Donald Trump’s immigration agenda has been widely described as populist and nationalist — a set of policies that puts the needs of Americans first, and multinational firms second. During his campaign, the Republican nominee blasted the Establishment consensus on immigration reform as “nothing more than a giveaway to the corporate patrons who run both parties,” and boasted that he had developed his proposals with the aid of “the top immigration experts … who represent workers, not corporations.”

And it’s true that many of the president’s immigration policies have attracted the ire of corporate America. Silicon Valley has nothing to gain from a travel ban that bars Iran’s vast reservoir of engineers from visiting the United States; discouraging illegal immigration doesn’t grow Big Agriculture’s profit margins.

But one of the immigration reforms that Trump has championed most vigorously in recent months — switching from a family-reunification (or “chain migration”) system of immigration to a “merit-based” one — runs counter to this paradigm.

Under a merit-based system, a team of elite economic experts analyzes what kinds of skilled laborers corporate America needs more of (and/or would like to pay lower wages to), and then develops admissions criteria to select for such workers. Under a family-reunification system, by contrast, ordinary Americans select immigrants on the basis of kinship, and the needs of their families.

It is hard to see how the first approach is more “populist” or “nationalist” than the second. If Trump’s critique of America’s status quo immigration policy is that it is bloodlessly technocratic — privileging economic growth over the nation’s social fabric — then redesigning that system to better fit the needs of corporations, at the expense of American families, would seem to make matters worse.

In fact, in an earlier era, conservatives understood family reunification as an anti-globalist alternative to skills-based immigration. During the debate over the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, it was liberals who pushed for a merit-based approach. At the time, American immigration operated on a quota-based system that severely restricted newcomers from Africa and Eastern and Southern Europe, while all but banning immigrants from Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East.

“In establishing preferences, a nation that was built by the immigrants of all lands can ask those who now seek admission: ‘What can you do for our country?’” Lyndon Johnson told Congress, advocating for a system that privileged skills over national origin. “But we should not be asking: ‘In what country were you born?’”

Lacking the votes to preserve the quota system, conservatives saw family reunification as the second-best option. As Nick Miroff recently explained in the Washington Post:

Conservatives, especially the Southern Democrats who opposed Johnson’s civil rights legislation and Great Society agenda, were set against the immigration overhaul. But Rep. Michael Feighan (D-Ohio), a longtime immigration hard-liner, devised the family unification model as a compromise to preserve America’s ethnic status quo.

“The idea was that you wouldn’t get many Asians or Africans coming in because they didn’t have relatives here,” said Tom Gjelten, an NPR correspondent and author of “A Nation of Nations: A Great American Immigration Story.”

This proved to be a significant miscalculation. With the quota system vanquished, longtime Asian, Latin American, and African U.S. citizens could finally sponsor the immigration of their extended family members from overseas — who could then, in turn, sponsor the immigration of their extended family members. The result was a demographic revolution. In 1950, barely 10 percent of the American population was nonwhite; by 2014, that figure was 38 percent.

But the Trump administration insists (most of the time, anyway) that its opposition to family-based immigration isn’t motivated by the policy’s demographic implications. The president’s immigration agenda is nationalist — not white nationalist. As Trump explained in his first State of the Union address, the populist “rebellion” that propelled his candidacy “started as a quiet protest, spoken by families of all colors and creeds … all united by one very simple, but crucial demand: that America must put its own citizens first.”

And yet, if one believes that recently naturalized citizens — regardless of color or creed — are fully and truly American, then it’s difficult to understand how ending “chain migration” is putting all American citizens first. After all, the people sponsoring extended family members to come to the U.S. are American citizens.

Of course, one could argue that merit-based immigration is better for economic growth, and thus, that such a system maximizes the well-being of all citizens. But this rationale doesn’t fit the president’s actual policy proposal. Trump’s preferred legislation for establishing a merit-based system is the RAISE Act, which simultaneously cuts all legal immigration in half — a measure that would dramatically reduce GDP and job creation.

It’s true that such a reform would likely have a modest, positive impact on native-born wages. But this would come at the cost of a much higher deficit and much smaller workforce, which together would pose a significant threat to the sustainability of Social Security and Medicare. Furthermore, there is little evidence that this administration is committed to increasing wages — let alone, at the expense of economic growth. The president’s policies on labor rights, unionization, and the minimum wage — combined with his decision to nominate a a Federal Reserve governor who has argued that an unemployment rate above 7 percent is preferable to an inflation rate over 2 percent — all suggest that wage growth is not actually a priority for this White House.

