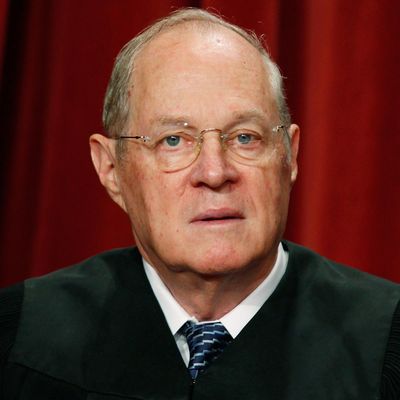

Just a day before he announced his retirement from the Supreme Court, Justice Anthony Kennedy released two back-to-back opinions, neither dispositive to the cases at hand, but each with a different message for the American public. Call them a valedictory, if you will.

In one decision, which invalidated a California law that required pro-life counseling centers to tell women that the state provides abortion-related services at little to no cost, Kennedy offered a rousing defense of the First Amendment — all but suggesting that his home state was flirting with totalitarianism and an all-out assault on the freedoms that the Founders sought to protect. “Governments must not be allowed to force persons to express a message contrary to their deepest convictions,” Kennedy wrote. “Freedom of speech secures freedom of thought and belief.”

In the other ruling, which upheld Donald Trump’s authority to ban Muslims from the United States, even as he denigrates their very existence, Kennedy was a different person. Sounding as docile and harmless as a dove, he offered a tepid rebuke of the president — one that wouldn’t even dare call him out by name. There, his defense of the First Amendment was muted at best. “It is an urgent necessity that officials adhere to these constitutional guarantees and mandates in all their actions, even in the sphere of foreign affairs,” he wrote. “An anxious world must know that our Government remains committed always to the liberties the Constitution seeks to preserve and protect, so that freedom extends outward, and lasts.”

At a time when an anxious world is as stable as Trump’s state of mind on any given day, and the Constitution seems on the brink, Kennedy’s decision to step down from the nation’s highest court is as puzzling as those two conflicting opinions, which serve as reminders of the conflicting jurisprudence he leaves behind — one that held up the human dignity of gays and lesbians, was deeply respectful of religion and states’ rights, and often sent mixed signals about the level of deference the government was due.

There’ll be little time for reflecting on any of that in the coming days. Kennedy’s looming resignation is less a testament to three decades of committed judicial service, which no one can really call into question, than a recognition that this president just may be like any other chief executive that he’s served under. From Ronald Reagan, who nominated him after a bruising confirmation fight at the height of the abortion wars of the late 1980s, to Barack Obama, under whom he acknowledged that same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marry and that abortion rights and affirmative action should remain firmly rooted in our constitutional canon.

None of those things is safe under Trump — who campaigned on appointing judges who are committed to overturning Roe v. Wade, whose Justice Department is downright hostile to civil rights and liberties, and who has displayed nothing but disdain for women’s health, religious minorities, immigrants, law-enforcement agencies, and government institutions, to say nothing of the rule of law. Just as courts have served as a limited safeguard against Trump’s worst excesses, Kennedy, it seems, would rather watch it all burn from the sidelines.

This tacit surrender to Trump and all he represents — and his willingness to allow his name and legacy to be brandished in the coming battle over his replacement — says more about the senior justice than anyone else. He may be the Supreme Court’s enduring center of gravity. But in the term that just wrapped up today, he was, more than anything, dead weight. Not a moderating force. Not a guardian of liberty. Not a champion for equality or those the government seeks to trample. He was just there, offering a few platitudes about respect for gays and lesbians in Masterpiece Cakeshop, but nonetheless willing to side with a Christian baker who, in his view, had been the target of Evangelical hostility.

That he was unwilling to raise his voice with equal force for Muslims here or abroad in Trump v. Hawaii — or for voting rights, labor unions, or even against the surveillance state in the digital age, all cases where he voted squarely with conservatives during the last term — betrayed a certain tiredness and lack of enthusiasm for the very principles of equality and liberty that for 30 years we believed he held dear. Maybe he still does. But when you can’t even cite Romer v. Evans, your first gay-rights landmark, to affirm the worth of religious minorities in the travel-ban ruling, maybe it’s time to hang it up and call it a day.

For Trump and the conservative legal movement, which never liked Kennedy much anyway, his surrender is a coup. “Liberty finds no refuge in a jurisprudence of doubt,” one of the justice’s unforgettable lines in a case that Republicans rue to this day, may just become a self-fulfilling prophecy, as one of the worst presidents in modern history now sets out to erase much of what he accomplished in the law.