In 1995, National Rifle Association president Wayne LaPierre signed his name to a fundraising letter referring to Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms agents as “jack-booted government thugs.” The implicit association of American federal law enforcement with fascists provoked a furor. Former president George H. W. Bush publicly resigned his NRA membership in protest; LaPierre had to apologize.

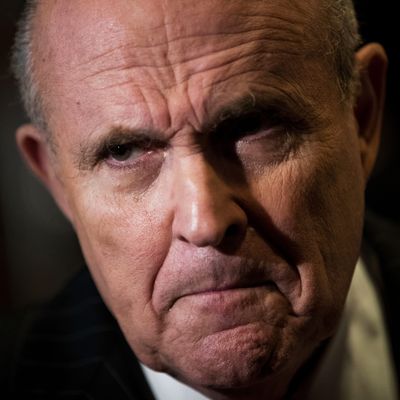

Last night, in the midst of a long, deeply incriminating interview, Rudy Giuliani called FBI agents “stormtroopers.” Here was the president’s lawyer, not an outside lobbyist, comparing federal law enforcement to Nazis directly, rather than indirectly. The Washington Post’s account of Giuliani’s interview noted the remark in a single sentence, in the 30th paragraph of its story. The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Politico accounts of Giuliani’s interview did not even mention the stormtrooper remark at all.

No doubt the flurry of hair-on-fire legal jeopardy unleashed by Giuliani’s remarks helped bury the newsworthiness of his stormtrooper line. Still, the casualness with which the line was uttered and received does indicate something important about the way Republican thinking about law enforcement has evolved. The party’s respect for the rule of law is disintegrating before our eyes, and in its place is forming a Trumpian conviction that the law must be an instrument of reactionary power.

None of the insults lobbed at the FBI by Giuliani should be confused with the long-standing, principled critique of law enforcement. Civil libertarians have spent decades articulating objections to the power of law enforcement and defending them regardless of whether they happened to benefit the right or the left. (The ACLU is famous for its commitment to defend civil liberties for the far right.) Substantial evidence has shown pervasive racial bias in law enforcement.

But conservatives are not arguing for civil liberties in the abstract, or promoting a generalized policy of more lenient treatment of criminal suspects. Indeed, in the same interview, Giuliani called for James Comey to be prosecuted and Hillary Clinton to be thrown in prison, beliefs that, in the Trump era, have become almost banal. Republicans simultaneously advocate total impunity for their presidency from the law coupled with harsh and even extra-legal punishments for their enemies.

The potential for abuse in turning law enforcement into a weapon of the party that controls government is so terrifying that any democracy has to limit it. For decades, federal law enforcement has observed a series of norms, codified after Watergate, designed to wall it off from partisan considerations. The system hasn’t worked perfectly — it broke down in 2016, when James Comey violated FBI policy and announced one of the candidates was under federal investigation. Comey was attempting to placate Republican demands that the Bureau put more pressure on Clinton, and — assuming she would win — tried to head off postelection recriminations. It was a disastrous miscalculation. But many leading Democrats afforded him some measure of absolution for his error because they respected the norm he was attempting, however clumsily, to defend.

Republicans are now engaged in a concerted effort to break down these protections altogether. Trump and his allies in Congress have repeatedly demanded that the Department of Justice ramp up their investigation of Trump’s opponents and ease up or stop the investigation of Trump’s campaign collusion with Russia. Republicans in Congress have made a series of demands that Rod Rosenstein, the acting attorney general, turn over a wide array of documents related to the Russia probe. The Department of Justice has customarily walled off active investigations from congressional involvement, but Rosenstein (like Comey) has been trying to appease Republicans by giving them unusual access to his evidence.

Rosenstein appears to have reached a limit. The New York Times reported yesterday that Rosenstein and some FBI officials “have come to suspect that some lawmakers were using their oversight authority to gain intelligence about that investigation so that it could be shared with the White House.” The Republican document-demanding game is that they either force Rosenstein to compromise the investigation, letting them inside the prosecution so they can help Trump undermine it, or else he refuses their demands, giving them a pretext to fire him and install a more pliable figure. Rosenstein publicly declared the other day the game was up and he wasn’t going to be extorted any more.

The Wall Street Journal, which has served as a reliable mouthpiece for Trump’s legal defense, defends Congress’s right to take control of the investigation. “Congress is acting through its committees as a separate and co-equal branch of government—the branch that funds Justice and has the right and obligation to exercise oversight,” it editorializes. Rather than denying Rosenstein’s charge that his department is being extorted, the editorial confirms it, treating him like a cowering store owner who hasn’t quite got the message. “We don’t want to see Mr. Rosenstein fired or impeached,” the Journal concludes, “but he and the FBI need to recognize Congress’s constitutional authority.” Nice Department you got there, Rosenstein. We’d hate to see something happen to it.

Earlier this week, Vice-President Mike Pence went out of his way to honor former Arizona sheriff Joe Arpaio. The case of Arpaio epitomizes the cutting-edge Republican philosophy about the rule of law. Arpaio has devoted his career to running roughshod over the law, including defying court orders, in order to intimidate immigrant communities who may or may not have run afoul of immigration law. The veneration of Arpaio, including Trump’s pardon of him, expresses their simultaneous belief in the law as something to applied with unrestrained brutality in their own hands, but that can be ignored altogether when they run afoul of it.

The duality of thought is the key to understanding it. Just as Giuliani can call the famously straight-laced Comey “perverted” in the very same interview he casually conceded that his own client habitually pays hush money to porn stars, Republicans can both fear the law as an instrument of terror while coveting it for the same purpose. This duality is how they can toggle between demanding ruthless authoritarian power and then, when describing their own legal predicament, squealing like the most unhinged anti-government radicals, comparing the FBI to Nazis. Trump holds this view with long-standing fervor, and has always combined a, shall we say, casual approach to legal scruples with demands for merciless law enforcement against the other (from Hillary Clinton to the Central Park Five) without any cognitive dissonance.

But Trump is not sui generis; his authoritarian impulses merely represent a more extreme iteration of a growing impulse on the right. At some point, the power of Trump’s government will either break the rule of law, or be broken by it.