A seperate (ostensibly) race-neutral argument that Trump has repeatedly made against “chain migration” is that it poses a threat to national security.

If it were true that family-based immigration substantially increased the incidence of terrorism in the U.S., then there might be an argument that ending such a policy would be a net benefit to all American citizens. But there’s virtually no evidence for that claim. And, as with growing wages, the Trump administration’s concern with minimizing acts of mass violence against American civilians is conspicuously absent outside of the immigration context. The White House offered essentially no policy response to the deadliest mass shooting in American history.

But even if Trump did have a coherent policy argument for his version of merit-based immigration, his rhetoric would nonetheless suggest that not all Americans citizens are equally American. The president and his advisers do not argue that, while “chain migration” benefits some American citizens, ending it is in the best interests of the nation as a whole. Rather, they relentlessly frame the policy debate as a conflict between Americans and foreigners. This is reflected in the very definition of “chain migration” that the White House provides on its official website:

The process by which foreign nationals permanently resettle within the U.S. and subsequently bring over their foreign relatives, who then have the opportunity to bring over their foreign relatives, and so on until entire extended families are resettled in the country.” [my emphasis]

By the time an immigrant to the United States is sponsoring the visa application of an extended family member, she is an American citizen. The White House could have written that “chain migration” was “the process by which American citizens bring over their foreign relatives, etc. …” Instead, it portrayed those who benefit from the current policy as “foreign nationals” who have “permanently resettle[d] within the U.S.” They aren’t Americans who wish to be reunited with their loved ones overseas, but foreigners abetting the interests of other foreigners.

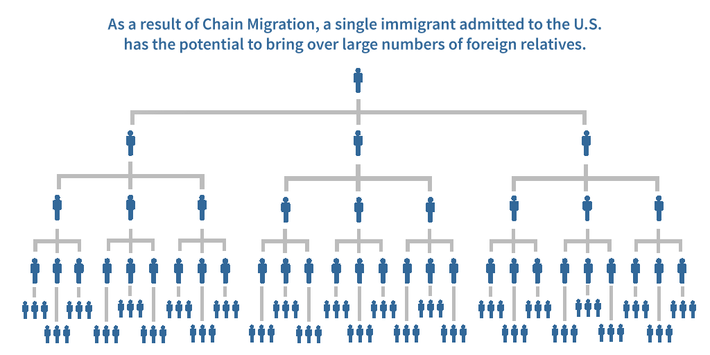

This idea is underscored by the administration’s visual depiction of chain migration, in a slide on its website.

Here, the American citizens sponsoring their relatives’ immigration are depicted as agents of a foreign invasion, or a rapidly replicating virus.

In 2015, Jeff Sessions — by all accounts, one of the primary influences on Trump’s immigration agenda — offered unqualified praise for the 1924 Immigration Act during a radio interview. Sessions argued that the legislation — which was so innovatively racist and anti-Semitic, the Nazis modeled much of the Nuremberg Laws on its example — helped create “the solid middle class of America, with assimilated immigrants, and it was good for America.” He further argued that the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act changed America in ways that its authors never intended, and that this mistake was in urgent need of redress.

Michael Anton, a senior White House national security adviser, wrote in 2016 that “the ceaseless importation of Third World foreigners with no tradition of, taste for, or experience in liberty” was making our nation “less Republican, less republican, and less traditionally American with every cycle.”

In recent weeks, the president has reportedly objected to immigration from Africa, on the grounds that Nigerians live in huts, and that most of the continent is a “shithole” (or, perhaps, a “shithouse”). He has also reportedly argued that America doesn’t need any more Haitians, who “all have AIDS.” Meanwhile, his administration revoked the legal status of 200,000 Salvadorans who had been in the United States for 15 years — suggesting that, in this administration’s view, spending more than a decade as a legal resident of the U.S. does not make one American enough to merit special eligibility for a green card. Instead of legalizing longtime American residents from Haiti, El Salvador, or Africa, Trump expressed a desire to take in more people from Norway.

For most of American history, the biggest point of tension in our nation’s immigration debate concerned whether or not the rising tide of newcomers was threatening our country’s racial character – and thus, the political freedom and personal security of its white citizens. In the decades since 1965, elite opinion makers have rendered this anxiety verboten. But it did not disappear.

Thus, Trump’s position on “chain migration” is only populist, to the extent that his arguments for it give voice to a worldview that elites have genuinely suppressed; and it is only nationalist, to the extent that the true American nation has an immutable color and creed.