety and Homeland Security Bureau, is that states, unlike the Department of Defense, don’t have a good firewall between their test environments and their live environments. Furthermore, as this former emergency-services dispatcher points out:

And such state- or local-level EAS systems, built to run on outdated equipment, could also be prone to technical failures or hacking, as Ankit Panda worries in The Atlantic:

In September 2017, U.S. military personnel and their families in South Korea received false mobile alerts instructing them to evacuate the Korean Peninsula — an alert that would be among the most-reliable indicators of impending U.S. military action against North Korea. U.S. forces in South Korea later clarified that they hadn’t sent the alert, and U.S. counterintelligence opened an investigation. That investigation is ongoing.

Issuing a false alert of an impending ballistic-missile strike through a legitimate EAS may be among the most pernicious forms of “fake news.” At a time when state and non-state actors alike are resorting to disinformation operations, it’s all the more important for the U.S. government to ensure the inviolability of critical communication systems like the EAS.

Indeed, one of the most important reasons that what happened in Hawaii can’t happen again is that false alarms erode the public’s trust in this already-flawed system. New Yorkers will remember how some residents ignored the evacuation orders for the deadly Superstorm Sandy because the year before, the mandatory evacuations ordered for Hurricane Irene turned out to be unnecessary. Critics are also concerned about the inflation of mobile-phone notifications, especially since most emergency alerts can be disabled in a phone’s settings.

A populace that thinks the government is wasting their time or teasing near-death experiences for the whole family is not one public officials will be able reach when it really counts. Hawaii’s alert may have been a false alarm, but it was still a good warning.